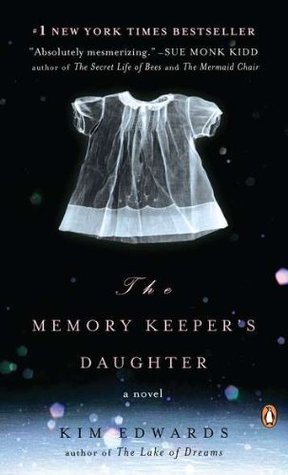

I picked up The Memory Keeper's Daughter at a book sale – seeing it there with the familiar cover, I recognised it as one of those books that everyone seems to have read, and with a decently high rating on goodreads, I marvelled that I hadn't read this book before; pleased to have added it to my purchase pile. At some point in this long life, I'm going to realise that being popular doesn't mean that a book is good. The Memory Keeper's Daughter just isn't very good, and at nearly 400 pages, it was with great impatience that I slogged through its overblown prose and inane plot. There will be spoilers ahead as I get specific.

The book begins with a sweet romance: love at first sight and a whirlwind courtship, within a year of meeting, David and Norah are married and expecting their first child. When Norah goes into labour during a freak snowstorm that prevents them from reaching the hospital, David, an orthopedic surgeon, is forced to deliver the baby himself at his clinic, with only the help of his nurse, Caroline. A beautiful boy, Paul, is delivered without incident, but then unexpectedly, another baby is coming: a baby girl who displays all the signs of Down's Syndrome. As this is 1964, standard procedure at the time was for such babies to be sent off to institutions to live out their short and pointless lives, and as David wanted to spare his wife the pain of watching their daughter eventually die, he sends the baby off with Caroline. When Norah comes around from her anesthetic, David tells her that there had been a second baby, but that she had been stillborn. What David doesn't know is that once Caroline arrived at the bleak institution and appraised its facilities, she decided to keep the little girl and raise her by herself in another city. This opening was intriguing and well written, but it's all downhill from here.

Much later in the book, when musing on his secret West Virginia upbringing, David thinks:

There was in the mountains, and perhaps in the world at large, a theory of compensation that held that for everything given something else was immediately and visibly taken away. Well, you've got the looks even if your cousin did get the smarts.Compliments, seductive as flowers, thorny with their opposites: Yes, you may be smart but you sure are ugly; You may look nice but you didn't get a brain. Compensation; balance in the universe.The book is told from four alternating points of view, and I think that this idea of yin-yang/balance/twinning was the central theme that author Kim Edwards was trying to explore, but it all just became so heavy-handed, repeated in all the different voices. David's younger sister died of a heart defect as a child, so he feared his daughter, Phoebe, would have the heart problems associated with Down's Syndrome – but where one died, the other lives; thrives even. David is disappointed that Paul, with his height and natural athleticism, won't play basketball, but as Phoebe grows, she loves shooting hoops on her driveway (and this fact is explored, over and over). Norah – who allowed herself to get tied down as a housewife – has a younger sister, Bree, who gets to live out all the Baby Boomer stereotypes (war protesting, free love, and eventually, Bree embraces the greed-is-good 80s). David and Caroline – the only two who share the secret that Phoebe lives – both have spouses who travel and are often away, but only one of the wandering spouses is unfaithful. And over and over, characters become aware of the interconnectedness of life, Norah through motherhood:

Slowly, slowly, as Paul nursed, as the light faded, she grew calm, became again that wide tranquil river, accepting the world and carrying it easily on its currents. Outside, the grass was growing slowly and silently; the egg sacs of spiders were bursting open; the wings of birds were pulsing in flight.This is sacred, she found herself thinking, connected through the child in her arms and the child in the earth to everything that lived and ever had.David, through his unlikely transformation into a critically acclaimed photographer (“Memory Keeper” was the brand name of his first camera):

I'm doing a whole perception series, images of the body that look like something else. Sometimes I think the entire world is contained within each living person.And Paul through his classical guitar playing:

Music is like you touch the pulse of the world. Music is always happening, and sometimes you get to touch it for a while, and when you do you know that everything's connected to everything else.And if the repetition of these big themes isn't annoying enough, small details are repeated and repeated: everyone has secrets and a yearning for freedom that builds “stone walls” between them; being upset makes people think they have a stone in their throats (and all of these stone metaphors, along with David and Paul collecting rocks and fossils together, probably has something to do with David's sense of shame over his father's dirt poor existence as a crook-backed miner); all babies have hands like starfish; everyone's shoulder blades are “delicate and sharp, like wings”; there are numerous wasps and trains and broken bones; and repeatedly musical notes are thought to become visible as they float through the air.

And then there are logical problems, like when Norah thinks, Had she been alone, even once, since Paul was born? But just a few pages earlier, Norah mused, Twice in the last month alone she'd hired a babysitter for Paul and left the house. That doesn't count as being alone? Or, would it really be possible for David to change his name based on a typo on his college admission forms (and become a doctor under the wrong name? Become married?) I didn't keep track of more of these inconsistencies, but they're in there. There are also countless, pointless mini-melodramas: a flirtation with alcoholism that goes nowhere; a fear of teenaged pregnancy that goes nowhere; a cancer scare that adds up to nothing; infidelity that's shrugged off. Most bizarrely is the late addition of a new character – a pregnant teenaged runaway that David wants to rescue – who adds absolutely nothing to the story but makes me want to insist: Can we never again have a character named “Rosemary” in a book with “memory” in the title? Pretty please you wacky Iowa Writer's Group authors?

In an afterword, Edwards states that the genesis of this book was a story that was told to her about a man who didn't realise that he had had a twin with Down's Syndrome until long after the twin had died in an institution. That would be an interesting story to explore, but so was what she did set up: how does a family get over the loss of a baby, especially when one of the parents knows that the baby never died? That is interesting, but it's not what Edwards wrote. In The Memory Keeper's Daughter, no one ever gets over anything, no one ever talks to each other, and it's frustrating to watch these unlikeable characters stewing in their own misery. Caroline is likeable as she fights the school board and the community to accept Phoebe, and I did appreciate some of what Caroline had to go through. But would a nurse in the 1970s, seeing that Phoebe was having a lethal allergic reaction, really turn to her panicking mother and say, “Are you sure you want me to get the doctor?” (Which has an echo later when it's revealed that David's family once overheard a grief-stricken mother say that God should have taken his sickly sister instead of her own healthy son. All the parallels, yeesh.) And speaking of unlikely prejudice, would Paul (who is supposed to be just a few years older than I am) repeatedly refer to Phoebe as “retarded” once he learns about her? This was in 1989, and I know I wouldn't have used that word then. Phoebe's journey could have been much more interesting if she wasn't just a cardboard bit player; not just there so that Paul can realise that he, who had every advantage, wasn't nearly as happy as his twin, who had to struggle for everything (and I think I've seen that movie and it was called Rain Man).

On top of all of that unexceptional plot, I just didn't like the writing.

For an instant, before the others turned, before Howard raised the bottle of wine and slid it into her hands, their eyes met. It was a moment real to only the two of them, something that could not be proven later, an instant of communion subject to whatever the future would impose. But it was real: the darkness of his eyes, his face and hers opening in pleasure and promise, the world crashing around them like the surf.But...The Memory Keeper's Daughter is certainly a popular book, and if you like any of these quotes, you might like the whole thing. 'Twas not for me.