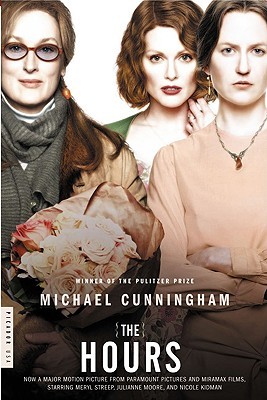

We live our lives, do whatever we do, and then we sleep -- it's as simple and ordinary as that. A few jump out of windows or drown themselves or take pills; more die by accident; and most of us, the vast majority, are slowly devoured by some disease or, if we're very fortunate, by time itself. There's just this for consolation: an hour here or there when our lives seem, against all odds and expectations, to burst open and give us everything we've ever imagined, though everyone but children (and perhaps even they) knows these hours will inevitably be followed by others, far darker and more difficult. Still, we cherish the city, the morning; we hope, more than anything, for more. Heaven only knows why we love it so.Something about The Hours seems so simple and obvious that anyone could have written it. There are three storylines, told from the points of view of three women over the course of three different days: We follow Virginia Woolfe on the day she begins to write Mrs. Dalloway in her English country home; we follow Clarissa in late 20th century NYC as she prepares for a party (her name and actions echoing those of the fictional Mrs. Dalloway); and we follow Laura, a 1950s LA housewife, as she attempts to find meaning in her domestic duties and steals a few hours to read Mrs. Dalloway. For source material, Michael Cunningham could rely on biographies and journals for the Virginia sections, on Mrs. Dalloway for the Clarissa sections, and apparently, the Laura sections are based on Cunningham's own mother. It all seems so simple and obvious, but of course it can't be or this kind of alchemy would happen all the time.

The Hours is total metafiction: Mrs. Dalloway is written and read and acted out in three different streams while characters muse on the insubstantiality of real life and the permanence of art -- and as each agrees that it's great literature that will survive the ages, I could never forget the fact that I was reading literature (and an attempt at greatness?). While the following was said by the doomed poet, Richard, it felt to me like both a mission statement and false modesty from the author himself:

What I wanted to do seemed simple. I wanted to create something alive and shocking enough that it could stand beside a morning in somebody’s life. The most ordinary morning. Imagine, trying to do that. What foolishness.And if that isn't all meta enough, we have Clarissa trying to catch a glimpse of Meryl Streep -- an actress she believes to have created immortal art -- and although I haven't seen the movie adaptation of this book, I can deduce that it was Streep who played Clarissa in the film (and obviously I can't lay this at Cunningham's feet, but the modern reader can't help but be reminded of the movie made of the book at this point -- and I wonder who Streep tries to catch a glimpse of?).

All of the characters are depressed to some extent (and Cunningham has said that he's a depressive) and nearly all of the characters are gay to some extent (and Cunningham is gay, but resents being called a "gay writer"), so was this an easy book for him to write? And if it was easy for this particular author, does that necessarily make it lightweight? I'm having such an ambivalent reaction to The Hours -- there are many lovely bits of prose but even I (no expert, though I have read the original) can recognise that Cunningham is echoing Virginia Woolfe's thesis and voice from Mrs. Dalloway -- but yet, that doesn't mean this book isn't also well written: and since it won the Pulitzer and the PEN/Faulkner awards, I feel the need to defer to their expertise as to the lasting value of The Hours.

As for my own reading experience (over which I do claim expertise), I didn't love this book (the goodreads criteria for four stars) but think it should rate higher than most of the books I've merely liked (three stars), so this rating should be considered a rounding up and not necessarily a glowing recommendation. *

But there are still the hours, aren't there? One and then another, and you get through that one and then, my god, there's another.

*And nothing but laziness is stopping me from implementing my own 10 point system of rating here to be able to make more subtle distinctions but I can't imagine going back and reevaluating what I've done so far: You do one and then another, and you get through that one and then, my god, there's another.