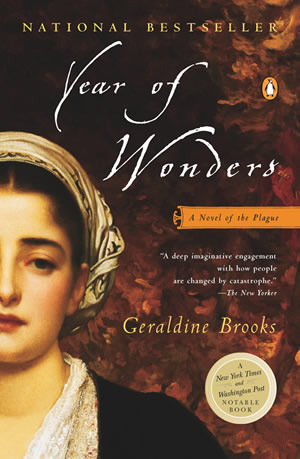

We know that God sometimes has spoken to His people in a terrible voice, by visiting dread things upon them. And of these things, Plague -- this venom in the blood -- is one of the most terrible. Who would not fear it? Its boils and its blains and its great carbuncles. Grim Death, the King of Terrors, that marches at its heels. Yet God in His infinite and unknowable wisdom has singled us out, alone amongst all the villages in our shire, to receive this Plague.Geraldine Brooks has a definite method and a definite style: Finding some fragment of true history (in this case the very real "plague village" of Eyam in England and its citizens), she expands the little that is known into a living, breathing reality. In 1665, the Plague was introduced to the village by an infected bolt of cloth and the rector -- Michael Mompellion in Year of Wonders and William Mompesson in real life -- made the courageous suggestion that the villagers close their borders (neither allowing visitors to enter or citizens to flee) in order to prevent infecting anyone else. The villagers agreed, and over the course of the next 14 months, about two thirds of them died.

In the afterword it states that one of the few letters that remain from William Mompesson mentions the maid whose tireless work the rector was ever grateful for, and on that basis, such a maid is the narrator of this book: a young widow named Anna Frith. I found Anna to be likeable and sympathetic, an excellent eye-witness to the tragedy, but there were queer inconsistencies -- some nearly anachronistic -- in her character. She was at first resistant to learn about herb-lore because women with such knowledge are often accused of being witches (and there is a dramatic witch-hunt scene in this book), but once she starts tending to the sick, she not only uses herbs but recites an overheard chant that calls on the seven directions and invokes the blessings of the grandmothers over the work. Although Anna had faithfully believed in Providence and the Will of God her entire life, she waxes philosophical about whether the Plague might not be a purely natural phenomenon. Although Anna's father had been a mean and abusive drunk, as she relates his entire life story to a friend, she realises how his own hard childhood had made him the man he would become -- and I really didn't buy this 17th century psychoanalysis. I also didn't believe that, knowing women in mines were considered bad luck, Anna would enter one for the first time in her life and attempt to dig out enough ore to prevent an orphan from losing her claim. On the other hand, Anna's goodness and generosity of spirit made me root for her, and no matter how implausible her efforts, I wanted her to succeed. In the opening scene of Age of Wonders, Anna states that she had lost everything in the preceding year, so I won't consider this a spoiler:

When I woke, the light was streaming through the window. The bed was wet, and there was a wild voice howling. Tom’s little body had leaked its life’s blood from his throat and bowels. My own gown was drenched where I’d clutched him to me. I gathered him up off the gory pallet and ran into the street. My neighbours were all standing there, their faces turned to me, full of grief and fear. Some had tears in their eyes. But the howling voice was mine.As one might imagine, there is much loss and grief in this book and parts of it had me blubbering -- some might find it overwrought, but it was touching to me. There was also evidence of much research -- the everyday life and customs of the people were deftly explored. So much about this book was going so well, and then, there's the strange ending.

I can see how some would find the ending to not be consistent with the rest of Year of Wonders, but I have to note, it is entirely consistent with what I've read of Geraldine Brooks: Caleb's Crossing and People of the Book both feature women narrators who seek knowledge that their families or society don't approve of, and they make decisions that may not seem to follow from what comes before. As this was Brooks' first novel, it would appear to be her first attempt at having a character make this leap, and having seen her write it more successfully elsewhere, I'm somehow more willing to forgive its clumsiness. This was interesting to me -- reading Brooks' first novel of this kind last -- because I can see all the same themes playing themselves out (and even note the "Mussulman Doctor" who might be the same who makes an appearance in People of the Book). I still need to read March before I can decide if I'm really a fan or not, because while I liked this book, I wasn't blown away.

I had lost my sunglasses this week -- which I always wear when I walk the dog -- so didn't like the one day I had to walk with a ballcap on instead. And, boy, was I glad I looked harder for them the next day: As I was walking along, first that scene above where the baby dies in Anna's arms overnight had me blubbering and sniffling, trying not to let tears spill from my eyes, and then after a few minutes (of listening time -- the scene happens a few days later), Anna's other son dies. As he's laying on his pallet, sick and trembling, he calls out, "Mummy, Tommy needs you" and at the mention of her dead baby's name, Anna's milk comes in and soaks the front of her smock. "It's okay, Jamie, Tommy's here with me, don't worry" -- I'm blubbering and grateful that no one is walking around me -- and then Anna tells her little boy a fairytale about a little boy who needs to be brave enough to enter a strange door and leave the world he knows behind. I was a wreck as these children died, and as always, I am grateful to any book that touches me like that.