At first, when I gave out a Latin declension, father was amused and laughed. But my mother, working the loom as I spun the yarn, drew a sharp breath and put a hand up to her mouth. She made no comment then, but later I understood. She had perceived what I, in my pride, had not: that father's pleasure was of a fleeting kind -- the reaction one might have if a cat were to walk upon its hind legs. You smile at the oddity but find the gait ungainly and not especially attractive. Soon, the trick is wearisome, and later, worrisome, for a cat on hind legs is not about its duty, catching mice. In time, when the cat seems minded to perform its trick, you curse at it, and kick it.

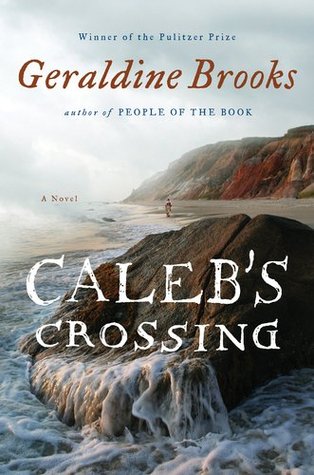

Such is the fate of Bethia Mayfield: possessed of a keen intellect and a thirst for knowledge, but living in a Puritan settlement on Martha's Vineyard during the mid-1600's, this minister's daughter must watch uncomplainingly as her dull-witted brother, Makepeace, fails to grasp the education that their father intends for him (and him alone). At first, I feared that Caleb's Crossing would be too very much like People of the Book: in that novel, the author Geraldine Brooks leapfrogs backwards in time, making the point in every era that women must seek the knowledge that would be denied to them and that there is no greater historical villain than the white, Christian male (from Slobodan Milošević to Adolf Hitler to King Ferdinand of Spain). While I appreciate that this is a common progressive viewpoint, I grew weary of its belabourment in the last book and was, therefore, much relieved to discover that that wasn't the point of this book at all: although Bethia does yearn for the forbidden knowledge, she searches for and submits to God's will in every tragedy and disadvantage she experiences (including the disadvantage of her sex) and, as a result, this book felt much more subtle and empathetic. (And for some reason I feel compelled here to make clear that I don't personally submit to any fundamentalist religious views but rather appreciate that Bethia's character, in her time and place, did her best to reconcile her yearnings with her beliefs -- it was an authentic-feeling literary choice.)

Also similar to People of the Book, with Caleb's Crossing Brooks started with a sliver of historical fact, the actual person of Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, and expanded what the journalist in her could ferret out into a fully realised historical narrative. Knowing he was an actual person, I googled Caleb when I was about halfway done and found this portrait:

And I want to warn anyone who follows my path -- don't make the same mistake that I did and read the few lines that accompany the portrait because they tell all that is known of Caleb and, in a small way, ruined the narrative for me. (Which is why I don't want to give away anything at all that happens to Caleb here.)

When Bethia and Caleb meet in the wilds of the island as preteens and form a friendship based on teaching each other their very different ways of life, it is a meeting of equals -- Brooks doesn't hold either culture up as the superior, and throughout the book, there are advantages and disadvantages shown to each, and there are good and bad people in each community (with, for the most part, the people acting according to their sincere beliefs). That Bethia loves Caleb as a brother makes her the perfect witness and chronicler of his life -- a literary choice that was likely more interesting than if Brooks had straight-out told Caleb's story from his own point of view.

More specifically about the book itself -- It is written in a diary form by Bethia's character and covers three periods in her life: her girlhood on the island; her young womanhood on the mainland; and from her deathbed as an old woman (which has the advantage of her being able to look back at the differences that then existed since the time of the King Philip’s War in 1675 that ended the era of peaceful co-existence between the English and the Natives). As a novel set spanning the turn of the 18th century, the language is somewhat formal but not off-putting -- just enough of a flavour of the era without needing to mentally translate anything. The description of the Puritan and Native settlements were interesting and evocative of the time. The characters were fully formed and consistently acted according to internal logic, allowing many (especially the dullard Makepeace) to evolve in a satisfying way. This is a really well written book, smart with heart, and I thoroughly enjoyed it; the slight whiff of dramatic irony inherent in Caleb's true history was successfully expanded into a lens on a fascinating time.

