Tita was literally "like water for chocolate" – she was on the verge of boiling over. How irritable she was!

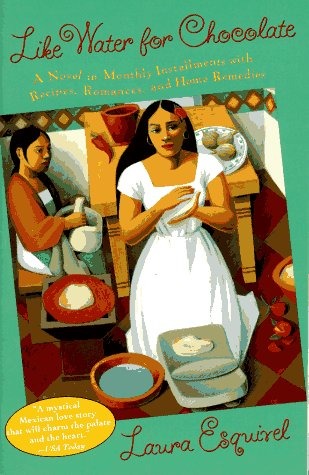

Like Water for Chocolate was my book club's pick, or else I likely wouldn't have picked this up on my own. And as much as it didn't knock my socks off, I'm not unhappy to have read this: author Laura Esquivel makes some interesting choices in the writing of this telenovela-like magical-realism romance and it brought some not unwelcome diversity to my notion of “the novel”. My biggest complaint: Since this is essentially a romance, I wish I could have cheered for the central romantic union; but Pedro never seemed worthy of such a strong, resilient, desirable character as Tita, and that annoyed me throughout and in retrospect.

His scrutiny changed their relationship forever. After that penetrating look that saw through clothes, nothing would ever be the same. Tita knew through her own flesh how fire transforms the elements, how a lump of corn flour is changed into a tortilla, how a soul that hasn't been warmed by the fire of love is lifeless, like a useless ball of corn flour. In a few moments' time, Pedro had transformed Tita's breasts from chaste to experienced flesh, without even touching them.¡Ai, caliente! As the youngest daughter in a traditional Mexican family at the turn of the twentieth century, Tita De la Garza has been informed by her tyrannical mother, Mama Elena, that it will be Tita's duty to forswear love and marriage and take care of her mother unto death. When a young man, Pedro, and Tita fall in love at first sight, Mama Elena refuses to condone their relationship – offering instead her eldest daughter, Rosaura, for marriage. In order to stay close to Tita, Pedro agrees to the arrangement, and thus begins two decades of the pair living in the same house; secretly burning for one another while Mama Elena and Rosaura scheme to keep them apart.

The narrative is told in twelve chapters that follow the months from January to December – while skipping ahead days, weeks or years at a time – and each chapter opens with a recipe that Tita (as the overworked cook for the family's ranch) is preparing in the text of the chapter. I liked the way that each recipe was thematically related to what was happening in the story, and that while the cookbook-like descriptions of recipes are suddenly interrupted by the narrative's action, they would always be picked up again in the text:

Drying her tears, Tita removed the pan from the heat herself, since Gertrudis burned her hand trying to do it.In a time and place where women (and particularly youngest daughters) had little agency, it was satisfying to see what power Tita wielded through the food that she prepared. Further, bringing in elements of magical realism, Esquivel ensures that Tita's suppressed emotions are released into the food she cooks – and that seems a fitting revenge for someone chained to the kitchen, denied a voice.

Once the custard is cool, it is cut into small squares, a size that won't crumble too easily. Next the egg whites are beaten, so the squares of custard can be rolled in them and fried in oil. Finally, the fritters are served in syrup and sprinkled with ground cinnamon.

While they let the custard cool so it could weather the storm to come, Tita confided all her problems in Gertrudis.

I get that the power plays between the women of the De la Garza household are a mirror of the Mexican Civil War that is referenced as ongoing in the background at the same time – with Tita and her freedom-fighting sister, Gertrudis, acting as the rebels against the dictatorial traditionalism of Mama Elena and Rosaura – but if this is meant as a work of feminist rebellion (as I believe it is), it's not quite satisfying enough to have Tita fighting for a traditional domestic role with Pedro, or that she would turn her back on a more intellectually stimulating match with the local doctor because Pedro makes her burn; for years. And for a book that so closely relates the steps to recipes as diverse as a wedding cake, matches, and tooth powder, I was underwhelmed by the skimming over of what seemed like major events:

Chencha figured this lie would cover her with glory, but unfortunately she wasn't able to tell it. That night, when she got to the house, a group of bandits attacked the ranch. They raped Chencha. Mama Elena, trying to defend her honor, suffered a strong blow to her spine and was left a paraplegic, paralyzed from the waist down.Filled with interactive ghosts, alchemical transformations, and a fantastical ending, Esquivel follows in the tradition of other Latin American writers of magical realism – and like I've said before, this is a genre I don't quite connect with. Although it's the men like Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata who are remembered in the history books from this time in Mexico, I do appreciate that Esquivel brings in the women's stories; assures us that Tita “will go on living as long as there is someone who cooks her recipes”. I just wish she didn't throw her life and love away on the undeserving Pedro. Looking forward to book club. Three stars is a rounding up.

Further thoughts after Book Club: I wasn't able to attend the February meeting at which this was picked (I was at the Bowie Tribute concert instead), so while I had heard that Like Water for Chocolate was suggested by a couple of members who think of this as their favourite book, I had forgotten who they were by the time this month's meeting came around. And not having loved the story, and not wanting to hurt anyone's feelings, I decided that I would be generous in my statements. Side note: At one point in the month, I suggested on the Facebook page that we should make recipes from the book to bring to book club, but once we all started reading it - and saw that the recipes involved boiling pigs' heads and baking cakes made with 170 eggs - that idea was soon forgotten. (But I did make and bring Spicy Mexican Hot Chocolate Cookies. ¡Ai, caliente!)

So, wanting to not look a jerk, I sat back with my wine and cookies (and soup and tortillas and chickpea salad and brownie; for the first time since I joined boot camp, I had a little bit of everything), and let others do most of the talking. Nat said that she thought of it as a "telenovella-Cinderella" (which wasn't far off my overall description), and she decided to take the fantasy bits in the vein of the movie Big Fish; that they were simply an exaggerated storytelling style. And then Carrie said that she liked the magical realism parts the least of all, and Pat - who is someone else's Mom and was the oldest member there this week; not afraid to tell it like it is - argued that she doesn't think that any of it is meant to be taken seriously; she thought the book was a comedy and she laughed her head off at every ridiculous thing that happened. Now, I may not "connect" to stories with magical realism, but I'm enough of a snob to want to respect it as a literary device, so that's when I redirected the conversation with my observation that the women in the family were a microcosm of the Mexican Civil War playing out in the background, and that led to an interesting conversation about tradition vs revolution (and especially Tita's desire for but lack of action regarding rebelling against her mother).

And then we talked about the love story - why would Tita wait twenty-two years for the wimpy Pedro when she could have had a modern and intellectually stimulating life with the doctor? And that's when I realised that my "microcosm" observation needed to include the men as well: It now seems obvious to me that Mama Elena and Rosaura represented the traditional and the dictatorial, Gertrudis was the rebel (like Pancho Villa), but Tita was all of the Mexican people caught in the middle. Looking at her situation from twenty-first century Canada, it's probably condescending and ethnocentric of me to regard the (white American) doctor (representing modernisation for the Mexican people) as the obvious choice when of course Tita would feel the pull of Pedro and the traditions and safety that he represents. By waiting for Mama Elena and Rosaura to die before they officially got together - by making sure that Esperanza was safely married (to modernity and not beholden to her mother's care) - Tita marched into the future by evolution rather than revolution. I left the meeting liking this book so much better, having learned from everyone there. That's a great feeling.