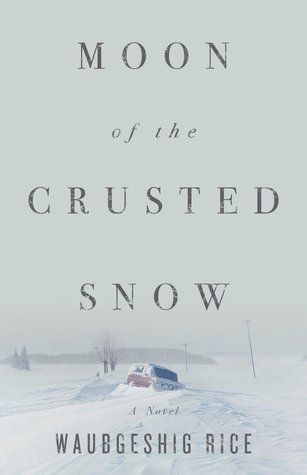

Moon of the Crusted Snow

He kicked up frozen shrapnel each time he raised a foot. A fine powder lay underneath. The conditions made him think of the specific time of year. There's a word for this, he thought, trying to remember with each high step across the hard snow. His knees raised as if to rev his mind into higher gear. He looked up to the lumpy clouds in the hope that the word would emerge like a ray of sunlight through overcast sky.

“Onaabenii Giizis,” he proudly proclaimed out loud. “The moon of the crusted snow.” His words fell flat on the white ground in front of him and he wondered which month that actually was.

Moon of the Crusted Snow is the third book I've read in the past year that looks at the collapse of Western society from a First Nations' perspective (along with Future Home of the Living God and The Marrow Thieves), with the difference this time being that we're watching a remote northern community grapple with the immediate aftermath of the phones and power going out, with no information getting through about what might be happening elsewhere. Inured to infrastructure failures on their reserve, at first folks are more annoyed than worried; but as news – and refugees – find their way into the community, these people need to start making decisions about the future. Told in rather unadorned prose, author Waubgeshig Rice has crafted a story more interesting than literary, but it does pose an intriguing question: If the lights all went out tomorrow, who would be better prepared for survival than those who have preserved some traditional knowledge? The corollary to that is, of course: And if the white people all started starving, where would they go to demand resources?

Nick and Kevin looked at each other. They were both nineteen years old, barely men. They had grown up in families that believed in teaching their kids how to live on the land and they knew how to hunt, fish, and trap. They knew the basics of winter survival. Those experiences had hardened their bodies and helped them mature, but they looked at each other now, fragile as small children. All that training could not have prepared them for what had happened.

What I liked best about this view of post-apocalypse reserve life is that there's a believable range of personality types. The main character, Evan, is a young father who had long ago determined to learn traditional knowledge from his Anishinaabe elders and pass it on to his own children. By contrast, his younger brother, Cam, has been content to collect welfare and spend his days smoking dope and playing video games. When the crisis becomes known, there are wise tribal counselors and hotheads, caregivers and deadbeats; and when a white survivalist finds his way to the reserve with an arsenal of guns and a secret cache of booze, he is able to attract some followers with his promises of easy living. For a community that was long ago stripped of its soul – forced to move off their traditional lands and then compelled to assimilate their children in the deplorable Residential School system – the collapse of the settlers' society just might be an opportunity for the Anishinaabe to rediscover their own ways.

Apocalypse. We’ve had that over and over. But we always survived. We’re still here. And we’ll still be here, even if the power and the radios don’t come back on and we never see any white people ever again.

Moon of the Crusted Snow has the heft of a YA novel – and for that reason, I think it would make an excellent teaching resource – and I was intrigued enough by the concept to spend the few hours it took to read this slim book. Ultimately, I think that the questions that Rice raised are more interesting than how he answered them, but I don't regret the time I spent in his world.