I'm going to allow myself to put the spoilers here that I didn't want to put on goodreads (so I suppose this is a warning). I have a "friend" on that site who read this book also recently and her review ends: SPOILER ALERT....SPOILER ALERT....SPOILER ALERT...SPOILER ALERT... One of the reasons I liked this book was that I was sure that Brooks would ruin it by having Bethia and Caleb become lovers, and she didn't, thank God and good sense. And that's an interesting point because while reading Caleb's Crossing, I got the sense that Caleb and Bethia would have been perfectly matched if their cultures would have allowed them to be together. And here's my own situation that I feared would be revealed in the book: When the story jumps ahead to Cambridge, Bethia says something like, "I suppose I should explain how I came to be on the mainland in my condition". She goes back to talk about living on the island and the one time that Makepeace confessed to a litany of sins in the weekly Meeting, ending with lust (a fact that thoroughly surprised Bethia because he had never shown interest in any girl). Soon after, their father dies in a shipwreck, leaving the siblings to live alone together, and I was sure, SURE, that Makepeace had lusted after his sister, and after having his jealousy provoked by imagining that Bethia loved Caleb, I was certain, CERTAIN, that he would rape her, making her pregnant, and forcing her to be exiled to the mainland. It felt like the inevitable path of the story and I would have HATED it -- so when it turned out that her "condition" was the result of her penny-pinching grandfather proposing to sell Bethia into indentured service in order to pay for her brother's education, it was both more satisfying and more horrifying than what I had predicted.

Eventually, Makepeace wants to drop out of school (he never was a scholar) and arranged for Bethia's former suitor (the young man that their father had selected as a match for her) to buy out her indentureship as a prelude to their being married. Knowing that she wasn't happy with that arrangement, the Master of the school she works at lets Bethia know that his own son -- a 26 year old scholar/tutor at Harvard -- was also interested in courting her. She meets him and is overwhelmed by the prospect of a life with books and knowledge and stimulating conversations. Bethia is forced to choose between her father's selection (Noah Merry, a good-natured son of a farmer/mill owner who could provide her with a lifetime of plenty on the island that she so piteously missed) and the new opportunity (a fiercely intelligent man who is attracted to Bethia's mind, someone who wants an intellectual partner to accompany him through many more years of penniless student life in Cambridge and, perhaps, Padua); she needed to decide whether she would prioritize her heart or her mind -- and she chooses her mind. When Noah Merry does buy her freedom, while confessing that he loved another, he presents her with her indentureship papers, making her free to choose the scholar -- or no one at all. At this point is when I started to wonder if the author would throw Bethia and Caleb together -- he alone would have satisfied both her heart and her mind as they had long shared a love of the nature of their island home as well as their philosophical debates. I wanted the relationship to happen, but I also knew it couldn't have in that time (although the author said many times that Caleb could have passed for Spanish or Italian -- maybe they could have run off together?)

Is it ever thus, at the end of things? Does any woman ever count the grains of her harvest and say: Good enough? Or does one always think of what more one might have laid in, had the labor been harder, the ambition more vast, the choices more sage?And, of course, here is where I make it personal: I'm afraid I'm at the stage of counting the grains of the harvest of my own life and wonder at how I got here. School was always easy for me but I never had an intellectual fire; no thirst for learning, really. I went to University until it bored me (mostly because I didn't work very hard at it) and then later decided to make a practical choice and got a 2 year College diploma, which I've never put to use. Twenty years later, I haven't worked in decades, my children no longer really need me to be around all of the time, and I feel like I have squandered any gifts I ever had -- the labour could certainly have been harder, the ambition more vast, the choices more sage. I got married at 23, not because I needed Dave to take care of me for the rest of my life, but because it seemed the reasonable next step -- but what if I had concentrated on just me, on just the improvement of me, at that tender age instead? I don't know if anything would have been different -- I still would have lacked that fire, that purpose. And then there's my own daughters:

