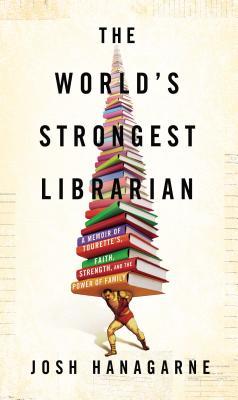

Libraries have shaped and linked all the disparate threads of my life. The books. The weights. The tics. The harm I've caused myself and others. Even the very fact that I'm alive. How I handle my Tourette's. Everything I know about my identity can be traced back to the boy whose parents took him to a library in New Mexico before he was born.In The World's Strongest Librarian, author Josh Hanagarne outlines the many challenges that he has faced throughout his life – extreme Tourette's, challenges to his faith in the Mormon church in which he was raised, infertility struggles with his wife – and also the bedrocks that saved him from complete despair – his supportive family, books, and weight lifting. At six-feet-seven, two hundred and sixty pounds – with a background in kettle bell training and participation in at least one Highland Games – Hanagarne likely is the strongest librarian in the world, but he's not exactly the world's best memoirist.

Each chapter in this book follows the same structure: A list of the subjects that will be dealt with (by Dewey Decimal number); a madcap story from Hanagarne's job as a librarian at the Salt Lake City Public Library (preventing the homeless from watching porn on the computers, asking security to help a schizophrenic track down the source of the voices in his head, chastising a mother who let her children rip up books – and then watching those children get slapped); followed by a related section of his own biography. In the final chapters, as Hanagarne has had time to reflect on the lessons he has learned in life, he includes long platitudes about the value of faith and family and the enduring necessity for public libraries (shocking stuff, right?) For a person who appears to have an inspirational story to tell, the book that Hanagarne wrote here just feels so flimsy and surface; there's very little blood in these bones.

I really liked Hanagarne's description of his Tourette's and how it has impacted his life since it first appeared when he was around six. From the shunning of his classmates, to the impact it had on his Mission at 18, to the increasingly violent nature of his tics, Hanagarne certainly taught me a lot about the disorder. What he didn't do was to engage me emotionally with this part of his struggle – he shared a lot of facts without sharing his reactions – and personifying the symptoms as “a visit from Misty” (for Miss Tourette) served to further distance me as a reader; not only did I find that too cutesy, but how am I to empathise with a struggle that the author places outside of himself?

I also really liked Hanagarne's description of Mormon faith and life – without proselytising, he was able to show what a supportive and loving community he came from. I appreciated the closeness of his family (I loved that when their father told the four kids that they could each bring a friend on a fishing trip, they chose each other) but I wondered where his parents and siblings were when he was at his lowest points – they aren't really characters in Hanagarne's life story unless he wants to mention how much he loves them. When he eventually realises that he can't accept the teachings of the church on faith alone, his mother, wife and bishop are all loving and accepting of his decision, so what might have been an interesting bit of narrative tension, fizzles out.

I was really interested in Hanagarne's involvement with Dragon Door and kettle bell training and how that led him to Adam T. Glass:

Adam is a former air force tech sergeant, an expert in hand-to-hand combat, and the sort of hard-ass who describes poor haircuts as “a lack of personal excellence”, even though his hair is currently poufy and awful and makes him look like a Dragon Ball Z character.That Glass – a man with autism – could coach Hanagarne into a mastery over Tourette's was, finally, the sort of overt triumph over adversity that makes an engaging memoir (and especially when Glass is such a fascinating character himself), but then Misty reappears and the whole kettle bell thing becomes just a weird hobby.

I admire Hanagarne – you can't help wondering about the kind of person who becomes a librarian because he can't remain still or quiet – but this wasn't a great book. I do see that The World's Strongest Librarian has plenty of rave reviews, so this must fill the bill for plenty of others, just not for me.

A good library’s existence is a potential step forward for a community. If hate and fear have ignorance at their core, maybe the library can curb their effects, if only by offering ideas and neutrality. It’s a safe place to explore, to meet with other minds, to touch other centuries, religions, races, and learn what you truly think about the world.

Hanagarne makes many platitudinous statements about the importance of libraries, even in these changing times; even if people aren't interested in books, he wants everyone to acknowledge that A community that doesn't think it needs a library isn't a community for whom a library is irrelevant. It's a community that's ill. I don't know how I feel about that -- certainly libraries were essential for the democratization of knowledge once upon a time, but now that we all have the sum total of human learning on our smart phones, is a physical library more important than any other community center? And I say that as someone who uses the physical library weekly.

Here's my first library memory: It was summertime in St John and my little brother and I walked to the library with a wagon. We were maybe 6 and 4? Having very few books at home, I loaded that wagon up with everything Kyler and I wanted, but when we went to check them out, the librarian said there was a limit to how many we could have. I always had confrontation-with-adults issues, and I have no memory of this librarian being nasty to me about this, but I was obviously upset about the "confrontation" when I got home. My mother, upon hearing that a librarian had dared to censor her daughter's reading material (my mother, raised Catholic, was hyper sensitive to censorship and the hated Indexing of books) either called up the library or hotfooted it down there to make sure everyone knew that I had her permission to take out anything I wanted, that information was not to be shielded from me, etc. I have no idea how this conversation actually went but it became one of her standard stories of my childhood: I came home upset because a librarian wouldn't let me take out some books I was interested in and she fought the system for me. This is a very heroic story for her, but here's the simple truth: I don't remember my mother ever taking us to the library (but I suppose she must have at least once if I had my own card at 6 or so). Heroic would have been taking me there regularly so I wouldn't think I needed to bring a wagon.

