She and Ava returned to how they'd been, except Rose was listless and sad. She felt demoted, having to play with her little sister after learning how to identify native plants and build a lean-to with an older girl who was a genius and had the third eye.Little Sister is an odd little book: An examination of consciousness and personhood, it has magical realism, intriguing mystery, and pleasing craftsmanship, but despite really fine writing about grief and guilt and their longterm effects, I didn't connect emotionally to this story at all; I was superficially interested and impressed, but left cold. Somehow, I expect this book will grow on me over time as I can't stop thinking about it; this book has planted roots.

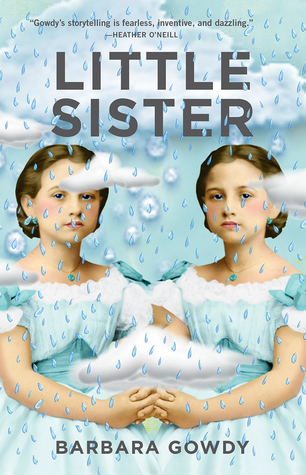

Rose Bowan is the co-owner, with her slipping-into-dementia mother, of a repertory movie theater in Toronto. Thirty-four, overwhelmed with the responsibility of the family business, embroiled in a longterm but casual relationship with the latest in a string of offbeat men, suffering the weight of childhood trauma, Rose has a strange “episode” at the height of thunderstorm season: With the first booming thunderclap, Rose is mentally transported into the body of another woman – Harriet, a sophisticated book editor – and although Rose can feel Harriet's sensations and emotions, she has no control over the other woman's actions. Over within a few minutes, Rose returns to her own body and wonders, “What was that?” and “Why did this Harriet have the same stunning green eyes as my little sister?” When further episodes reveal that Harriet is real (and local!), Rose attempts to track her down, and as Harriet's situation becomes more urgent, Rose starts driving towards storm clouds; hoping to prompt an episode and find a way to influence Harriet's behaviour.

There was a sound like an electrical short, and then deafness, and then, without Harriet, on her own, she was a million miles above Earth, orbiting sooty smudges and silver shafts that found shape and became demons and angels, hideously elastic demons pissing into rusty tin cans, slender stone angels extending glass goblets.The book flips between the today of 2005 and the time of Rose's childhood, starting in 1982. Slips in consciousness are not totally foreign to Rose: as a child, she met an older girl named Shannon – a self-proclaimed genius with the gift of the third eye that made her unbeatable at cards – and together, they attempted a vision quest; an effort to inhabit the bodies of the Oneida who once lived in their Ontario woodlands:

Her voice was lost to the clamour of singing women, a kind of yelling-singing. Rose couldn't understand the words. She stood barefoot on a smooth rock across from a naked baby girl who lay propped up in a crib. The bottom of the crib was wrapped in white fur. Smoky planks of light fell between the trees. Dogs barked. An old man danced in a tight circle and stabbed his spear at the air. The baby gurgled. Her bristly hair seemed to be on fire, but that was an effect of the sun.When tragedy struck her family, Rose went into a state of shock that saw her insisting that the true events of that day were those that she had only dreamed of a few nights before. And this is where everything goes circular: In the present, when Rose describes the first “episode” to her boyfriend, he assumes it is a dream (probably prompted by MSG in her Chinese food dinner). When Rose's research reveals that her episode might be a “silent migraine”, the boyfriend latches onto that – and it's interesting that not only is he a meteorologist (who can warn Rose when thunderstorms are coming), but an employee at the theater is forced to leave early one night with a migraine. Everything feels circular in this book: Rose seems only attracted to polymath geniuses (like the girl, Shannon, that she had known so briefly); both her father and her boyfriend spent their spare time writing manuscripts (that Harriet might consider); Rose's mother is losing her mind in the present while their old neighbour, Gordon, from the past was literally losing his brain as tumours were carved away from it (and from dreams to visions to dementia to brain cancer, these are all presented as altered forms of consciousness that shine a light back on Rose and her episodes). Without giving away any spoilers, I'll note that Rose is self-aware of the coincidence behind why she is so desperate to influence Harriet, and for that matter, much is made of coincidence and “messages from the universe”:

Rose saw the words Temet Nosce. Know thyself, she translated, remembering it from somewhere. It seemed like a message to her personally, like a postscript to the episode: get your own head straight before hanging around in someone else's.I liked the characters and the portrayal of the familiar areas of Toronto; there is a necessary believability to the dialogue and the setting and the people's behaviours that shore up the more fantastical aspects of the plot. But were the more fantastical aspects necessary? That may be the barrier that prevented me from fully connecting to Little Sister, but yet, I can't deny that it was expertly crafted: Barbara Gowdy perfectly achieved the book she set out to write; I guess it just wasn't perfectly the book I sat down to read.