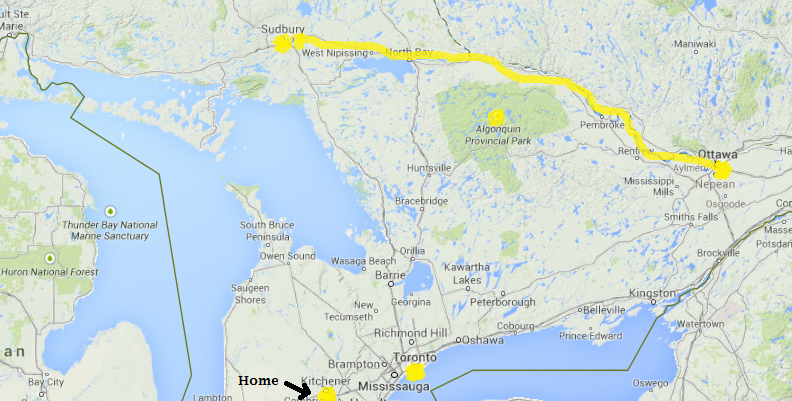

Even though I've lived in Ontario for more than half my life, I've never been to the famous Algonquin Provincial Park, north of Toronto. It has always sounded so remote, so far away, so wild. This is a place where my younger brother goes camping each summer with his pals; a place where they stand around the campfire stark naked because they know they will never see another soul. It shocked me, therefore, when last summer, as we drove west from Ottawa to Sudbury (the first time we had made this trip because I thought it would make an interesting stopover on the way home from Nova Scotia -- and it did!) I saw a sign pointing out the road to Algonquin to my left -- this meant that, unbeknownst to me, we were actually already well north of the wilderness and heading, um, norther. But even as we drove along and I accepted that the far and remote Algonquin Park was decidedly accessible, I knew that I would never propose a camping trip there: I am 100% afraid of each and every thing in the wild. And that was before I read The Bear.

In the preface to The Bear, Claire Cameron tells of a rare fatal bear attack that took place in 1991 in Algonquin Park. Despite taking all the necessary precautions, and also later discovering that the animal wasn't sick or starving and that the couple had vigorously fought back, two people were killed and eaten by a rogue black bear. Cameron was a camp counsellor at Algonquin at the time and based this story on both her memories of the event and later research, adding a couple of kids to the plot.

The bear attack opens the book, with the five-year-old narrator, Anna, and her nearly three-year-old brother Alex (nicknamed Stick or Sticky) tucked away in a tent for the night. Anna's childish, stream-of-consciousness voice describes the action throughout the book and the tension is heightened by the huge chasm between what the reader understands is happening and what the little girl thinks is happening (is that the neighbour's dog? Has he come to play?). I see a lot of criticism about whether or not Anna's voice reads as an authentic five-year-old and here is a typical scene, after her father has closed Anna into a metal Coleman cooler during the attack:

I am in the black. And I am mad at Daddy. He is shouting and pushing and both these things are naughty and I wonder if he is getting in trouble from Momma. When Momma gets mad she doesn't yell. She looks at me and lets the sad drip up from her heart through her veins and into her eyes. Her eyes send the sad into my eyes and then it drips back down into my heart and makes it feel like a ball. But not a ball that bounces up high -- one that is squishy because it needs Daddy to put in air. I won't ask Daddy to pump my heart because I'm so mad. I can't see him anymore. It is so so dark. I don't know if my eyes are open or shut and I put my finger to see. I can feel my eyelid. After I know then I open my eyes and it looks exactly the same. My eye feels sad.This is a typical scene because Anna, like a lot of five-year-olds, worries about getting into trouble, interprets everything through her own feelings, and uses all of her senses to explore her environment (she later sniffs her teddybear for comfort, describes tastes by "what kind of spicy" they are, and here can't tell if her eyes are even open until she feels her eyelids). Anna also has a vivid fantasy life -- conjuring castles and dolphins and magic dust -- so is it beyond her to imagine that her Momma "lets the sad drip up from her heart"? I also chose this scene because I see people don't buy that the Dad would have had the idea or time to grab each of his kids, separately out of their tent, and shove them into the cooler, latch it, and prop the lid open with a rock for air, all while, presumably, his wife is being savaged. (And while I would agree that it would have made more sense for him to have gotten everyone to safety in the canoe, this is a book, and this is the author's premise.) This scene is from page 13, so a reader can decide fairly early on whether to opt in or out from the journey, and I was certainly rewarded for opting in.

