A Gentleman in Moscow begins with this brief hearing in 1922: in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, Russia's aristocratic class are being purged through such hearings; usually ending with the defendant stood against a wall. Due to a poem he had once written that marked him as one of “the heroes of the prerevolutionary cause”, the tribunal decides to spare Count Rostov's life, condemning him instead to a life sentence of house arrest at the luxurious Metropol Hotel in the heart of Moscow. As he has been occupying a comfortable suite of rooms in the hotel for the past four years, Rostov accepts his sentence with equanimity, but upon returning to the Metropol, he is nearly ruffled to discover that he is to be moved to a hundred square foot storage room in the belfry, with a three-legged bureau and a postage stamp-sized window. Nearly ruffled, but if a lifetime of refinement has taught the Count anything, it's to meet every circumstance with stoicism and grace and impeccable manners. And so begins Rostov's decades of confinement. (I want to note: I was privileged to receive an ARC of this book, and while that means I'm not really supposed to quote from it, I couldn't resist and will add the caveat that anything I quote here may not be in its final form.)Prosecutor Vyshinsky: State your name.

Rostov: Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, recipient of the Order of Saint Andrew, member of the Jockey Club, Master of the Hunt.

Vyshinsky: You may have your titles; they are of no use to anyone else. But for the record, are you not Alexander Rostov, born in St. Petersburg, 24 October 1889?

Rostov: I am he.

Vyshinsky: Before we begin, I must say, I do not think that I have ever seen a jacket festooned with so many buttons.

Rostov: Thank you.

Vyshinsky: It was not meant as a compliment.

Rostov: In that case, I demand satisfaction on the field of honor.

Rostov's unflappability is the great charm of this book – he meets with indignities and absurdities with a smile and a quip; perfectly phrased responses that had me smiling throughout. The Count also forms great friendships throughout the years – with the hotel staff, other frequent guests, and most notably, a serious-minded little girl – and the ever-deepening meaning that Rostov finds in these relationships over the years is a pleasure to watch. Over the decades, the hotel hosts everyone of importance from Stalin to Khrushchev, and while Rostov finds himself, as a Former Person, suspended in a place outside of politics, he knows several people who are early idealists regarding the Revolution, and their excitement (and later disillusionment) feels just authentic enough to give a flavour of the times without getting weighted down by dull ideology. The big story arc was satisfying, and the little vignettes were absolutely charming (the sad tale of Rostov's sister and the Lieutenant who toyed with her heart was pure Tolstoy). This is definitely the type of book that I wanted to read quickly but didn't want to have end.

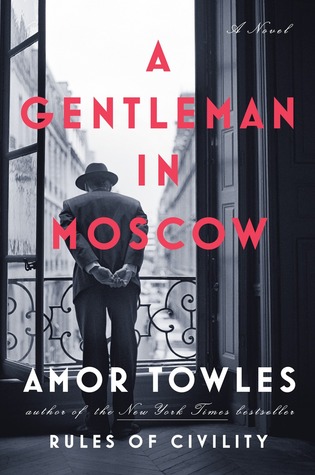

To sleep until noon and have someone bring your breakfast on a tray. To cancel an appointment at the very last minute. To keep a carriage waiting at the door of one party, so that on a moment's notice it can whisk you away to another. To sidestep marriage in your youth and put off having children altogether. These are the great conveniences, Anushka – and at one time I had them all. But in the end, it has been the inconveniences that have mattered to me most.On the other hand, I didn't think that A Gentleman in Moscow was a perfect book: author Amor Towles too frequently skated the thin line between charming and cheesy and it oftentimes felt a little lightweight. Often there were details noted that I assumed would later become important but didn't: like Rostov going to the roof and becoming friends with the handyman/beekeeper, but when the timeline skips ahead (and presumably the old man has died or retired), the Count never again goes to the roof; or when a young woman is given a necklace, is warned to get rid of it as dangerous, yet when she decides to keep it, there are no consequences (it isn't mentioned again) – too many dangling details like this made the whole feel less cohesive. And one last complaint: Rostov gets away with so much in this story, and without giving any spoilers, I'll just say that as a prisoner and as the presumed enemy of the hotel's eventual all-seeing manager, would his room really never have been searched in all those years?

Our lives are steered by uncertainties, many of which are disruptive or even daunting; but...if we persevere and remain generous of heart, we may be granted a moment of supreme lucidity – a moment in which all that has happened to us suddenly comes into focus as a necessary course of events, even as we find ourselves on the threshold of the life we had been meant to lead all along.But, to complain too much would be petty of me when I found A Gentleman in Moscow to be an enjoyable read. I can see this book having wide appeal and I wouldn't hesitate to recommend it as a thoroughly pleasurable way to while away the hours, whether tilted back on your chair in an attic bedroom or seated between two potted palms in the lobby of the fabulous Metropol Hotel.