In 1986, my friend Kevin and I threw maple leaves on our backpacks and, with a few hotels booked and Eurorail passes in hand, made our way around Europe. While in Paris, we met a fellow traveller, Rob, who happened to hail from Australia, and over a modest dinner in a cozy café, we asked him about his homeland and we answered his questions about what it was like to be from Canada -- this was a time when Reagan was in his second term and, with the Iran-Contra stuff coming to light, the invasion of tiny Grenada, and his government trying to force our country to become a launching base for ICBMs against the USSR, we expressed the viewpoint common amongst our University-student friends: we were scared to death of America and lived in fear of the war-machine crouching just to the south of the longest unprotected border in the world. After a pleasant meal and discovering how much more we had in common with this Australian than with our North American partners, our conversation was interrupted by two quite beautiful young women and, standing with their backs to me and Kevin and addressing the Australian only, one of them said, "We have met many smart and friendly Canadians on our trip. Maybe one day you will, too." As these Americans strode haughtily out, I was mildly stung by the words that they had obviously rehearsed to put us in our place, but I remember spreading my hands in a gesture of explication and saying, "You see what bullies Americans are? They could have tried to join our conversation and correct anything we got wrong but they dropped a bomb and moved on." Our newfound friendship none the worse for wear, we continued to talk and discover all of the political and cultural commonalities we had between our two Commonwealth nations. After we left the café, I remember how we taught each other our national anthems and walked the cobblestoned streets of the Left Bank belting out, "Australians all let us rejoice, for we are young and free!" (And I should pause to say that I no longer fear America and wish Americans nothing but the best.)

|

| Me and Australian Rob |

That pet peeve aside, I was constantly amused during this book by the way that Bryson seemed to regard the Australians he met as an entirely different species -- whether describing them as merely quirky or "as mad as cut snakes", the strangest attributes of their culture were the ones which were simply the least American (like watching cricket or having a Parliamentary system of government with a Governor General) and again I was reminded of how compatible Kevin and I were with Australian Rob in Paris. Bryson's few stories about Australia's Aboriginal peoples were fascinating -- so often overlooked, these original inhabitants likely sailed to Australia ages ago (tens of thousands of years before any other peoples were braving the seas) with a viable breeding community and eked out a living in one of the most inhospitable landscapes on Earth, giving them the longest continuous culture in the history of the world. Without pottery or agriculture or iron tools or settlements, the Aboriginals thrived before European contact, but were hunted down and marginalised and had their children taken from them by the government "for their own betterment". That's such a shameful history (so similar to ours in Canada) that it's a pity that Bryson didn't attempt to talk to some Aboriginals to get their own perspective.

As for the humour, Bryson keeps his tone entertaining but periodically dips into the hyperbolic self-deprecation when talking about himself that I found so tiresome in The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid. A random example:

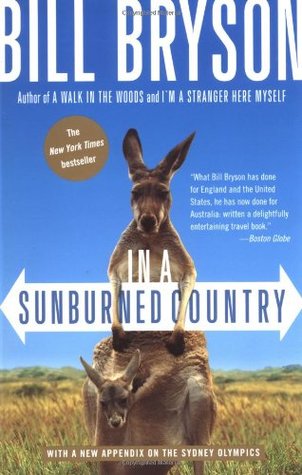

Dogs don't like me. It is a simple law of the universe, like gravity. I am not exaggerating when I say that I have never passed a dog that didn't act as if it thought I was about to take its Alpo. Dogs that have not moved from the sofa in years will, at the sniff of me passing outside, rise in fury and hurl themselves at shut windows. I have seen tiny dogs, no bigger than a fluffy slipper, jerk little old ladies off their feet and drag them over open ground in a quest to get at my blood and sinew. Every dog on the face of the earth wants me dead.If you find that funny, then you'll have no worries, mate (and if you don't, it doesn't happen too often). Overall, this was a light summer read that I hope Australians would agree shows off their country favourably (if one can forget that the ten most lethal creatures on Earth are all found there, it sounds like a lovely place to visit). And maybe it's an American thing, but Bryson concludes with the point that it's unfair that the rest of the world never thinks about, much less hears about, Australia. As this book was written before the Crocodile Hunter and the Wiggles became bona fide superstars, maybe he had a point, but this was also long after Crocodile Dundee, Midnight Oil, and "put another shrimp on the barbie", so who in the Northern Hemisphere didn't have some basic consciousness of the Land Down Under in 1999? Either way, it's a worthwhile note on which to conclude:

Australia is mostly empty and a long way away. Its population is small and its role in the world consequently peripheral. It doesn't have coups, recklessly overfish, arm disagreeable despots, grow coca in provocative quantities, or throw its weight around in a brash and unseemly manner. It is stable and peaceful and good. It doesn't need watching, and so we don't. But I will tell you this: the loss is entirely ours.I would give In a Sunburned Country 3.5 stars if I could, so consider the 4 a rounding up.

