This is the excellent foppery of the world, that,

when we are sick in fortune – often the surfeit

of our own behavior – we make guilty of our

disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars: as

if we were villains by necessity; fools by

heavenly compulsion; knaves, thieves, and

treachers, by spherical predominance; drunkards,

liars, and adulterers, by an enforc'd obedience of

planetary influence; and all that we are evil in,

by a divine thrusting on: an admirable evasion

of whoremaster man, to lay his goatish

disposition to the charge of a star!

King Lear (I.2.115-125)

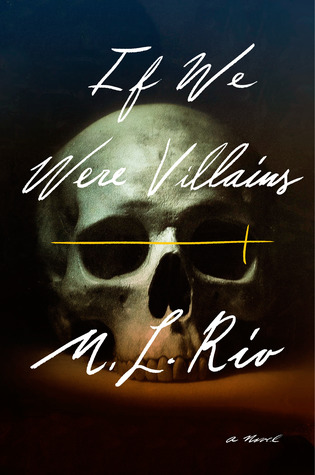

My daughters were both “theatre kids” growing up, as was my husband when I met him (he went on to get an acting degree from an exclusive program, much like the one described in this book), so I approached If We Were Villains, with, perhaps, an above-average degree of interest in, understanding of, and patience for the quirky insecure-extrovert, everything “felt twice”, shout-it-out-loud, trembling egos and tight-knit community of budding actors. Totally open to whatever author M. L. Rio – herself a graduate of an elite degree in Shakespeare Studies – decided to set in this world, I was, nonetheless, not blown away by this story. A strange hybrid of the plot of Donna Tartt's (much better) The Secret History and the structure of Frank Abagnale's Catch Me If You Can, other than some of the nicely atmospheric scene-setting involving the fairytale campus, nothing about the writing here was engaging or artful. Ultimately disappointing for me, I could have given this one a pass. Three stars is a rounding up.

Panic flutters softly around my heart. For a moment I'm twenty-two again, watching my innocence slip through my fingers with equal parts eagerness and terror. Ten years of trying to explain Dellecher, in all its misguided magnificence, to men in beige jumpsuits who never went to college or never even finished high school has made me realize what I as a student was willfully blind to: that Dellecher was less an academic institution than a cult. When we first walked through those doors, we did so without knowing that we were now part of some strange fanatic religion where anything could be excused so long as it was offered at the altar of the Muses. Ritual madness, ecstasy, human sacrifice. Were we bewitched? brainwashed? Perhaps.As the book begins, Oliver Marks is reaching the end of a ten year prison sentence when he receives a visit from the cop who put him away: Detective Colborne is about to retire and he asks Oliver if he's finally ready to tell the truth about what really happened on his college campus all those years ago. After securing a promise from Colborne that everything he says will stay between the two of them and have no consequences for anyone else involved (because that would be a legally binding agreement between cop and con), Oliver begins to tell a detailed story of the tragic events that occurred in his fourth year in an elite acting program. The book is divided into five Acts (each Act preceded by a Prologue that follows Oliver and Colborne in the present; each Act then divided into Scenes), and the narrative follows the familiar plot development of a Shakespearean play. Villains is technically a mystery: there's no hint in the beginning of why Oliver was incarcerated, and even after a crime does occur in the retelling, it takes the entire novel for him to explain what happened. I was interested to see the mystery elements play out, but they weren't particularly well executed in the end.

What Rio knows, and what she writes about well, are the hearts of young actors and the melodramatic dynamics at play between a cloistered group of them (even if each of the seven fourth-years are cliched types: the hero, the vamp, the sidekick, the ingenue). For the most part, I liked the detailed descriptions of the performances they put on (Macbeth's witches by the lakeside on a dark Halloween night, scenes from Romeo and Juliet at a Christmas masked ball), but some of the longer scenes from rehearsals – where the characters recite pages straight from the Shakespeare scripts – seemed to go on too long; it feels lazy. And for those who think it's corny that these actors all like to quote Shakespeare to one another in ordinary conversation, Rio makes similar caricatures out of all the college's students:

We sat on the left side of the aisle, in the middle of a long row filled in by second- and third-years. The theatre students, always the loudest and most likely to laugh, sat behind the instrumental and choral music students (who kept mostly to themselves, apparently determined to perpetuate the stereotype that they were the most complacent and least approachable of the seven Dellecher disciplines). The dancers (a collection of underfed, swanlike creatures) sat behind us. On the opposite side of the aisle sat the studio art students (easily identified by their unorthodox hairstyles and clothing perpetually spattered with paint and plaster), the language students (who spoke almost exclusively in Greek and Latin to one another and sometimes to other people), and the philosophy students (who were by far the weirdest but also the most amusing, prone to treating every conversation as a social experiment and tossing off words like “hylozoism” and “compossibility” as if they were as easily comprehensible as “good morning”).As for the writing: I didn't much like the perpetual parenthetical asides, plot details weren't credible to me, characters' motivations were inscrutable, and Rio has a penchant for choosing words that I don't believe would have been those used by Oliver in recounting his story to the detective – yes, he is a self-proclaimed lover of words, but I don't think anyone would say, “The water lapped at his nose and mouth and left a cloud of dark hematic red around his face”; and most people wouldn't even know the right term to describe closing a padlock as, “I pushed the shackle toe into place without hesitating”. The love stories were hammy, the peek into Oliver's homelife was pointless, and the ending grated on my nerves; I didn't believe any of it. Even so: there were enough nicely captured bits of the life that were recognisable to me that I'm tempted to pass this on to the daughter who went on to get an acting degree; she just may have been a villain, too, had the moon and stars so compelled her.