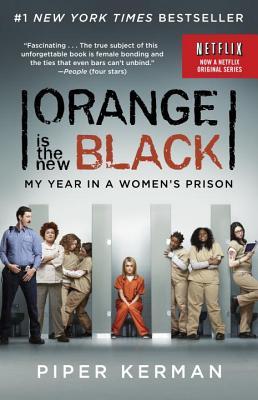

My husband and I started watching the Netflix adaptation of Orange is the New Black this past summer, and despite all the gratuitous sex and violence, we found it a little boring, and worse, we grew to dislike all of the characters (and are still on a hiatus from finishing it). Knowing that I was interested in the basic premise, my daughter bought me the book and I'm very glad she did -- not only is the real life story more interesting than the Hollywood version, but everyone, and especially Piper Kerman herself, comes across as better people.

First off, it should be noted that the author isn't actually a writer: In an interview included in the edition I read, Kerman tells how her editor kept urging her to relate to her stories more emotionally, to write as a "participant and not an observer", and I don't know if she 100% succeeded at that; the book is like a checklist of experiences with some googled prison facts thrown in. But this is a memoir, not a stab at literary genius, and I'm willing to accept it as the form Kerman chose to tell her own story, because it is an important one.

While on the surface Orange is the New Black could be taken as a fish-out-of-water story about a middle class white woman who has her youthful indiscretions catch up to her (ten years after the fact, Kerman is imprisoned for carrying a suitcase of drug money out of the country), the real value of this book lies in its social commentary: as the United States incarcerates more and more nonviolent offenders (the land of the free has 25% of the world's prison population, a 400% inflation since 1980), families and communities are broken down; and as prisoners are held by an indifferent system that provides them with no coping mechanisms for re-entry to society, the purpose of their imprisonment becomes unclear. I'll quote from Piper's epiphany at length:

Even when my clothes were taken away and replaced by prison khakis, I would have scoffed at the idea that the "War on Drugs" was anything but a joke. I would have argued that the government's drug laws were at best proven ineffectual every day and at worst were misguidedly focussed on supply rather than demand, randomly conceived and unevenly and unfairly enforced based on race and class, and thus intellectually and morally bankrupt. And those things all were true…The women that Kerman met at the federal prison in Danbury, the real life women who were kind and caring and generous, were so much more interesting to me than the cartoonish caricatures that Netflix put into the TV series. I am grateful that Kerman -- an educated woman with the skills and resources to expose what life is really like on the inside -- had this opportunity to observe and record (and I'm certain she's grateful that she spent the majority of her sentence in Danbury and not the Kafkaesque nightmare that was the Chicago Metropolitan Correctional Center). It's easy to have a tough on crime point of view when you don't have all of the facts about what the corrections systems looks like and I believe there need to be more conversations about what mercy and rehabilitation and justice really look like.

What made me finally recognize the indifferent cruelty of my own past wasn't the constraints put on me by the U.S. government, nor the debt I had amassed for legal fees, nor the fact that I could not be with the man I loved. It was sitting and talking and working with and knowing the people who suffered because of what people like me had done. None of these women rebuked me -- most of them had been intimately involved in the drug business themselves. Yet for the first time I really understood how my choices made me complicit in their suffering. I was the accomplice to their addiction.

A lengthy term of community service working with addicts on the outside would probably have driven the same truth home and been a hell of a lot more productive for the community. But our current criminal justice system has no provision for restorative justice, in which an offender confronts the damage they have done and tries to make it right to the people they have harmed. (I was lucky to get there on my own with the help of the women I met.) Instead, our system of "corrections" is about arm's-length revenge and retribution, all day and all night.

For further reading: Conrad Black's A Matter of Principle details his own misadventure with the American Justice Department, and like Piper Kerman, he left with a passion for exposing and improving what he found there; and Jeffrey Archer's A Prison Diary-- for anyone who thinks that Kerman sounds whiney and self-serving, take a look at Lord Archer's effort (*spoiler alert* He spends an awful lot of time worrying that his bottled water won't last until his next commissary day).

And while Orange is the new Black is an indictment of the American Corrections system, obviously much can be done about the state of affairs here in Canada. As a close correlation, I'll use this space to remember the Ashley Smith case, and in particular, the coverage as recorded by Christie Blatchford. Highlights:

Certainly, from the time I was regularly there, a couple of home truths were pretty clear.

The first is that the 19-year-old was a sad, seriously disturbed girl, only made sadder and more unhappy by prison.

Mentally ill — likely a borderline personality, a disorder very difficult to treat in the best of circumstances, that is, with a dedicated therapist and the dough to pay for it — Ashley became addicted to grotesque self-harming behaviour.

She “tied up,” as it’s called, multiple times a day with the homemade ligatures she stored in her vagina

Ashley wasn’t trying to commit suicide, but she found comfort both in tying up and in drawing correctional officers into her cell. The “physical handling” they often had to use to subdue her as they cut off the ligatures was all the physical contact she had with other human beings.

It’s beyond bearing, really, to contemplate the smallness of the life the young woman had.

She surely didn’t belong in prison.

The system can certainly handle what might be called the usual run of those with the usual mental illnesses, though it would be delightful if the Correctional Service of Canada spent more money hiring psychiatrists and psychologists who deigned to work 24/7, as guards and managers do.

But the seriously mentally ill, and inmates who hurt themselves, can’t be helped in a system which is understandably focused on security, and it is unreasonable to expect it to do so, just as it’s unreasonable to expect that police officers should be able to function equally well as social workers. They can’t, and saying they ought to is an exercise in let’s pretend...

The other thing that struck me is how marvelous were most of the correctional officers and some of the managers who were on the prison front lines, and had the most to do with Ashley, and knew and liked her best.

To the warden contingent at Grand Valley Institution for Women in Kitchener where she died, Ashley was a royal pain in the butt, sucking up resources, generating paperwork, and, most unforgivable in this nest of careerists, making advancement difficult.

But to the guards, the COs who actually cut the ligatures off her neck, she was a real person.

They should never have been asked to manage a girl as ill as she was, and they managed her imperfectly, but she was real to them. She mattered. That ought to count.