The cell squeezed her and the air was hot and fetid. All the joints of her body burned from her frantic twisting against the walls. Her head was pressed into her chest and her legs shot with cramps, but her struggles had worked – one wall felt weaker. She kicked out with all her strength and felt something crack and break. She forced and tore and bit until there was a jagged hole into fresher air beyond...And thus was the worker bee Flora 717 hatched into her hive. Large and ugly, doomed to be immediately destroyed by the caliper-wielding police (Deformity is evil. Deformity is not permitted.), Flora was saved at the last minute by Sister Sage; a beautiful and privileged bee of the Priestess class who seems to have special plans for the abnormal bee.

This was the Arrivals Hall, and she was a worker.

Her kin was flora and her number was 717.

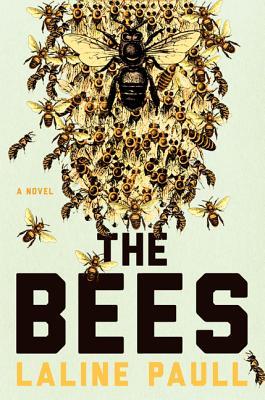

The Bees by Laline Paull is a strange mix of fantasy and nature story that details a year in the life of a honeybee hive, as experienced by its inhabitants. There is much curious biology (Do bees really secrete wax from between their bands of fur? Can virgin workers produce fertilised eggs? [And, yes, apparently some species do.] Would one worker bee really be rotated through every task, from nurse to forager?), but the energy and lyricism of the storyline quickly made me want to stop questioning the facts and just enjoy the ride.

In Paull's imagination, a hive is like a religious cult with the Queen as the central focus. The rest of the cult's members are placed in strictly enforced castes – from the Priestesses who enjoy the most influence down to the untouchable sanitation class to which Flora should belong – and order is maintained through daily access to the Queen's Love; a chemical wash that soothes and brainwashes the hive. Secret police deal quick and deadly punishments to nonconformists and every worker is born knowing the hive's Orwellian slogans: Accept Obey Serve; From Death Comes Life Eternal; Only the Queen May Breed. For comedic relief, the rare males are portrayed as lazy and foppish – prone to praising the might of their own dronewood – but their ultimate fate involves one of the book's most violent scenes.

Perhaps trying to explain the recent surge in Colony Collapse Disorder, Paull's honeybees are under stress from climate change (and a rainy season with not enough foraging days), pesticides, the lethal call of cell phone towers, and their historic foes The Myriad (all natural predators, from wasps to crows). In a non-obvious observation, it might be the hive's policy of killing all abnormally-shaped bees that has doomed them – without variation, they can't possibly adapt to changing external conditions (and if this is the ultimate point of The Bees, more should have been made of Sister Sage's mysterious treatment of Flora and the latter's curious paternity).

I really did enjoy this story while I was reading it, but now that it's done, it feels like there was something missing; something deeper. Still, no regrets; The Bees was a worthwhile read.