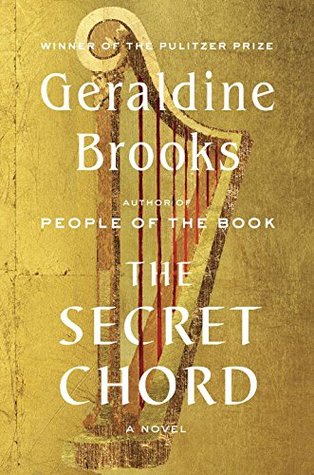

When I realised that The Secret Chord was about King David, I mused that all I really know about him is that he took down Goliath while still a boy and that he played the harp to please the Lord (Hallelujah). That's pretty much the point of this book: Early on, David's resident prophet and advisor, Natan, proposes that a proper biography should be written about David, so that his name alone doesn't become his entire legacy (like those of old heroes whose steles now serve as building stones) –

Your line will not fail. You know this. Yet memory surely will. Your sons – what will they remember? Or their sons, after? When all who knew you in life are but bleached bone and dust, your descendants, your people, will crave to understand what manner of man you were when you did these deeds, first and last. Not just the deeds. The man.When David then gives a list of three names for Natan to interview – that of his mother, an older brother, and his first wife – I thought, “Well, that's an intriguing way to fill in the historical record; flesh out the man.” But these interviews are completed by the first third of the book, and as the timeline then proceeds linearly (from the point when David spied Bathsheba bathing on a nearby roof – turns out I did know one more David story), the beginning felt like a misdirection. Two more complaints: Author Geraldine Brooks chose to use “the transliteration from the Hebrew of the Tanakh”, so a familiar name like “Solomon” becomes “Shlomo” and a familiar place like “Bethlehem” becomes “Beit Lethem”. With many characters and settings, this became confusing for a reader like me who isn't acquainted with such transliterations. And the second complaint is less trivial: If the point of Natan's project (and by extension, this book) is to understand King David as a man, seeing him through Natan's eyes makes little sense – we may see David's actions and reactions, but we never get inside his head. And at first that bothered me. But then I had an aha moment.

Brooks opens The Secret Chord with the only two known references to Natan (from the First and Second Chronicles, where he is known as Nathaniel). As King David has indeed had his biography recorded in word and art for the past three millennia, and as Natan's contribution has been limited to two lines, perhaps this is Natan's story after all; the story of a reluctant prophet in service to a mercurial ruler. Seen as Natan's story, this book makes perfect sense and I ultimately wasn't disappointed.

Geraldine Brooks is a master at filling in the gaps of history, at taking a fragment of a life and imagining it whole. Without florid or romantic language, she is able to set scenes that I find totally believable, and with The Secret Chord, I was transported to biblical times; led from olive grove to throne room to killing field. Ultimately, the abiding respect and affection that Natan has for David tells more about the storyteller than it does about his subject –

I have set it all down, first and last, the light and the dark. Because of my work, he will live. And not just as a legend lives, a safe tale for the fireside, fit for the ears of the young. Nothing about him ever was safe. Because of me, he will live in death as he did in life: a man who dwelt in the searing glance of the divine, but who sweated and stank, rutted without restraint, butchered the innocent, betrayed those most loyal to him. Who loved hugely, and was kind; who listened to brutal truth and honored the truth teller; who flayed himself for his wrongdoing; who built a nation, made music that pleased heaven, and left poems in our mouths that will be spoken by people yet unborn.

Funny that as often as I used to take the girls to Mass, and despite hearing Old Testament readings every week, I'm not all that familiar with the stories of David or Solomon or Moses or Abraham. Must not be a Catholic priority to study the early fathers.

For a while when we were still attending Mass, we had a guest priest. His name was Fr Kevin and although he had graduated from Seminary, he hadn't yet taken his vows. He was a young man, and with an Ichabod Crane physique and scarring acne, a homely man. When I, with the other parishioners, would line up after Mass to shake his hand and thank him for an interesting homily, he'd turn beet red and be unable to hold my gaze. There was something about his manner that made me think that he was struggling with attraction to women; to me, anyway.

But I did mean it when I said I thanked him for interesting homilies. Before coming to our parish, Fr Kevin had completed a tour of the Holy Land, and he was often able to add perspective to readings that were set there. I remember one week the Gospel was from when Jesus referred to himself as "the shepherd and the gate". Fr Kevin explained that when a shepherd would pen his sheep for the night in biblical times, it would be inside a stone-walled circle with a gap left at the entrance. Since wood was so scarce at the time, the shepherd would fold himself into that gap to sleep at night, becoming both the shepherd and the gate. Why would no one have ever told me that before? What a vivid image.

Even more vivid: One week the Gospel was about "it will be easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven". I've always thought that's a pretty extreme judgement, but it's beautiful in context. Fr Kevin explained that in the original walled city of Jerusalem, there were many gates. One of those gates was narrow, low, and almond-shaped, called The Eye of the Needle. Although a merchant would be unlikely to try to bring a camel through that gate, it could be done if the camel was unburdened of all it carried and led through on its knees. Imagine the rich man -- unburdened of his riches and down on his knees -- and suddenly the parable is a powerful metaphor. I can't believe I've only heard that explanation the once.

Ultimately, we were informed that Fr Kevin declined to take his vows and had returned to secular life. I had my private thoughts as to why that might be, but I hope that Kevin found a way to continue to teach. I think that Geraldine Brooks did a real service by turning to a biblical story this time -- no matter how secular we become in the west, Bible tales are as important to our social underpinnings as the writings of Plato; as culturally relevant as Shakespeare.