I go in the back door to the kitchen. Open a cupboard, click. Take out a tin of tuna chunks and close the cupboard, thunk. Pull the ring on the can, click, again; a smaller, sharper click. Open the cutlery drawer, jangle, and select a fork, clink. Pick an ant off my sleeve and flick it down the sink. I breathe. I breathe. I breathe.

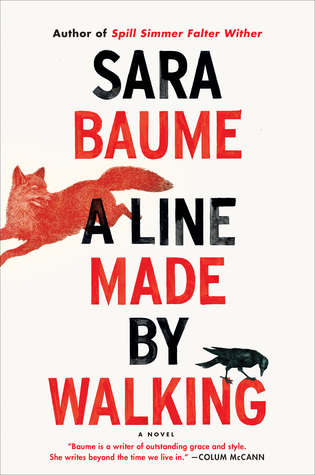

And all of this time, I am trembling.A Line Made by Walking is apparently semi-autobiographical – like the main character, Frankie, author Sara Baume attended art school in Dublin, worked in a gallery there, and had some kind of existential/emotional breakdown – and that knowledge nudges me to tread carefully: Who am I to say that this book doesn't precisely capture the essence of a very real human experience? Here's my overthought takeaway: I really loved Baume's writing about Frankie's inner struggles and the details of how she dealt with them, and I was interested in Frankie's ideas about art and how she uses it to understand her own life, but there are formulaic devices in this book that strained my patience and drained away much of my empathy. After Spill, Simmer, Falter, Wither, I wanted to love everything Baume; and I didn't love this.

When we meet Frankie, she's a twenty-five-year-old gallery worker who, after completing art school years before, lost her passion for creating art. She has some friends – or, at least, co-workers – a set routine, and a bed-sit apartment in Dublin. And then one night she realises it isn't enough – she collapses to the floor and sheds unending tears into her grimy carpet – and when she finally gathers the strength, she asks her mother to come and get her and bring her back to their village home. Because Frankie's grandmother had died a couple years earlier – and Granny's country bungalow wasn't attracting any buyers – Frankie is able to convince her parents to let her live there for a while as she figures out her life.

It wasn't my parents who annoyed me; it was the forsaken version of myself I helplessly revert to in their presence; it was the fact that my life was suddenly wide open. I had not yet, at that point, decided whether I wanted to get better or die altogether.Frankie makes several references to “waiting to die” and not caring if she does or not, and while her mother recognises her daughter's fragility and insists she visit the family doctor before moving out to the country alone, Frankie is unimpressed that two different, harried doctors immediately wrote her a prescription; both of which Frankie refused to fill. Again, I understand that this mirrors Baume's own experience, and while I can't deny that there is an overmedicalisation in the mental health field, I don't know what to think about this: Neither doctor spends enough time with Frankie to properly diagnose her, but the reader can see that she's in trouble; yet, as a reader with no experience of mental illness, I have no idea if Frankie should be medicated (and I'll note that Frankie doesn't just seem to suffer from depression, but she describes a lifetime of OCD and serious paranoia, as well). Is this just some “quarter-life crisis” that everyone needs to wait out, as Baume apparently did? Could “wait it out” be a dangerous message for those who would benefit from medication? No clue, and I wish Frankie's mental state had been made clearer.

Because my small world is coming apart in increments, it seems fitting that the creatures should be dying too. They are being killed with me; they are being killed for me.As to the art: Not long before Frankie's breakdown, she decides to photograph a series of found, dead animals; starting with a robin in her city garden. Each chapter is named for a type of animal (Robin, Rabbit, Rat...), and it immediately becomes clear that Frankie will eventually find a dead robin, rabbit, rat, etc. in each so-titled chapter. That was one of the devices that began to wear on me (there's nothing shocking [or artful?] or otherwise emotional about happening upon the dead frog one has been expecting), but the more wearying device was Frankie's mental “testing” of herself: She would see an object or think of a concept and then conjure from an apparently eidetic memory an art piece centered on that object/concept:

