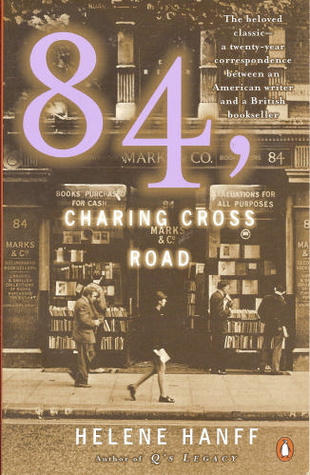

84, Charing Cross Road is a slim volume of correspondence between Helene Hanff, a NYC screenwriter (and collector of books), and the staff of Marks & Co., a second-hand bookstore in London, England. Covering the years of 1949 - 1969, this book not only demonstrates the quirky relationship between Hanff and her chief correspondent, Frank Doel, but it also deftly captures the time period that stretches from post-war food rationing to Beatlemania.

This is such a book of extremes -- Hanff chides and curses, all brash American whiskey-drinking-single-girl-living-in-a-cold-water-flat-with-a-weakness-for-antiquarian-essayists, and Doel responds with professional deference (not revealing until much later that, as copies of his letters went into the company files, he could behave no other way). And despite Hanff's frequent claims of being but a poor writer, she was able to send care packages of meat and other treats through a Danish mail-order company -- luxuries that were much appreciated by everyone in the office for the years that rationing was in place.

As others at Marks & Co. began their own correspondence with Hanff, it became obvious that she played a huge role in their lives and everyone begged her to come to London for a visit, but alas, the timing and financial situation was never quite right. As Doel himself wrote once, "One more summer will bring us every American tourist but the one we want to see". Not long after this, the letters become more infrequent, some of the staff move away and lose touch, and as the years go by, the long awaited visit never happens. Eventually, the planned meeting becomes impossible, and as I later learned, when Hanff finally did make it to London, 84 Charing Cross Road had been turned into a restaurant.

I was totally charmed and touched by this book -- on the one hand, it made me lament the loss of actual pen and paper correspondence, but on the other, it underscores how very lucky we are to live in a world where finding a like-minded person in a far away country has actually become easier. Perhaps that is no less special just because it has become less rare.

But I don't know, maybe it's just as well I never got there. I dreamed about it for so many years. I used to go to English movies just to look at the streets. I remember years ago a guy I knew told me that people going to England find exactly what they go looking for. I said I'd go looking for the England of English Literature, and he nodded and said: "It's there.”

Edit from August 7th

This book must have been on my mind for the past week. This is the conversation that I had this morning with my own long-distance correspondent, the lovely Darlene from Texas:

Me: I dreamed about you last night. For some reason I was in Texas and just as I was checking out of my hotel, you called my cell and invited me to visit. I said sure and you directed me to a bus stop. When I got on the bus, it was like from the Third World (rickety, over-crowded, plank seats) and we were driving forever down a narrow, cracked highway. I called you and asked repeatedly, "Are you sure this is the Interstate?" and you kept reassuring me it was. Suddenly, the bus pulled up to a dusty old building in the middle of nowhere and as the bus driver left, people were shouting out, "Do we get off? Is this the stop? Is this even a bus?" And then I woke up. Shall we analyse that like a literary exercise or brush off the psych texts?

Darlene: What a great dream! We could do either. Obviously, you really WANT to visit me in Texas. Yet, it is Texas, and those images of dust and cowboys are hard to shake, and you probably have hidden reservations about what to really expect, lol. To ease your mind, the Katy freeway in Houston is 26 lanes in sections (if you count the frontage roads) giving it the distinction of the widest road in the world. =) Come on down! =) xox

Darlene: Along the same lines, whenever we are out of the country and people ask us where we're from, we never say the U.S. We say Texas (imagine that, but it's a Texas thing). Invariably, they want to know if we have a horse...

