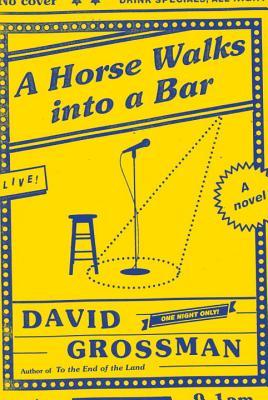

A Horse Walks into a Bar

A horse walks into a bar and asks the barman for a Goldstar on tap. The barman pours him a pint, the horse downs it and asks for a whiskey. He drinks that, asks for a tequila. Drinks it. Gets a vodka shot and another beer...

The usual punchline to “A horse walks into a bar” is “and the barkeep asks, 'Why the long face?'” This Man Booker International Winner for 2017 by David Grossman pretty much takes its entire length to answer, “Why the long face?” Dov Greenstein – or Dovelah G – is an Israeli stand-up comedian, and on the night of his fifty-seventh birthday, he gives his final performance in a basement dive bar. His act is caustic and frantic and A Horse Walks Into a Bar recounts the whole two hours. What at first seemed a hard narrative to enter into (Dov does his best to distance and offend) eventually became an incredibly touching read, with an exploration of modern Israel, family dynamics, and what it takes to transform pain into art. As unserious as a book about an evening of stand-up might seem, this is a deep and thoughtful work, and I don't think that Grossman could have achieved precisely this in any other way.

I gotta be honest with you, I can't stand your city. I get creeped out by this Netanya dump. Every other person on the street looks like he's in the witness protection program, and every other other person has the first person rolled up in a black plastic bag inside the trunk of his car.

The bar is crowded as the evening begins – Dov even seems to have some diehard fans who follow him around – but as the comedian insults and offends individual audience members directly, the crowd dwindles throughout the show. There's a strange tension to this: watching the comedian try to keep the bulk of the audience on his side, even as some people heckle or depart, then throw in some broadly pleasing jokes, and then zing everyone. He gets the crowd singing some anti-Palestinian ditty (that everyone appears to know and that gets them clapping along and belting out the words), and then he confronts them with a mental picture of a young Palestinian mother suffering humiliation at the hands of Israeli soldiers at a checkpoint. An Israeli writer putting these words in the mouth of an Israeli comedian (followed by the generally sour reaction of an Israeli audience) evokes the complex political landscape better than a straight essay ever could. And as a reader, watching Dov sweat and stumble, backtrack and clown, is a really ambivalent experience: I was on his side, but didn't really like him.

He snickers awkwardly, and I remember what he asked me to see in him: the thing that comes out of a person against his will. The thing that only one person in the world might have.

The story is narrated by an audience member: retired district court justice Avishai Lazar. Dov and the judge knew each other briefly when they were boys, and Lazar is present by special invitation; asked to watch and report what he sees. Lazar is dealing with losses that negatively affect his receptiveness at first, but once Dov begins a long story about their common experience at a military summer youth camp, Lazar is rapt. As more and more audience members walk out (“Where are the jokes?”) and Dov begins to tell his story directly to Lazar himself, it becomes clear that the judge will eventually be called upon to render a verdict.

He takes his glasses off and glances at me. I believe he is reminding me of his request: that thing that comes out of a person without his control. That's what he wanted me to tell him. It cannot be put into words, I realize, and that must be the point of it. And he asks with his eyes: but still, do you think everyone knows it? And I nod: Yes. And he persists: And the person himself, does he know what this one and only thing of his is? And I think: Yes. Yes, deep in his heart he knows.

A Horse Walks Into a Bar isn't “ha ha” funny (although it does have some corny jokes that made me go “huh”), but comedians aren't always funny; I can think of some pretty bitter stand-up that has made me uncomfortable; and probably uncomfortable because I could sense that I was getting too close to another person's truths. This was a wonderful way for Grossman to get close to some uncomfortable truths, too, and I'm not surprised that this book has garnered international attention.