When I was born, the name for what I was did not exist. They called me nymph, assuming I would be like my mother and aunts and cousins. Least of the lesser goddesses, our powers were so modest they could scarcely ensure our eternities. We spoke to fish and nurtured flowers, coaxed drops from the clouds or salt from the waves. That word, nymph, paced out the length and breadth of our futures. In our language, it means not just goddess, but bride.

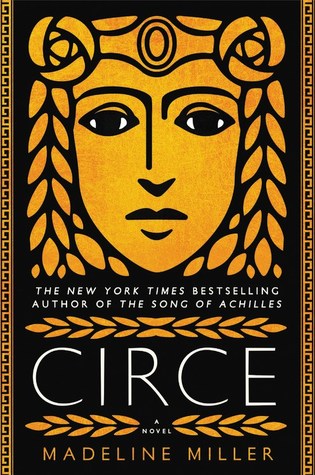

Naturally, I had heard of Circe from Odysseus' story – she was the island-bound witch who had turned some of his men into pigs, forcing Odysseus to employ his famous wit and wiles to save them – but, really, she was no more important to his story than the Cyclops or the Sirens or the Whirlpool; just one more impossible obstacle for Odysseus to overcome on his journey home. What Madeline Miller best accomplishes in Circe is to bring this lesser known figure forward and give her agency: Surely, an immortal deity schooled in pharmakeia and hostile to intruders couldn't be simply charmed into her bed by a silver-tongued human brute? By beginning from Circe's birth and giving her a history, a personality, and plenty of psychological scars, Miller brings a feminist slant to The Odyssey: Circe had her own motivations and desires, and by the time Odysseus showed up, nothing happened on her island without her consent. This is very similar to what Colm Tóibín did for Clytemnestra's story in House of Names (or, for that matter, what he did for the mother of Christ in The Testament of Mary), and what Margaret Atwood did for Penelope in The Penelopiad, and without descending into angry or pedantic smash-the-patriarchy-womyns-lit, these books right an historic wrong and add the female voices and experiences that have long been missing from the human record. And, on every level, Circe's is a great story, well told by Miller.

Brides, nymphs were called, but that is not really how the world saw us. We were an endless feast laid out upon a table, beautiful and renewing. And so very bad at getting away.Because Circe was born the daughter of the sun god, Helios, and his beguiling naiad wife, Perse, she was raised as a goddess. But because she lacked both her father's powers and her mother's beauty, she was mocked and reviled, even by her own family – and it was from this lowly vantage that Circe was able to watch and evaluate both gods and mortals for their weaknesses; a mighty advantage for a budding witch. I've noted before that I don't have deep knowledge of Classical Mythology, and that proved both bane and boon while reading Circe: On the one hand, this powerless and unloved minor deity keeps crossing paths with major figures from the pantheon – Prometheus, the Minotaur, Jason and Medea – and I kept wondering, “Is this canonical? Would Circe have really had a place in all of these well known myths?” But on the other hand, when she met someone like Scylla or Daedalus – some vaguely familiar name that had me thinking, “I should really know who this is, shouldn't I?” – my basic ignorance allowed me to be surprised as the storyline unfolded, and that was totally satisfying. If I had a complaint it would be that Miller uses Circe as a peripheral figure in too many myths, which took some of the energy out of her own plot, but I can't deny that this book also serves as a useful overview of Greek Mythology.

Every moment mortals died, by shipwreck and sword, by wild beasts and wild men, by illness, neglect, and age. It was their fate, Prometheus had told me, the story they all shared. No matter how vivid they were in life, no matter how brilliant, no matter the wonders they made, they came to dust and smoke. Meanwhile every petty and useless god would go on sucking down the bright air until the stars went dark.Circe can't help but be moved by the fate of humans – despite her father teaching her that mortals “are shaped like us, but only as the worm is shaped like the whale”, and her mother sneering that humans look “like savage bags of rotten flesh” – and many times over her deathless life does Circe fall in love with a mortal man; always aware that they will grey and die; always aware that they will ultimately earn a place in the afterlife where they may make amends with those whom they have wronged in life; a final peace denied to her own kind. Circe might feel affection for the struggles of humans, and she might be repulsed by the vanities and cruel whims of her fellow Titans and Olympians, but she is also a goddess who spends generations honing her witchcraft: rapacious seafarers who might think to take rude advantage of Circe's hospitality would do better to refuse her golden cups of wine; this is a nymph who has learned to fight back.

Later, years later, I would hear a song made of our meeting. The boy who sang it was unskilled, missing notes more often than he hit, yet the sweet music of the verses shone through his mangling. I was not surprised by the portrait of myself: the proud witch undone before the hero’s sword, kneeling and begging for mercy. Humbling women seems to me a chief pastime of poets. As if there can be no story unless we crawl and weep.Circe's story starts centuries before Odysseus' birth and continues on long after he has died: as a response to The Odyssey, the Odysseus seen here is just one interesting figure among many in Circe's journey. They may not have had a name for what she was when she was born, but by the end, she could stand on the tallest peak of her island, cloaks billowing, yellow eyes glowing their fraction of the sun, and declare, Be witness now to the power of Circe, daughter of Helios, witch of Aiaia; and god and mortal alike were bound by her charms. That's who Circe was and Madeline Miller makes a honey-toned epic of it.