Me: When I woke up, the part I remembered most was, "Is this really the Interstate?" because even I've seen the roads in Houston. I wonder if I was worried about having been driven across the border into Mexico, by mistake or by mischief? I wonder if it's one of those dreams (where you think you need to pee but there's something wrong with all of the toilets and that prevents you from wetting the bed) where something doesn't happen because it subconsciously scares you? Like, what if we met each other and we were bored with each other and immediately regretted it? And do you have a horse?

Darlene: If you visit me, you're far enough from the border to not have to worry about abduction or cross-border violence. As far as the dream, what you've seen on TV could very well have influenced that, and parts of the border do look very similar to the landscaping of your dream. I'd say that's a definite possibility of interpretation. Somehow, while I know it's a possibility, I don't think I'd be bored of you at all if we met. There's so much common ground that I'd find to talk with you about such as issues of religion, children, stay-at-home Mom issues and the empty nest (you're almost there sister) that I think all those things would serve as a bridge to closer friendship. We have much in common. Susan is the one that I love online, but am not so sure about meeting in real life. I have no idea what we'd really have to talk about. While I enjoy the relationship we have, our lives are very different. And, no, I don't have a horse, lol.

Me: I think we would get along just fine if we met (and I don't actually have any fears about being carried off across the border, lol) but if I had to amateurishly analyse the dream, that's what I've got. I read a book last week (84, Charing Cross Rd) about a single-woman screenwriter in NYC who had a correspondence with a second-hand bookshop in London, England from the 1940s-60s. They became closer and closer and the Brits kept begging her to visit, and they wrote each other about everything in their lives, and then time went by and people left the store and lost touch and the woman never made it to England and the letters became less frequent and then her chief correspondent died, and by the time she FINALLY made the trip, the site of the bookstore was a restaurant (sorry if you've read the book and this is all old news to you). It's a true story and obviously made me think of you and Susan -- remember when we used to know everything about her, too? How does that grow and then fizzle out? How do you stop it? What if the screenwriter had made that trip to England and no one was as clever or as genuine as they seemed on paper? Upon reflection, this is probably where the dream came from. As for meeting Susan, I bet it would be a lot of fun -- but what if she actually smokes dope like the jokes she likes to post on facebook? I'd be aghast! Lol. And too bad about the horse. =D

Darlene: Sounds like a great book. I need to put it on my "To Read" list. Susan would be a lot of fun but I don't drink and party like I used to. That all kind of stopped in 1990 when I got pregnant, lol. I can't promise you clever, but I can promise you genuine. What you see is what you get. By no means am I a boring fuddy-duddy (okay, maybe a little boring) but my wild days are over. And if you do come, I'll find you a horse. =D

Me: Well, I'm also a little boring anymore, but no more so than what I type. =D

And talk turned to other things...First of all, how nice is it to have someone who will talk about your dream with you? Darlene and Susan and I met on Neopets (of all places) 7 or 8 years ago now, and as it says here, we were the three amigas; the closest friends that internet strangers can be. And how different we are! Darlene is a Texas Republican and Susan is a Michigan Democrat and it was a wonder to me to see them debate so politely during the Bush and into the Obama years -- really fascinating to a neutrally observing Canadian.The two of them stopped playing Neopets at about the same and we moved our friendship over to facebook (where we finally saw pictures of each other -- amazing!) and we remained tight for a while. Eventually, though, Susan stopped including us in everything, and although Darlene and I talk daily (especially through playing Words With Friends) we're not as close to Susan anymore. This long-distance friendship arc is what I saw being played out in the book and, I suppose, it spilled over into my dreams. I would love to visit Darlene someday (and actually think it would be a blast to include Susan, too -- she's a big-hearted, smart-mouthed ball of fun) but it would be pretty awkward to casually mention to Dave at this point that the friends I have been closest to in the world for the past few years are on the other end of a computer screen (and to have to explain we met on a children's gaming site...shudder). These are the women I was thinking about when I wrote above: It underscores how very lucky we are to live in a world where finding a like-minded person in a far away country has actually become easier. Perhaps that is no less special just because it has become less rare.