And on a more personal note, Australia always loomed large in my imagination because when I was a kid (9 or 10?) my Dad went there on a business trip. He was gone for 6 weeks, but for the longest time afterwards, I thought it had been 6 months -- either way, that's a long time to be without your Dad when you're a kid. I remember our home was pretty chaotic while he was gone (in an anything goes kind of a way) and also I remember not really liking it. I recall one night my Mom said she was woken up by a banging at the back door and, terrified, she went down to investigate (by herself but wondering if she should wake up Ken to go with her -- and he would have been 10 or 11 at the time). When she got to the main floor, she couldn't see anything, but the banging was even louder, and throwing open the door and turning on the light, she could see that the back gate was unlatched and, blowing in the breeze, it was swinging and pummeling the screen door (which, by the time Dad got home, looked like it had been kicked in). Kyler also reminisced to me once that he didn't think the grass was cut the entire time Dad was away, and he had enjoyed sitting in the front yard working on a go-cart, Dad's tools rusting away in the tall weeds beside him. I recall that there was an air of abruptness when Dad did return, like we didn't know he was coming that day; like we would have straightened things up if only we had known (Kyler remembers a scene about the grass and the tools, but since they didn't concern me, I guess I wasn't involved).

When Dad was settled in, he told us his tale about the flight to Australia on a two-storied jumbo jet, which was great until they hit an electrical storm over the Pacific and the hundreds of people on board all thought they were going to die...for hours. He showed us his snapshots (him holding a koala, him smirking from a hammock) and best of all, gave us souvenirs: the boys got boomerangs and I got a stuffed koala (very life-like and soft, and for some reason, not creepy because it was made of real rabbit -- not koala -- fur), and we all got t-shirts. Would it be saying too much about me to point out that I still have mine? Say too much about Daddy issues?

|

| Somebody Loves Me |

But does my Dad taking a trip there and me meeting an Australian 10 years later explain why I don't feel like Bill Bryson; like as though Australia would be the last place I'd ever think of? Or, since we're both Commonwealth countries, are Canada and Australia more connected? Hard to say, but Australia often comes up in conversations about ways we could improve the political/voting systems here. I've read quite a few books set there (especially by Peter Carey), probably because, until this year, Americans weren't eligible for the Man Booker literary prize, and as a result, Australian authors might have been over-represented before. In a Sunburned Country did have a lot of interesting information and helped to clarify some things I read in recent books (The Light Between Oceans and People of the Book in particular), so it was definitely a worthwhile read for me.

I really was interested in the information about the Aboriginals -- they don't come off too well; described by Euro-Australians as drunks and loafers. A teacher in a city states that once they get their welfare cheques, Aboriginal parents go off on a drunken walkabout, leaving their kids in the care of their teachers. A representative of a radio-based school for children in isolated communities says that very few Aboriginal children in the Outback participate because their parents are unable to read or write and help with lessons. Bryson himself observes that the Aboriginals he sees in Perth look homeless and beat up, every one of them having bandages or open wounds. A lawyer who represents Aboriginal interests says that there's obviously a racism problem when you don't see the marginalised group acting on TV shows or working in a factory or otherwise participating in the riches of Australia, and although Bryson agrees, he can also see that there's no easy way to fix things and he shrugs helplessly. What this made me think of was Thomas King's The Inconvenient Indian, where the author says that it's racist to assume that North American Natives even want to participate in our capitalist economy -- they should be left alone to find their own ways of living (but, one assumes, with money continuing to flow from government coffers). Is that what the Australian Aboriginals need? Are the welfare cheques (and the alcohol they can buy with the money) destroying the oldest continuous culture on Earth? I imagine the ingenuity these people had to survive for tens of thousands of years and I wonder if there's any way for them to recapture the dignity of that lifestyle (but it sounds cruel -- and obviously wrong -- to imagine turning Aboriginals out of the cities, cutting off government support, and telling them to go back to scratching out subsistence from the deserts). The answers are no easier in Australia than they are here in Canada, but I was intrigued by this article I read this week about the retirement of Australia's last Aboriginal police tracker -- what an encouraging blend of abilities and opportunity (and serves as proof that Australian news certainly does reach me, here, at the other end of the world).