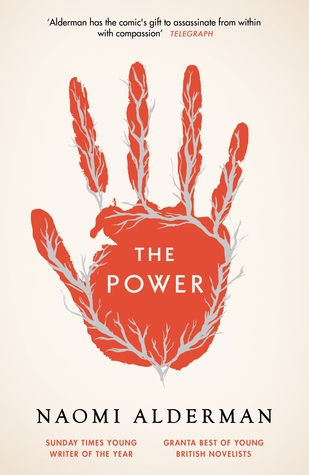

The Power

It doesn't matter that she shouldn't, that she never would. What matters is that she could, if she wanted. The power to hurt is a kind of wealth.

The Power by Naomi Alderman is the 2017 winner of the Bailey's Women's Prize for Fiction, and while that fact might risk isolating this work as feminist “chic lit” (which, after reading the framing device for this book, would be nicely ironic), I am delighted that Anderson won; delighted to have been prompted to read this intriguing novel that asks the simple question, “What would happen if women were suddenly stronger than men?” Because that's what happens: Out of seemingly nowhere, a powerful organ (likened to the galvanic plaques in electric eels) is awakened in adolescent girls, and their ability to overpower their male peers leads the entire world on a path that overturns the patriarchy. Power was always about brute force, and once it's in the hands of women, they are every bit as brutal as their former subjugators. The exploration of this idea feels both inventive and inevitable, and the conclusion that Alderman arrives at is pitch perfect. I didn't love everything about this novel, but I had an undeniable visceral reaction; it spoke to me and my fears and that makes it feel vital in a highly personalised way. The following quote, from when a hardassed loner first finds herself welcomed into a group of powerful young women, sums up my early reading experience:

Roxy has a feeling she can't quite name, can't really place. It makes her a little soft inside, a bit teary.

In the beginning, I was constantly on the verge of tears: my breath hitched as the girl in the Nigerian supermarket was being harassed by an older man, and I was vicariously thrilled to watch her leave him twitching on the floor with just one touch; my heart pounded as the sex slaves chained in the Moldovan cellar were transferred the power to free themselves; I mentally marched along with the women in Delhi who vowed that they would never again be afraid to walk the streets at night. From high school girls being able to back up their “No means no” with force, to a woman mayor finally standing up to the alpha male governor of her state, to a goddess cult arising that puts Mary at the head of the Christian Trinity, it all made me feel soft inside; as though I hadn't known my own desires until they had been named.

You have been taught that you are unclean, that you are not holy, that your body is impure and could never harbour the divine. You have been taught to despise everything you are and to long only to be a man. But you have been taught lies.

I nodded along knowingly as the official male reaction ranged from trying to contain or cure the new female powers (even sending armoured male stormtroopers up against teenaged girls), to online extremism, to accepting their subordinate role. I cringed as the women's powers grew over the years and their use changed from defensive to offensive; it felt extreme to watch rapacious women walk through the woods at night, electricity arcing from hand to hand, as they searched for the men hiding in the bushes and trees. As the abuses grow, and as the chapter titles hint that we are counting down to a game-changing event, I began to identify with the narrative less emotionally and reacted more cerebrally; a shift that felt like a lessening in my engagement. The big climax does feel inevitable – and was the ending that I wanted (after all, you can't get there from here) – and then the concluding framing device felt so very very clever that it ticked my enjoyment level up another notch. But then I realised that this was pretty much the same framing device used in Pierre Boulle's Monkey Planet, which made me realise that this book is pretty much a gender-based Planet of the Apes, and while that made it feel less clever, I can't deny that I was emotionally affected by the concept of adolescent girls finding their powers and it made me wonder, “Is the difference between men and women really just a matter of physical strength?” I don't know if I would answer that question the same way as Alderman did (is gender just a "shell game"?), but I thoroughly enjoyed her take on the concept.