Danny's Song

(Loggins and Messina) Performed by Anne Murray

People

smile and tell me I'm the lucky one

And we've just begun

I think I'm gonna have a son

He will be like him and me, as free as a dove

Conceived in love

The sun is gonna shine above

And even though we ain't got money

I'm so in love with you honey

Everything will bring a chain of love

And in the morning when I rise

Bring a tear of joy to my eyes

And tell me everything's gonna be all right

Love a guy who holds the world in a paper cup

Drink it up

Love him and he'll bring you luck

And if you find he helps your mind, better take him home

Yeah, and don't you live alone

Try to earn what lovers own

And even though we ain't got money

I'm so in love with you honey

Everything will bring a chain of love

And in the morning when I rise

Bring a tear of joy to my eyes

And tell me everything's gonna be all right

And even though we ain't got money

I'm so in love with you honey

Everything will bring a chain of love

And in the morning when I rise

Bring a tear of joy to my eyes

And tell me everything's gonna be all right

And we've just begun

I think I'm gonna have a son

He will be like him and me, as free as a dove

Conceived in love

The sun is gonna shine above

And even though we ain't got money

I'm so in love with you honey

Everything will bring a chain of love

And in the morning when I rise

Bring a tear of joy to my eyes

And tell me everything's gonna be all right

Love a guy who holds the world in a paper cup

Drink it up

Love him and he'll bring you luck

And if you find he helps your mind, better take him home

Yeah, and don't you live alone

Try to earn what lovers own

And even though we ain't got money

I'm so in love with you honey

Everything will bring a chain of love

And in the morning when I rise

Bring a tear of joy to my eyes

And tell me everything's gonna be all right

And even though we ain't got money

I'm so in love with you honey

Everything will bring a chain of love

And in the morning when I rise

Bring a tear of joy to my eyes

And tell me everything's gonna be all right

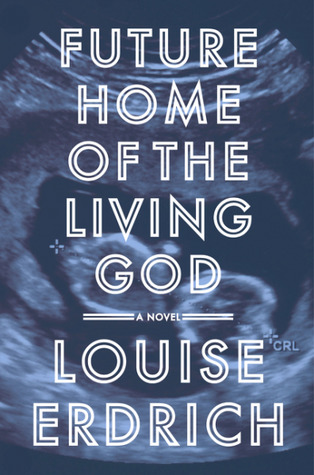

Not long after Dave and I moved back to Ontario with Kennedy, I was sitting in my parents' family room with my younger brother, Kyler, when out of nowhere he said, "Every time I look at you and Dave I think of Danny's Song. You know?" And then he started singing, "And even though we ain't got money, I'm so in love with you honey..." I was taken aback for several reasons: Kyler is not given to flights of romantic fancy; I wasn't crazy about having it pointed out to me that we had no money; and I thought it was presumptuous for him to assume he knew to what degree I was in love with my honey. I smiled after a beat, though, because it was a sweet and unprovoked statement, and while we didn't have money, Dave and I were not unhappy. In fact, at this early date, the future looked bright and sunny.

I have written before about how Dave was laid off while I was pregnant and that the job he had when Kennedy was born was not ideal, leading us to decide to sell our house, and how we gave our big dog away, and packed up our house to leave. I don't think I wrote before, however, that our parents were totally pushing for the move - both Dave's parents and mine said that we could live with them until we were on our feet; Ma said that my dad had several leads for Dave to get a decent job. I honestly didn't think that we'd be living with them for nearly a year, and if I had known that beforehand, I don't think I would have made the move.

As I wrote before, Dave and I had packed a shipping container with all our belongings at the beginning of December of 1995 and sent it off to London by transport truck. Meanwhile, Dave's father had cleared out his lower basement, and by the time our container arrived, we were there (along with my brothers) to unload and fill that room. We had sold, thrown out, and given away a lot of our belongings before the move, so when I found that most of our wood furniture had come through scraped and scratched, and cardboard boxes rattled with broken glass, this felt like a great loss to me.

Once we were in Ontario, my father didn't seem to have nearly as many job leads as my mother had thought, and while Dave did go on one interview, it didn't lead to a job (which made my Dad - who had employed that other man's shiftless son for years - quite angry and perhaps hesitant to set up anything else). We were staying together in London at first, but when Dave's friend Denton offered him a few weeks of work clearing out his farmhouse's dirt basement and pouring in a concrete floor, and Dave was gone all day and into the evenings, I decided to go stay with my own parents instead. I was pretty annoyed with Dave during this time - I wanted him to be out looking for a real job, but he was spending all his time with his old party buddy; Dave probably needed just this to make himself feel better, but I had a newborn, we were technically homeless, and I started feeling real despair at all I had lost.

In the end we had felt lucky to have sold our house at all in the depressed Edmonton housing market at the time (the boom would come just a couple of years later), so we didn't have much money in the bank, and the EI that Dave collected was mostly used up on diapers and other necessities for Kennedy. The EI itself wasn't going to last for very long, and when Dave read about an EI-sponsored program to take a few courses at the Ivey School of Business, he jumped at the opportunity - it would expand his hireability, and the pogey cheques would keep coming in so long as he was in the program. Dave was soon in school all day, doing homework all night, and he lived in London while Kennedy and I stayed in Burlington with my parents. I hated and resented this arrangement; I felt embarrassed and helpless. It went on for months.

Finally, after he "graduated" the next summer (both of our mothers remember this as Dave getting a Business Degree on top of his BFA; I don't correct them), my father gave Dave another lead - this time with a branch within the giant company Dad worked for himself - and Dave was hired as a lowest level sales guy with Maple Leaf Poultry. We couldn't have been happier, but with an office in the high-priced Toronto-adjacent housing market of Mississauga, we were distressed about how we were ever going to be able to afford even an apartment there.

After living between our parents' houses for nearly a year, and with both of my brothers (and one brother's new wife) also living at my own parents' short term at the time, my Dad was sick of having all his adult children underfoot, and he gave us a cheque for a down payment on a house - we were to find a real estate agent and get the hell out. Eleven months after we moved to Ontario, Dave and I weren't going to be homeless anymore, and for the first time in months, Danny's Song began to fit again.