Author Helen Macdonald is a poet, historian, life-long naturalist and avid falconer. When her father died suddenly on a London street, her reactions and the subsequent literary working through of her grief resulted in the unique and remarkable book, H is for Hawk. Her writing – poetic, literary, intelligent – moved me so much, that this review will mostly be in her own words. On learning of her father's death:

I was about to leave the house when the phone rang. Hop-skippety, doorkeys in my hand. 'Hello?' A pause. My mother. She only had to say one sentence. It was this: 'I had a phone call from St. Thomas' Hospital.' Then I knew. I knew that my father had died. I knew he was dead because that was the sentence she said after the pause and she used a voice I'd never heard before to say it. Dead. I was on the floor. My legs broke, buckled, and I was sitting on the carpet, phone pressed against my right ear, listening to my mother and staring at that little ball of reindeer moss on the bookshelf, impossibly light, a buoyant tangle of hard grey stems with sharp, dusty tips and quiet spaces that were air in between them and Mum was saying there was nothing they could do at the hospital, it was his heart, I think, nothing could be done, you don't have to come back tonight, don't come back, it's a long way, and it's late, and it's such a long drive and you don't need to come back – and of course this was nonsense; neither of us knew what the hell could or should be done or what this was except both of us and my brother, too, all of us were clinging to a world already gone.As a visiting lecturer at Cambridge, Macdonald was apparently able to free up her schedule, and her first reaction to the absence of her beloved father was to find a baby Goshawk and train it – which is essentially a 24 hour a day job for the first few weeks. Goshawks are notoriously challenging to train, and as she began her research and sourcing of her hawk, she remembered (and quotes at length from) the books she has read about them. In particular, Macdonald remembers a book – The Goshawk – by T. H. White, an author better known for The Once and Future King, the Arthurian legend which also contained Goshawks and Merlin the Magician who could shapeshift into a hawk. On meeting her baby Goshawk, Mabel, for the first time:

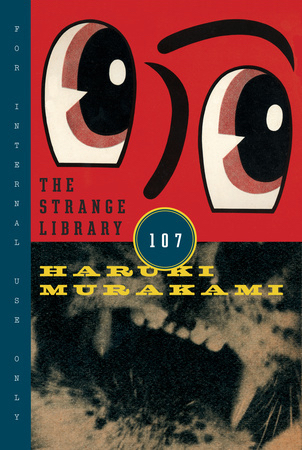

Two enormous eyes. My heart jumps sideways. She is a conjuring trick. A reptile. A fallen angel. A griffon from the pages of an illuminated bestiary. Something bright and distant, like gold falling through water. A broken marionette of wings, legs and light-splashed feathers.As Macdonald works through her grief by having a relatively easy time of training Mabel, she shares White's tortuous experience training his Goshawk, as well as his tormented biography: as a terrified and neglected child; a restless schoolmaster; a repressed homosexual and sadist; and as an ultimately unsuccessful tamer of Goshawks. Everything that Macdonald learns about White not only helps her to better understand the imagery he later put into his Arthurian books, but she can relate it to her own situation as well; to the way in which she was retreating from the human world into that of her Goshawk.

'Nature in her green, tranquil woods heals and soothes all affliction,’ wrote John Muir. ‘Earth hath no sorrows that earth cannot heal.’ Now I knew this for what it was: a beguiling but dangerous lie. I was furious with myself and my own conscious certainty that this was the cure I needed. Hands are for other humans to hold. They should not be reserved exclusively as perches for hawks. And the wild is not a panacea for the human soul; too much in the air can corrode it to nothing.H is for Hawk is a new slant on the introspective grief memoir – it includes elements of both the literary allusions of Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking and the back-to-nature vibe of Cheryl Strayed's Wild – and as a poet, Macdonald included some truly incredible imagery, which I savoured even when I didn't completely understand it (as when she said My heart is salt or The light that filled my house was deep and livid, half magnolia, half rainwater. Aren't those lovely if obscure?) And in the end, Macdonald made her peace with loss:

There is a time in life when you expect the world to be always full of new things. And then comes a day when you realise that is not how it will be at all. You see that life will become a thing made of holes. Absences. Losses. Things that were there and are no longer. And you realise, too, that you have to grow around and between the gaps, though you can put your hand out to where things were and feel that tense, shining dullness of the space where the memories are.I enjoyed H is for Hawk on so many levels – the hawk training in particular is totally fascinating – and I imagine it might speak most intimately to those who don't have the words of a poet to describe their own grief.

|

| Macdonald and Mabel |