I loved everything about Anna and Sticky and believed that their adventure could have unfolded just as described. The fierce love/hate, protect/resent relationship that Anna had with her little brother was believable and well-written: you know these kids; they're every kid. The way that Anna's mind pinged between memories and present action was organic, and the fact that we are learning about her family dynamics through her own childish interpretations evokes empathy because, again, the reader understands what's going on better than the narrator herself (and especially regarding the parents' marriage). The plot was tense, and not just because of a bear: everything in the woods is a potential threat to a couple of preschoolers (don't eat those berries! Don't drink that dirty water!). I could almost complain that at 200 pages The Bear is too short to be weighty, but I wouldn't have found it as believable if the pair had been left to wander in the woods for days and days -- the story needed to conclude one way or another, and in the end, I was entirely satisfied. Actually, I was entirely gutted, and three *spoiler* scenes, including the final one, left me crying. I cried when the warden found the kids near death:

I put my head up and there is a man in the lake and he has a paddle in his hand and is sitting in the middle of a canoe. He is jumping out and bang on the canoe and his paddle throws onto the dirt and he makes a gaspy noise…The stranger's eyes are wide and I see that his mouth is like an O and he is rushing out of the canoe and his breath is almost huffy and I think he is mad and then I see he is crying from his eyes and his face is wet and he is trying to talk.I cried when Anna's Grandpa gives her a bath, singing just like he used to when he bathed her Momma, and he says, "Here I've been feeling sorry for what I've lost, and look at all I've got."And I cried at the end, where Anna and Alex have returned to the scene of the bear attack as adults and she lays down where she had last seen her dying mother:

And that's when I know that Mom could see us. If she was still conscious when she was lying here, and if her eyes were open, she would have seen me luring Alex into the canoe. She would have heard the clang when I threw the cookie tin into the boat. She would have caught sight of Stick's small body wriggling into the canoe. Maybe she saw that I got into the canoe after him and started to paddle with my hands. Maybe she knew that we got away.From start to finish, this book worked for me, and I am willing to accept that that is not a universal experience. To bring it back to my own brush with the wilderness that I began with: a waitress in Sudbury told us that on our way home we should take a detour to the small town of Killarny because its landfill is famous for the large numbers of black bears that scavenge there every day. As I had never seen an actual bear before (besides a flash of a cub on the side of the highway in Waterdown National Park years ago), I convinced the family to make the (longer than expected) detour. When we got to the landfill, there was a bulldozer working in the garbage, and as one might expect, the bears didn't show up that day. And so I still have yet to see a big bear, and after reading this book, maybe that's okay. This googled image is what I missed:

And if I could make a couple of minor complaints about the book: I understand an author needing to make her book have universal appeal (ie, Canadian writers shouldn't turn off potential American readers), but in such a Canadian book (when Anna understood she was looking at a beaver because it looked like the one in the aquarium at the Toronto Zoo, I knew exactly what she was talking about since I was just there in March) it bothered me that in the preface Cameron described Algonquin Park as "nearly three thousand square miles of wilderness situated two hundred miles northeast of Toronto". No one I know speaks of distances or areas in miles and I am going to assume that the author doesn't in her regular conversations either. And also, when Anna spends most of the book in saggy-bottomed ducky pyjamas, it bothers me that the little girl silhouetted on the cover is wearing a dress. Minor complaints, though -- I did love this book.