I felt that not only in my book but in novels in general there was something that truly agitated me, a bare and throbbing heart, the same that had burst out of my chest in that distant moment when Lila had proposed we write a story together. It had fallen to me to do it seriously. But was that what I wanted? To write, to write with purpose, to write better than I already had? And to study the stories of the past and the present to understand how they worked, and to learn, learn everything about the world with the sole purpose of constructing living hearts, which no one would ever do better than me, not even Lila if she had the opportunity?As this is the third installment of the Neapolitan Novels – and as, indeed, all four volumes may be considered one continuous work – I don't feel it necessary to go over, once again, what is specifically intriguing about Elena Ferrante's writing; except, perhaps, to point out that, as in the quote above, it seems to be true that in her novels, Ferrante has the ability to capture the living heart, bare and throbbing (and I am grateful that she, herself, has given me the words, finally, to capture the experience of reading these remarkable novels). Spoilers (and presumably fewer commas) from here.

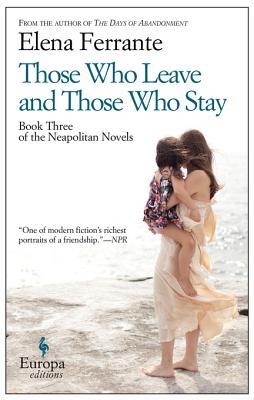

As Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay opens, Elena recalls the last time she met with Lila in the old neighbourhood in Naples, five years earlier in the winter of 2005. Even as Elena is, indeed, writing about Lila on her computer, she's remembering that in this exchange Lila warned her that if she ever decides to write about their friendship, Lila would come look on her computer, read her files, and erase them. When Elena laughed and said that she was capable of protecting herself, Lila warned, “Not from me.” I have never forgotten those three words; it was the last thing she said to me: Not from me. I love the menace in that and I can't wait to see if Lila makes an appearance in the present before the fourth installment ends. From here, Elena rewinds and picks up the narrative from the end of The Story of a New Name; in a bookstore in Milan, with Nino Sarratore defending the merits of Elena's debut novel at her first author appearance.

As I've noted before, these books not only capture the history of a friendship, but the history of Italy as well, and as childhood friends must choose sides between the Communists and Fascists who battle for control of their neighbourhood, city, and country, the friction escalates from a war of words to one with sticks, and knives, and guns. Lila is still working in deplorable conditions in the sausage factory in order to provide for her son, Rino, and unwittingly, she becomes the leader in an effort to unionise. When Lila suffers a breakdown and sends for Elena – herself now married to a professor and living in enviable conditions – Elena realises that, once again, she has overestimated the value of her own life:

I feel like the knight in an ancient romance as, wrapped in his shining armor, after performing a thousand astonishing feats throughout the world, he meets a ragged, starving herdsman, who, never leaving his pasture, subdues and controls horrible beasts with his bare hands, and with prodigious courage.Again, even when Elena seems to be winning at their unacknowledged competition, Lila won't let her win. Soon the scales begin to tip in the other direction: Elena – burdened with the duties of motherhood and an unhappy marriage – finds herself unable to write another successful novel, and Lila – after quitting the sausage factory, returning to the neighbourhood, and consenting to a sexual relationship with the long-suffering Enzo – has her own skills as an early computer expert (gleaned while helping Enzo with his night courses) recognised, and by the end, she's working for the mobster Michele Solaras, earning in excess of 400 thousand lira/month (and for comparison, Elena was considered rich by her family when she was paid 200 thousand lira for her first novel). In the end, Elena breaks free – leaving her family for Nino, the final scene of this book sees the pair flying to France together – and the reader will need to wait for the fourth book to see where the scales will finally settle themselves.

While many of the characters in these books are sympathetic to and can make the case for the necessity of a Communist revolution in 1960s-70s Italy, in this volume, Elena discovers Feminism and it's through this lens that she's finally able to write a second book. Whether looking at Tolstoy's Anna Karenina or Flaubert's Madame Bovary, Elena finds that all of the models of femininity have been created by men (which would make it the ultimate in irony if the pseudonymous Ferrante – the author who is lauded everywhere for capturing the essence of the female experience – turns out in the end to have been a male writer), and along this line of thinking, she is shocked to discover that what has been a challenge to her throughout school has been her efforts to change her mind into a masculine one; and as the flipside, she realises that what makes Lila a special kind of genius is that she has always refused to mold her own mind to the dominant masculine norms. To the reader, however, there's irony in the fact that Elena, even after her eureka moment, needs the approval of a male mind to justify her efforts; she doesn't know if this second book is any good until Nino tells her so.

As a final thought, I am continually intrigued by Elena's struggle between the Neapolitan dialect and actual Italian (I wouldn't have thought that these were two separate languages), and it's interesting to ponder on how the words one uses not only reflect culture but create it; you can't express the thoughts for which you haven't the words, as in:

Lila proceeded to talk generally about her sexuality. It was a subject completely new for us. The coarse language of the environment we came from was useful for attack or self-defense, but, precisely because it was the language of violence, it hindered, rather than encouraged, intimate confidences.The Neapolitan Novels have been an intriguing journey so far and I am on the ambivalent cusp of the final leg: I am desperate to both reach the finish line and stretch this experience out for as long as possible.