As the borders between night and day stretch to their thinnest, so too do the borders between worlds. Dreams and stories merge with lived experience, the dead and the living brush against each other in their comings and goings, the past and the present touch and overlap. Unexpected things can happen. Did the solstice have anything to do with the strange events at the Swan? You will have to judge for yourself.

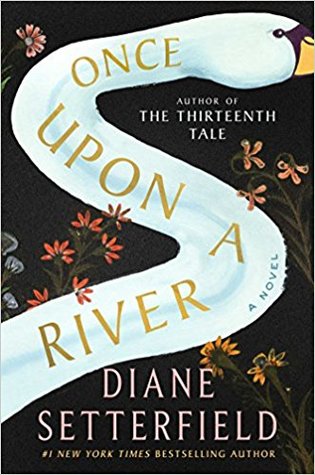

Once Upon a River has so many elements that I found attractive – a central mystery with otherworldly overtones, strong characterisations, storytellers meeting by a fire to practise their words and rhythms – and the time and place were intriguingly captured – alongside a river “which is and is not the Thames”, at the end of the nineteenth century where science and superstition intertwined – and yet, something about this book didn't completely click for me. I enjoyed author Diane Setterfield's writing – from the delightful word choices to the overall plot and its resolution – but I can't put my finger on why this wasn't a slamdunk for me. I am intrigued enough to want to go back and read Setterfield's previous books. (Note: I read an ARC and passages quoted may not be in their final forms.)

The remote riverside communities that these characters inhabit is a rough and tumble place – with constant cold and damp, hunger and beatings and the disposal of unwanted children – and despite some very menacing scenes, Setterfield's tone can be funny and generally ironic:

There were some for whom the world was such a tricky thing that they marvelled at it without feeling any need to puzzle it out. Bafflement in their eyes was fundamental to existence. Hix the gravel-digger was one such. His pay, which was enough on Friday night to last the week, was generally gone by Tuesday; he always owed for more pints of ale at the Swan than he remembered consuming; the wife he only beat on Saturday night – and not always then – ran off for no reason at all to live with the cousin of the cheesemonger; the face he saw reflected in the river when he sat glumly staring into it with no bread in his belly, no ale to dull the hunger and no wife to warm him, was not his own but his father's. The whole of life was a mystery, if you delved even a little way under the surface, and causes and effects not infrequently came adrift from each other. On top of these daily bewilderments, the story of the girl who died and lived again was one he drew consolation from as he marvelled at it, for it demonstrated conclusively that life was fundamentally inexplicable, and there was no point in trying to understand anything.As the story begins, a stranger staggers into the Swan – the pub known for storytelling; if you're looking for a place to dance or brawl, there are other options – and in his arms he's holding a little girl who has obviously drowned. But as the man's injuries are attended to, the girl comes back to life; and while it turns out that the man is not her father, three other families will eventually come forward to claim her as their own. So is this little girl, who cannot speak and who makes no preferences known, actually Amelia, Alice, or Ann? Or, since she appeared at the “thin time” of the winter solstice, has she crossed over from somewhere else?

I did like that Setterfield set her story in the Age of Discovery – locals both discuss Darwin in the pub and accept that a nearby village was attacked by dragons in living memory – and my favourite character was probably Rita: a nurse/midwife who knew that the little girl had no vital signs when she first appeared, so she conducts experiments to find an explanation. In addition to a few brutes and criminals, there are many upstanding characters trying to ensure that the little girl goes to the right family, and I couldn't decide if it was appropriate or patronising to have the only person of colour be a large Black man who is perfectly patient, wise, forgiving, loving; educated, rich and hard working; the ideal father and husband, with a gift for communicating with animals. Robert is so much better than everyone else, in every way, that he somehow didn't seem like a real person to me, which I assume wasn't Setterfield's intent (and which comes off as a bit condescending). And always and everywhere, dampening the air and seeping through the cracks, is the character of the river itself:

He had woken the river now; its current took hold of him. Water in his mouth. Moonfish in his head. Knowledge: a mistake. He groped for the surface; his hands met trailing, floating plants. He grasped to haul himself up, but his fingers closed on gravel and mud. Flailing – twisting – the surface! – gone again. He took in more water than air, and when he cried for help – though who had ever helped him, was he not the most betrayed of men? – when he cried for help, there were only the lips of the river pressed to his, and her fingers pinched his nostrils shut.In a way this reminded me of The Luminaries, but better; but still not great. I wish I liked it better.