And apparently, my mother was a frequent user of this library. Another of her favourite stories was how she would love it when we kids would ask her a question she couldn't answer because then she would go to the library -- sometimes for a whole day -- and research until she had our answers. I also have no recollection of ever asking my mother a question that she came back with an answer for at some later time. And that might all be a failure of my own memory; I'm sure my own kids won't remember all of my heroic motherhood efforts.

After we moved to Stouffville, I honestly don't remember if I got a library card and don't remember taking out books, but by then, we could borrow interesting things from our own school library. I do remember hanging out at the Stouffville library with my friend Terri Ann, reading a slang dictionary, trying to get each other to read out the definitions for words like prick and ass. I was probably 12 then, and that must seem unbelievably naive now (we wouldn't have found it fun to pronounce the bad words) and I wonder if I would have been a terror if I had an internet connection back then?

Then we moved to Lethbridge, where I can't even picture the library in my mind. I would have to guess I was never there (though there is a chance one of the youth orchestras I was in practised in a library basement?) That doesn't mean I didn't read, because I bought a lot of Stephen King over those years.

I moved up to Edmonton, and again, I was happy to buy my books and Dave and I made near weekly trips to the Wee Book Inn to look for interesting paperbacks. When I was in college there, I used the public library a lot for research (and for some reason don't really remember using the college library). When I was in my last semester, the city introduced a $20/year user fee for a library card, and I just couldn't spare the money. They did have a policy that you could have the fee waived if you signed a declaration saying you couldn't afford it, but that would have been embarrassing. I just stopped using the library.

When we first moved to Cambridge, now a family of three, it was into a really small townhouse, but we were overjoyed to have it. I was also delighted when, soon after, a new building was erected for the high school nearby, and as a savings measure, a branch of the public library was put it in. What a great blending of needs, I thought: the high school will have a fully stocked library and my kids will become a part of the larger educational community before they ever start school. What I didn't count on, however, was that high school students -- with their shoving and cursing and all around terribleness -- would be loitering around the common entrance if I took the girls during school hours. But, the oasis of the library itself was worth running the gauntlet though.

Our library has wonderful programs for kids and I really appreciated being able to bring my girls from the time they were babies until they were old enough to lose interest. Storytimes with crafts happened a few morning a week, and every Wednesday evening, and since I didn't have a car, it was the only place we could go that was walking distance (excluding the parks that we loved for outdoor play time). In the summer, as we didn't have air conditioning at home, it was a cooled off paradise where we would spend many happy hours. In the winter, it was a cozy shelter from storms outside (and easily reached by mother-powered stroller). When the girls got older, there were summer reading competitions that kept them reading while school was out, and they eventually attended programs on their own. Despite all my efforts at raising the girls in a book rich environment, however, neither is really a reader now. (But, as I remember it, I wasn't quite such a fanatic myself as a teenager, and to be fair, they read their devices constantly.)

Two stories about our library: When Mallory was only around 2, I had brought her and Kennedy to a Wednesday evening program. Mallory was too young to actually attend, so she and I looked at books in the children's section while Kennedy mastered glitter glue inside the program room. Out of nowhere, Mallory leaned away from me and barfed up a giant, orange, carrotty mess onto the carpet and then started crying. I jumped up, soothing Mallory while the lovely male librarian came scurrying over, and wincing at the pile of barf, told me I could go clean up my baby while he cleaned up the barf. I protested that that couldn't possible be his job and he bravely smiled and said, "Yes, actually, it is my job. Don't worry about it." Mal is totally embarrassed by that story, and as I rarely miss a chance to point out that lovely male librarian to her, I can't miss a chance to memorialise the event here.

My other story relates to Hanagarne's embarrassed interaction with the porn-watching homeless guy. It caused quite a stir here in Cambridge when a former police officer attempted to protest the availability of porn on the library's computers after he saw a homeless man downloading some. It became this huge censorship issue, and in the end, it became an issue of human rights: poverty advocates wanted to know just who the hell all of us with private access to pornography were to block the only access that these disadvantaged people had. And so far as I know, the end result was that our libraries have neither filtered access to porn from the public computers nor is there a policy of librarians themselves intervening when people complain.

So I'm full circle back to censorship and need to wonder if my mother would have hotfooted it down to the library to insist that my computer access not be censored, or is that level of righteousness reserved for Lady Chatterly's Lover? (Not that that's what I was trying to take out as a child, lol.) Is access to information an absolute? A human right? And what role should a library play in a changing world? Certainly, I took advantage of as many children's programs as I could for the girls, and they're trying to remain relevant locally: rebranding as Idea Exchange (we're not just a library!); encouraging people to bring food and drinks in with them (why go to Starbucks when we have free wifi too!); holding conversation circles (no one will shush you!); there's even a rarely used Rockband set up for "jamming". And as I said, I use the library constantly myself; although I reserve all my books online and no longer even need to interact with a librarian as I use the self checkout. For what I need now, a vending machine would work just as well. A vending machine and my laptop. So, despite my long history with libraries, and despite the local efforts to remain relevant, I don't know if Hanagarde and his platitudes have it right: with a smart device and an internet connection, don't we all have a non-censored library in our pocket anyway?