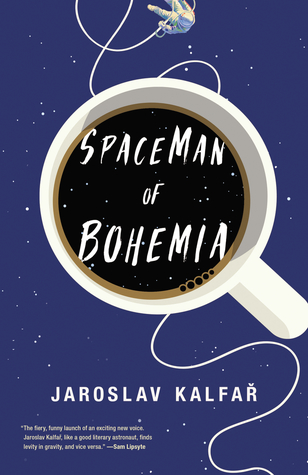

With JanHus1 lie our hopes of new sovereignty and prosperity, for we are now among the explorers of the universe. We look away from our past, in which we were claimed by others, in which our language was nearly eradicated, in which Europe covered its eyes and ears as its very heart was stolen and brutalized. It is not only our science and technology traveling through this vacuum; it is our humanity, in the form of Jakub Procházka, the first spaceman of Bohemia, who will carry the soul of the republic to the stars. Today, we finally and absolutely claim ourselves for our own.Spaceman of Bohemia can be more or less broken into two parts: In the first half, we meet Jakub Procházka – the Czech Republic's first astronaut – as he makes a four month spaceflight towards a storm of cosmic dust that has been captured by Venus' gravity; forming a ring around that planet and purpling the night skies on Earth. Although his preflight psychologist had warned Jakub of the probability of hallucinations (brought on by the stress of a solo voyage), when a giant arachnid alien appears aboard the space shuttle, Jakub keeps its existence a secret from Control and assents to the being probing his mind and memories for an understanding of “humanry”. This device worked really well to share not only Jakub's history, but that of his homeland too – the granting of Czechoslovakia to Hitler in the 30s in an effort to avoid WWII; the West's abandonment of the country to the Soviet Union; the bloodless Velvet Revolution that suddenly saw the local Party elite finding themselves on the wrong side of history: all of this played out within the story of Jakub's own family – and I was totally immersed in the storyline.

And then events happen and the book becomes something else (at the risk of spoiling anything, I do want to note that Jakub's experience from this point echoes that of Jan Hus; the medieval Czech priest/philosopher for whom his spacecraft was named; is that clever or too obvious, especially when spelled out for us?). This second half wasn't bad really, but I was no longer so engrossed.

Wasn’t all life a form of phantom being, given its involuntary origin in the womb? No one could guarantee a happy life, a safe life, a life free of violations, external or eternal. Yet we exited birth canals at unsustainable speeds, eager to live, floating away to Mars at the mercy of Spartan technology or living simpler lives on Earth at the mercy of chance. We lived regardless of who observed us, who recorded us, who cared where we went.I didn't flip to the author bio until I reached this second half, and when I saw that Jaroslav Kalfař has a hipster beard and an MFA and is living and writing in Brooklyn, that suddenly made sense (and I'll say here again that I'm not generally a fan of hipster-bearded, Brooklyn-based writers with MFAs; Spaceman employs the same brand of energy-draining satire I dislike from, say, Gary Shteyngart). On the other hand, it was interesting to read that Kalfař was born and raised in Prague, relocating to the US at fifteen. So, putting aside all the efforts at philosophy and the exploration of humanry that didn't really resonate with me, I thought that Spaceman did a wonderful job of exploring the Czech experience: rural peasant life and urban yuppidom; years of living under totalitarian control and now striving for Capitalist decadence; the pride of a people who honour the great personages in their past and yearn to see the birth of a modern legend; all that I learned about the Czech people was worth the entire (less than fulfilling) reading experience.