He takes in the hundreds of new prisoners who are gathered there. Boys, young men, terror etched on each of their faces. Holding on to each other. Hugging themselves. SS and dogs shepherd them like lambs to the slaughter. They obey. Whether they live or die this day is about to be decided. Lale stops following Pepan and stands frozen. Pepan doubles back and guides him to some small tables with tattooing equipment. Those who have passed selection are guided into a line in front of their table. They will be marked. Other new arrivals – the old, infirm, no skills identified – are walking dead.

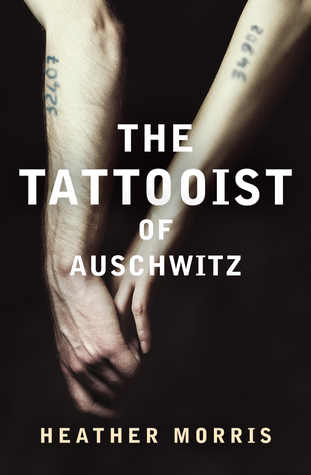

As I understand it: Heather Morris started her career as a screenwriter, and when Holocaust survivor Lale Sokolov approached her with his story, her first instinct was to make a film out of it. But when Lale died before getting into all the nitty gritty, Morris decided, instead, to fictionalise the parts they never talked about; deciding that Lale's incredible tale needed to be told, one way or the other. Unfortunately, great stories don't ipso facto make great novels, and in Morris' novice hands, The Tattoist of Auschwitz just isn't a satisfying book. I remember the narrator in The Storied Life of A. J. Fikry listing off all of the types of novels that he doesn't like, and among them are “literary fiction about the Holocaust...nonfiction only, please”, and beyond any notion of cultural (or, in this case, tragical) appropriation by authors who simply weren't there, I have to agree that only documentary makes for respectful witnessing by nonparticipants. (This short video clip of Lale being interviewed by the author is more powerful than anything in the book's pages.) Nevertheless, I imagine this book will be a big seller and a book club favourite.

All of this is unfortunate because Lale's tale is incredible; the sort of narrative that if it was a movie script, you'd never believe the details. Arriving as a prisoner at Auschwitz in 1942, the young man immediately made a few friends with his optimistic we'll-get-through-whatever-this-is attitude, and when he soon fell deathly ill with Typhus, those friends cared for him. This somehow caught the attention of the camp's tattooist, Pepan – with death all around, sharing resources and risking the ire of the SS was rare; Pepan reckoned that Lale must be a “special one” – and when Lale recovered, he was offered the job of tattoo assistant. Lale didn't really want to take the repugnant role, but he soon saw its benefits: extra rations, days off work when there were no new prisoners transported in, a single room to himself. And with these few freedoms, Lale was able to start a smuggling ring: getting the women who sorted POW's possessions to palm some jewels that Lale then traded to outsiders for food and medicine, which he then shared with as many prisoners as possible. Throughout the story, whenever Lale seems at a moment of greatest danger, someone that he was able to help along the way steps forward to save him; he truly was a “special one” (and while you'd never believe these plot twists in a movie script, any survivor's story in hindsight seems like a strange mix of luck, fate, and coincidence). And yet, this is also a love story: while tattooing a number on one of the thousands of young women who came his way, this former playboy was struck by love at first sight. While in the beginning Lale was determined to survive Auschwitz out of stubbornness and a thirst for vengeance, the eventual need to see Gita safely through the war became his prime motivation:

It is a Sunday when he sees her. He recognizes her at once. They walk toward each other, Lale on his own, she with a group of girls, all with shaven heads, all wearing the same plain clothing. There is nothing to distinguish her except those eyes. Black – no, brown. The darkest brown he's ever seen. For the second time, they peer into each other's souls. Lale's heart skips a beat. The gaze lingers.Most of the story is told from Lale's POV, a few scenes from Gita's, and there is a moment near the end where the two converge; and while the scene itself is straightup Nicholas Sparks – you would not believe this in a movie – I admit I was gasping and teary. That still doesn't make this a great book; the banality of evil is not captured by banal writing:

That night Lale tries to wash the dried blood from his shirt with water from a puddle. He partially succeeds, but then decides that a stain will be an appropriate reminder of the day he met Mengele. A doctor who will cause more pain than he eases, Lale suspects; whose very existence threatens in ways Lale doesn't want to contemplate. Yes, a stain must remain to remind Lale of the new danger that has entered his life. He must always be wary of this man whose soul is colder than his scalpel.The worst thing is that I can totally imagine a tearjerker movie being made of this book, which in my mind removes the story even further from an act of witnessing horror to a purely commercial venture. The story is amazing (there is so much more to explore about Lale's fears of being seen as a Nazi collaborator in his role as Tätowierer; despite his efforts to help as many prisoners as possible), but this book is not up to the material, and the whole project just rubs me the wrong way.