Kennedy just finished her first year of University, where she is studying Theater Arts and discovered a love for Art History (in which she intends to minor). I don't know if there are any two degrees that are more clichely "useless" than those, lol, but they are her passion and she has our full support (and I do mean that: I say "useless" to acknowledge the common perception only). Mallory, meanwhile, has confirmed plans to become a Museum Curator one day and plans to eventually get a PhD in History (another cliche, I fear) despite being an essentially lazy student, as I was. She, also, will have our full support in this. I was talking about the girls to my friend Beth the other day and she told me that her niece had gotten a degree in Psychology, and then realising that that was not a career in itself, she went back to College and got a diploma in HR Management as well, and is now on the path to success. I know that the newspapers are filled with hand-wringing about kids today getting useless degrees instead of practical training so I decided to share the story of Beth's niece with my girls -- in particular telling Mallory that museum curating is apparently a 2 year course at the college the niece attended. They were both nonplussed by the story and I don't blame them -- if there's one thing they somehow learned going through school it's that "smart kids" go to University and "dumb kids" go to College (despite the fact that their own mother has only a College diploma...) Mallory said that she wasn't looking at post-secondary just as training for a job but that she wants the years of learning, the specialised knowledge, that comes with a PhD. I do hope that's true -- Dave and I have nothing against the girls following their dreams; all we honestly want is their happiness. Don't they say, "Do what you love and the money will follow"? I also have to wonder to what degree our support reflects the fact that they are girls -- do we assume that one day they will both be married and have the support of their husbands if their own career dreams don't work out? There may be a bit of that, but since Dave's parents supported him when he went for a Theater Arts degree, we're probably more willing to encourage the pursuit of fulfillment over the pursuit of money alone. (And can also see how such a degree can be put to other uses -- there's always law school or politics for Kennedy...)

In the end, I suppose I married Noah Merry -- the good-natured, hard-worker who has provided me with a safe and comfortable life. Bethia shrank from that choice (before the option was removed for her) but, then again, I'm not Bethia. Would I have preferred to have married a man who challenged my mind? Dave's no dummy, but I learned long ago that he's not interested in discussing the things that inflamed my imagination (Quantum Physics, anyone?) My sisters-in-law all have careers (CGA, RMT, Speech Path), so couldn't I have worked on my own fulfillment while also raising a family? Like Bethia from her sickbed trying to imagine what might have happened had Caleb lived, I too must acknowledge that the what-ifs are a useless pursuit. And since I mentioned Caleb's death, here's the scant info that is known about the historical figure:

In 1665, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck became the first Native American to graduate from Harvard University.

Cheeshahteaumuck, of the Wampanoag tribe, came from Martha's Vineyard and attended a preparatory school in Roxbury. At Harvard, he lived and studied in the Indian College, Harvard's first brick building, with a fellow Wampanoag, Joel Iacoomes.

Cheeshahteaumuck died of tuberculosis in Watertown, Massachusetts less than a year after graduation.

Apart from Cheeshahteaumuck and Iacoomes, at least two other Native American students attended the Indian College at this time. Eleazar died before graduating and John Wampus left to become a mariner. Iacoomes was lost in a shipwreck a few months prior to graduation, while returning to Harvard from Martha's Vineyard. Cheeshahteaumuck is believed to have been the only Native American to have graduated from the Indian College during its years of operation. These first students studied in an educational system that emphasized Greek, Latin, and religious instruction.

And there's the dramatic irony -- we can't know what did prompt Caleb to leave his traditional home and way of life to pursue a Classical educational, but for him to die within a year of graduation (and for his cohorts to die -- or in one case drop out --before graduation) makes me wonder if the sacrifices could possibly have been worth the rewards. When Caleb dies in the book, having received through Bethia some secret words of his uncle the pawaaw (wizard), his final death song was incredibly poignant and touching; in the end, he knew where he belonged and to where he was heading; and that's the most that any of us can hope for, in the end.