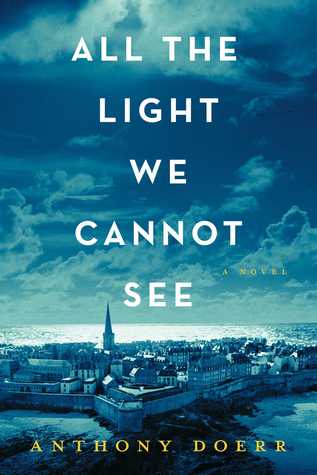

What do we call visible light? We call it color. But the electromagnetic spectrum runs to zero in one direction and infinity in the other, so really, children, mathematically, all of light is invisible.All the Light We Cannot See is a very popular book -- as lyrical and easy to read as a modern day fable -- and as much as I did mostly enjoy it in the moment, this book's overall effect was to leave me unsatisfied. In an interview with the author, Anthony Doerr says that his intention with this book is to have readers ask themselves What would I be doing in this situation? Was the war just good versus evil in the way some History Channel reenactments are skewed to portray World II? As someone who is always wary of moral relativism, I'm not interested in "understanding" what made Nazis tick, I don't think the History Channel needs to work very hard to show that there was a right side and a wrong side in WWII (an alliance with Stalin aside, stopping the Nazis was objectively moral), and any author who would trivialise the actual facts of history in order to use them as the backdrop for a light work of fiction risks normalising that which once horrified us.

The plot of this book switches between the points of view of three characters and hops from the "present" of August 1944 to further back in time in order to reveal the personal histories of these three. Marie-Laude is a blind Parisian girl whose father evacuated with her to his uncle's home in the walled island city of Saint-Malo on the Brittany coast. Werner is a German orphan boy who, after displaying an innate facility for electricity and mechanics, attends a prestigious military training school until called to serve in the army. Sergeant Major von Rumpel is a Nazi art and gem expert, collecting treasures for Hitler's Führermuseum, who spends his army career on the trail of a mysterious diamond -- the Sea of Flames -- said to carry both cure and curse.

Curses are not real. Earth is all magma and continental crust and ocean. Gravity and time. Isn't it?These three characters eventually make their way to Saint-Malo (revealed immediately -- not a spoiler) and are all present when the Americans firebomb the city. These sections set in the present are tense and exciting, but as we are eventually made to sympathise with each of their situations and motivations, the Americans' wilful destruction of a centuries old city is hinted to be the most unfathomable crime here. Not enough relativism? How about the only Russian soldiers shown are drunken-vandal-rapists? Still not enough? How about Marie-Laude, involved in a small way with the French Resistance, worriedly asking her uncle, "Are you sure we're not the bad guys?"

You know the greatest lesson of history? It’s that history is whatever the victors say it is. That’s the lesson. Whoever wins, that’s who decides the history. We act in our own self-interest. Of course we do. Name me a person or a nation who does not. The trick is figuring out where your interests are.Okay, the politics of this book didn't work for me, but what about the writing? Like in a fable, there were so many enchanting images -- the ten thousand keys of the Natural History Museum, puzzle boxes and miniaturised cities, a grotto by the sea, a cursed gem -- and Doerr works overtime to inflame the imagination. With a multitude of adjectives and vivid imagery, the effect comes down to a reader's taste. According to the Washington Post:

I’m not sure I will read a better novel this year…Enthrallingly told, beautifully written and so emotionally plangent that some passages bring tears, it is completely unsentimental — no mean trick when you consider that Doerr’s two protagonists are children who have been engulfed in the horror of World War II.And The Guardian:

Doerr's prose style is high-pitched, operatic, relentless. Short sharp sentences, echoing the static of the radios, make the first hundred pages very tiresome to read, as does the American idiom…No noun sits upon the page without the decoration of at least one adjective, and sometimes, alas, with two or three. And these adjectives far too often are of the glimmering, glowing, pellucid variety.And an example of the writing:

To shut your eyes is to guess nothing of blindness. Beneath your world of skies and faces and buildings exists a rawer and older world, a place where surface planes disintegrate and sounds ribbon in shoals through the air. Marie-Laure can sit in an attic high above the street and hear lilies rustling in marshes two miles away. She hears Americans scurry across farm fields, directing their huge cannons at the smoke of Saint-Malo; she hears families sniffling around hurricane lamps in cellars, crows hopping from pile to pile, flies landing in corpses in ditches; she hears the tamarinds shiver and the jays shriek and the dune grass burn; she feels the great granite fist, sunk deep into the earth's crust, on which Saint-Malo sits, and the ocean teething at it from all four sides, and the outer islands holding steady against the swirling tides; she hears cows drink from stone troughs and dolphins rise through the green water of the Channel; she hears the bones of dead whales stir five leagues below, their marrow offering a century of food for cities of creatures who will live their whole lives and never once see a photon sent from the sun. She hears her snails in the grotto drag their bodies over the rocks.If you like that, you'll love this book. (And as an aside, in that same interview above, Doerr said that the extremely short chapters in this book are because: My prose can be dense. I love to pile on detail. I love to describe… It's like I'm saying to the reader, "I know this is going to be more lyrical than maybe 70 percent of American readers want to see, but here's a bunch of white space for you to recover from that lyricism.") This is the kind of book that I feel bad for not liking -- you have to be a monster not to empathise with the blind girl and the orphan boy who are pawns in the jaws of history -- but if an author deliberately tries to manipulate me with fictional characters like this, he better have something deep to say. I completely understand why All the Light We Cannot See is a popular best-seller -- it's a thriller involving sympathetic characters in one of the most psychically scarring times in human history -- but it was not for me.

God is only a white cold eye, a quarter moon poised above the smoke, blinking, blinking, as the city is gradually pounded to dust.

Edit from April 20:

So apparently, this book that I gave two stars to won the Pulitzer Prize for 2015, making it one more in a list of winners that underwhelmed me. According to the Prize's FAQ:

There are no set criteria for the judging of the Prizes. The definitions of each category (see How to Enter or Administration page) are the only guidelines. It is left up to the Nominating Juries and The Pulitzer Prize Board to determine exactly what makes a work "distinguished."

Obviously, the judges are looking for something different than I am, and they're the experts, and there ya go.