Why must I test myself? Because no one else will, not any more. Now that I am no longer a student of any kind, I must take responsibility for the furniture inside my head. I must slide new drawers into chests and attach new rollers to armchairs. I must maintain the old highboys and sideboards and whatnots. Polish, patch, dust, buff. And, from scratch, I must build new frames and appendages; I must fill the drawers and roll along.There's something ironic about this particular metaphor – taking responsibility for the furniture in her head – when Frankie can't muster the energy to take care of the furniture in her grandmother's house; no urge to sweep up the dead flies by the sitting room window; no desire to remove the desiccated slug from the bathroom mirror. To demonstrate this “testing” device, this is the book's titular example:

Works about Lower, Slower Views, I test myself: Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking, 1967. A short, straight track worn by footsteps back and forth through an expanse of grass. Long doesn't like to interfere with the landscapes through which he walks, but sometimes he builds sculptures from materials supplied by chance. Then he leaves them behind to fall apart. He specialises in barely-there art. Pieces which take up as little space in the world as possible. And which do as little damage.

I do like this example – as the artwork captures and makes visual something of Frankie's barely-there existence – but this device is used over seventy times in ten chapters, and that's too much for me; they eventually felt like filler and I grew to dread coming upon another. And it probably exposes me as a Philistine, but I couldn't engage with most of the conceptual artpieces that Frankie describes, even though she explains what's important about them (and as Baume explains in an afterword, these are only meant to be Frankie's interpretations; we are encouraged to discover ad interpret the art as we like). I was already one of the great unwashed who doesn't “get” My Bed by Tracey Emin (People were so angry over that bed; they did not realise it was the easiest piece of art in the world with which to identify), so there's not much chance that I'd see the genius in someone punching a clock-card at the strike of every hour for a year (Hsieh's One Year Performance) or the blinking lights of Creed's Work No. 227: The lights going on and off; as Baume says of the latter:

I love what it might mean. The light and dark in everything, the reaction to every action, the prodigious unpredictability of life. And I love the possibility – the audacity – that it might mean nothing at all.And a last observation: We eventually learn the extent of Frankie's paranoia about strangers, and where it may have come from. When I read the bit about Frankie and her sister having discussed the bad guys' method of rolling an empty pram onto the road to get a car to stop, I thought there was probably something very significant about them having decided as a credo: Remember the golden rule? Always hit the baby. I thought that this – hit the baby/photograph the roadkill – was likely the nexus around which the whole narrative revolved, but there's always the possibility – the audacity – that it might mean nothing at all.

There's not a whole lot of plot to A Line Made by Walking, so it really comes down to what's going on in Frankie's head. Where she was dealing with what was real (her experiences, emotions, fears), I was totally engaged. But all the parts that read as little more than a catalogue of Tate Museum exhibitions felt formulaic and left me cold; not least of all because I don't feel engaged by the type of high concept art that she's describing (my own failing, I know). I understand that Baume has become motivated to take up her visual art again, and I'd be interested to see what she creates. And if I need to wait years and years before she writes another book, I'll be interested to see what she creates on the page at that time, too.

I really did like that Frankie suffers the same brand of solipsism that I did at her age -- when the universe appears to be talking to you, who wouldn't listen? -- and she is forever surprised to think of someone just before they call; or try to remember something about penguins right before catching a radio programme about them. I found it amusing to have found a Planet of the Apes reference in the last book I read (Lorrie Moore's use of "a planet of the apings!" to describe learning to date again after divorce) because that is Dave's biggest pop reference, and then I found it doubly amusing to find a Land Before Time reference in this book -- and especially as my own soon-to-graduate-with-an-art-history-minor daughter is both a Land Before Time fan/collector and someone who is exasperated by her mother's inability to see the genius in modern conceptual art pieces; she rather likes My Bed. So for Kennedy I include:

Back in the kitchen, I see there's a leaf stuck to my sneaker. Small, yellow, sycamore, like the one which obsessed Littlefoot in The Land Before Time. The leaf of the last growing tree which kept the herbivorous dinosaurs alive. Perfectly centered on my toe, as if it was the only visible part of an invisible pattern.Ah, who isn't solipsistic in the face of "invisible patterns"? Although I have never before encountered Littlefoot in a work of literature, Kennedy says this will become significant only if there's an Army of Darkness reference in my next book; her sister's number one pop reference.