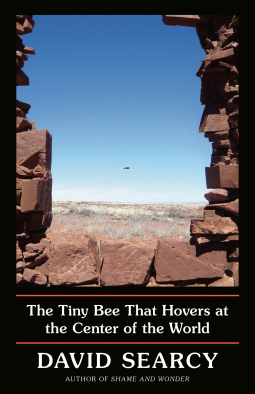

She points. A tiny bee floats in that empty, ruined space. It’s absolutely still. It holds that space in place the way some hovering insects do as if obedient to, in reference to, some universal center. I can’t see it in my camera. “Higher, up, up, get it please.” She wants that bee. She’s almost frantic. There. I show her. Zoom it in. And there it is — in focus even, perfectly still within the empty, ruined window of the Meteorite Museum on the ruins of the road through our subconscious, in the middle of the world and on and on as far as you like, on out as far as there are references. A dream of perfect stillness. I believe I’ve never seen her quite so happy.

The publisher of The Tiny Bee That Hovers at the Center of the World suggested I might like to read this, based on some of my past reviews, and so I downloaded an ARC without really looking too hard at what it is. And now that I’ve read it, I’m finding it pretty hard to describe just what this is: More one book-length essay than a collection of related essays, author David Searcy writes of the past, present, and future, the personal and the public, circling back to ideas, foreshadowing events that won’t be revealed for many chapters, finding meaning in the gaps and ellipses and those things that can only be glimpsed when we don’t look at them directly. In a later section, Searcy describes a project he had assigned himself — to view Mars nightly from his homemade backyard observatory and to make an inkwash drawing of what he sees, without thinking too much about it — and that’s what this entire book feels like: The eyes squinting skyward while the hand describes a circular smudge and meaning found in the distance between these acts. This is art, and as a reading experience, I was engaged and always interested in Searcy’s experiences, but can’t say that I always understood what he was making of it; but isn't that just like any art? (Note: I read an ARC through NetGalley and passages quoted may not be in their final forms.)

I love concentric tales. The drawing of the drawing or the drawing of the photograph. The stories drawn within each other — once you let the artifice become the ground, the whole idea of ground becomes the story, the excuse, and you can just keep on like that. Each tale, impression, becoming, as in The Thousand and One Nights, a ground, a desert even insofar as it permits that emptiness, that deep discontinuity between the layers. Exactly as the self gives up to find itself again, the meaning seems to arise in the gap, the glance away. A case, I hope, for being “scattered.”

As an example of the formatting: The book begins with Searcy and his partner taking a trip to the once futuristic Arcosanti molded concrete hive community in the Arizona desert (and this chapter references, among many other ideas, the Lowell Observatory and Percival Lowell’s mistaken identification of canals on Mars), to a brief chapter describing the struggle of encouraging a small child to stay still long enough to look through a telescope, to a meditation on photography (which introduces a vintage photograph from the author’s mother’s collection, depicting a little girl on a swing who sounds an awful lot like the little girl imagined in the previous essay). Arcosanti, Lowell, Mars, and that photograph will be referred to again and again throughout the book — stories within stories; concentric tales — and despite all these impersonal details making up the bulk of The Tiny Bee, the whole serves as a revelatory and thoughtful memoir.

The photographic process is so passive, so inevitable you’d think there must be similar, simple, natural intuitions, revelations all around us all the time. You think of shadows, mirrors, fossils. But these things, one way or another, do not separate from everyday experience — they’re not still or they’re not passive or not flat. They move with us. We move around them. Or they join the world’s activity as projections. They don’t fix and represent our observation. Even mirrors do not hold our looking up to us like that. If there were something like a photograph then it would be a photograph. A thing resembling knowing would be knowing.

This seems to be a book about emptiness — Searcy frequently invokes alleys and vacant lots, the “kindergarten-landscape gap between the earth and sky”, the vacuum he imagines is at the center of living things — but he fills the empty spaces with nuance and significance. I still don’t know if I have satisfactorily explained what this book is, but it is the story of a life and all life; a piece of art that engaged me and that definitely made it worth my time. Rounding up to four stars.