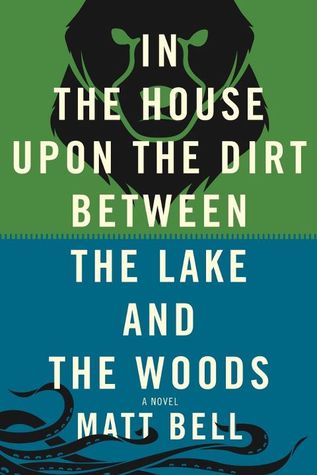

That was the question I worried at, that I gnawed at like a bone, a cast-off rib too stubborn to share its marrow. And when at last that bone broke, what truth escaped its fracture, was by it remade: for even our bones had memories, and our memories bones.In the House upon the Dirt between the Lake and the Woods is a strange and twisted narrative; a lost Brothers Grimm from the pre-sanitised days of a medieval Black Forest; a time when it was perfectly reasonable to tell tucked-in children about a huntsman chopping open the conscious wolf's belly to free Little Red. This is not a fable – with some aphoristic kernel at its center – but a fairy tale; red in tooth and claw and bursting through the limits of the plausible.

It begins with a young married couple, unnamed, who have left their families and travelled to an unreal and virgin hinterland in which to begin their lives together. While the husband fells trees to build their house, the wife has a violent encounter with a cave bear that leaves them without material possessions, but grants the wife the ability to sing anything into being. When she suffers a series of miscarriages, the wife sings down the destruction of their world, and as the husband continues to pressure her to try and try again for a baby, the wife turns to subterfuge to grant his wish. As a meditation on grief and loss, gender roles and marital expectations, In the House has much to say.

What if I could become deep father and she deep mother and the foundling or the fingerling our deep child, and what if the whole world I had known – all that lake and dirt and house and woods and bear and what was not a bear, all that father and mother and child and ghost-child and moon and moons – what if all that was failed forever, doomed by our years of childlessness, our despair over those long years?

Yet In the House doesn't present a straightforward allegory, but rather, is relentless in its offering of outlandish ideas; each sentence wondrous strange, but the paragraphs somehow not adding up to something more. Perhaps it should be approached like a book of poetry: consumed in smallish chunks and only expecting the whole to be vaguely cohesive. I cannot deny that I was swept along by paragraphs like this one:

At the sound of my voice, the bear slipped, staggered, the front of her body lower than the back and now sliding sideways, and as I tightened my grip on the pommel of a protruding shoulder blade, the bone shattered, became a handful of dust. The bear cried out, bent the wide wedge of her head back upon me, and she was near blind then too, one eye clouded, the long-drooping other caked with layered rheum and salt, grinding as it turned in its orbit. She opened her mouth to make some warning, but there was so little growl left in her, too little to waste. Snot dripped from her caved nostrils, and the remains of her lips drooled white clumps of thirsty spit, and the cords in her neck jumped between her bones, so that I could see her stretched muscles working her toothless face, that countenance no less fearsome for its lack of skin, of underlying blood with which to make its hate known, and to that face I said, I'm sorry.Yes, this is a lot of quoting, but for a work like this, it seems only fair to let author Matt Bell speak for himself. In the end, I can only say that I was enjoying In the House while I was reading it, but struggled to get through it, and upon reflection, didn't get much out of it but an admiration for its language.

And yet! And always, and no matter. All that was ended, and this too.