I'm afraid of men because it was men who taught me fear.

I'm afraid of men because it was men who taught me to fear the word girl by turning it into a weapon they used to hurt me. I'm afraid of men because it was men who taught me to hate and eventually destroy my femininity. I'm afraid of men because it was men who taught me to fear the extraordinary parts of myself.

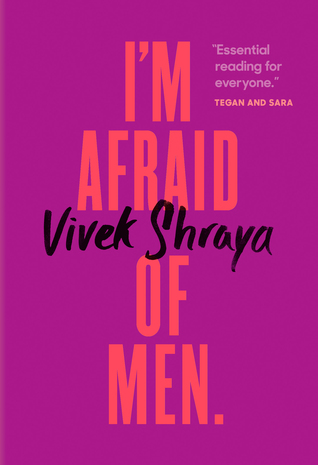

As per her current author blurb, “Vivek Shraya is an artist whose body of work crosses the boundaries of music, poetry, fiction, visual art, and film”, and in I'm Afraid of Men – truly more a long essay than a full-length book – she uses stories from her unusual life to illustrate her journey from being born a boy who was always accused of being too feminine, to coming out as a gay man – who was then accused of not being buff enough to fit into the gay culture – to eventually transitioning into a woman, who is now accused of not being feminine enough. Throughout this process of self-discovery, Shraya has learned to be afraid of men (and women, too) who would confront nonconformity with violence, and while some of her declarative statements weren't quite self-evident to me, I think that hers is an important voice to add to any conversation about gender or sexual nonconformity. Hearing stories about how other people live helps to move them into familiar territory; familiarity must lead to acceptance and safety; here's to a world in which Shraya is no longer afraid of men. (Note: I read an ARC and quotes may not be in their final forms.)

I have to admit that it challenges me to have Shraya describe her time when she presented as a gay man – someone who was butch and buff, spoke in a low register, dressed in neutrals and plaid – and then say that she spent ten of those years in a relationship with a woman. Ultimately describing herself as “a queer trans girl”, Shraya was still presenting as this butch gay man when she met her current boyfriend, and was together with him for a while before she even realised she wanted to transition; it challenges me to think that this boyfriend would stay along for the ride as his male partner became a female (or rather, began to outwardly express that part of herself). Yet, I like being challenged in this thinking; who or how other people decide to love doesn't affect me at all. Even so, some of Shraya's most politically progressive statements made me raise an eyebrow:

• On the heirarchy of harassment, staring is the least violent consequence for my gender nonconformity that I could hope for.But again, I'd rather be challenged in my thinking than read only things that chime with what I already think I believe; and this book gives me plenty to think on. As for what solutions Shraya offers, that was challenging as well:

• In this particular relationship, the process of exposure is especially protracted by how jarring it feels to see my (brown) skin against your pale skin, the skin of the oppressor.

• Whether it's through an emphasis on being large and muscular, or asserting dominance by an extended or intimidating stride on sidewalks, being loud in bars, manspreading on public transit, or enacting harm or violence on others, taking up space is a form of misogyny because so often the space that men try to seize and dominate belongs to women and gender-nonconforming people.

Out of this fear comes a desire not only to reimagine masculinity but to blur gendered boundaries altogether and celebrate gender creativity. It's not enough to let go of the misplaced hope for a good or a better man. It's not enough to honour femininity. Both of these options might offer a momentary respite from the dangers of masculinity, but in the end they only perpetuate a binary and the pressure that bears down when we live at different ends of the spectrum.Just as Shraya now appreciates the “chest hair – a black flame rising from my bra – more than I ever did when I was a boy who regularly waxed and trimmed to adhere to the '90s standard”, she can see a future where “gender creativity” is celebrated and everyone walks down the street, expressing themselves fluidly and without fear of violence. I don't know if I can quite see that future, but I do firmly believe that the first step in any cultural revolution is listening to the stories of others and embracing them as part of the larger human story. I wish for Shraya that fear-free future.