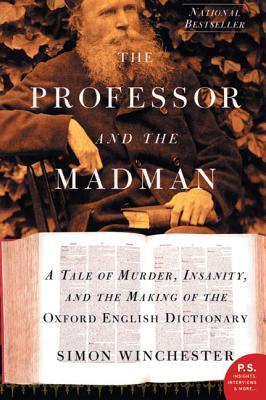

Sir Joshua's words were to provide the starting point for a relationship between Doctor Murray and Doctor Minor that would combine sublime scholarship, fierce tragedy, Victorian reserve, deep gratitude, mutual respect, and a slowly growing amity that could even, in the loosest sense, be termed friendship.This is how The Professor and the Madman was described to me: When, in Victorian England, the Oxford English Dictionary was first being compiled, its editors put out a call for volunteer readers; people who could peruse books both old and new, looking for quotes which perfectly define specific words embedded within them, most especially looking for the dates when words first appeared in English, or the turning points at which their meanings changed (I now realise that I've never had the pleasure of flipping through a copy of the OED, but these quotes and dates are apparently its claim to fame). Professor James Murray was the editor of the project, and after receiving tens of thousands of excellent submissions by a Dr. W. C. Minor, Murray was shocked to discover that Minor was being held in a lunatic asylum outside London. I was promised that this is a fascinating story of both the creation of the OED itself and the friendship between these two men. While the book does more or less sketch out these two potentially interesting narratives, I don't think that author Simon Winchester really pulled it off: he seemed to focus on the wrong things – never going into anything too deeply – and with a florid and nonacademic writing style, I never caught his enthusiasm for the tale.

It is a book that inspires real and lasting affection: It is an awe-inspiring work, the most important reference book ever made, and, given the unending importance of the English language, probably the most important that is ever likely to be.The Professor and the Madman was released in 1998 – a year in which I and everyone I knew already had the internet – so right from the start, I can't believe that Winchester seriously thought of the OED as the “most important reference book ever made” or “that is ever likely to be” (I won't even touch his assertion that English was and is the most important language in the world). While in Victorian times the idea of crowdsourcing the quotes must have seemed revolutionary, imagine how much easier it would be to start from scratch on a project like this today (think Wikipedia or Reddit), and with the Gutenberg Project and other public sharing of old books, I assume that the OED is constantly being amended with better quotes at an exponential rate. All this to say: Yes, you can still order the multivolume set of the OED for a thousand bucks, but in today's world, it kind of fails as a book; there's no point in printing out something so inherently improvable; I categorically reject Winchester's primary thesis. On the OED itself and other details, Winchester's personal opinions made my eyes roll hard:

Murray's interest in philology might have remained that of an enthusiastic amateur had it not been for his friendship with two men. One was Trinity College, Cambridge, mathematician named Alexander Ellis, and the other a notoriously pigheaded, colossally rude phonetician named Henry Sweet – the figure on whom Bernard Shaw would later base his character Professor Henry Higgins in Pygmalion, which was transmuted later into the eternally popular My Fair Lady (in which Higgins was played, in the film, by the similarly rude and pigheaded actor Rex Harrison).Professor Murray's story was quickly told and interesting enough from what we learn (he was an autodidact polymath who became a school teacher, and by pursuing his interests in philology and etymology, he befriended and was hired on by those who would embark on the OED project), and although Dr Minor's story is more detailed (and more dramatic), Winchester repeatedly resorts to conjecturing, Is that what drove him mad? Is this? To summarise: Minor was raised in Ceylon by Missionary parents, went to Yale, became a medical doctor, and enlisted for the Union Army during the American Civil War. He witnessed horrorshows on the battlefield, was forced to brand the cheek of an Irish mercenary with a D for desertion, and soon became unfit for service. When he was released from the army, he spent all of his time and money on prostitutes, and as he became more and more paranoid that “the Irish” were out to get him, Minor decided to relocate to London. In a paranoid fit one night, he ran into the street and shot the first man he saw: George Merrett, an impoverished workingclass husband and father of six children. Found not mentally responsible, Minor was held “at Her Majesty's Pleasure” at the Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum, where he was given a suite of rooms, permission to acquire an enviable library, and it was from here, with his limitless leisure hours, that Dr. Minor was about to find and write out his many thousands of submissions. While his contributions to the OED were perfectly suitable, he remained disturbed: believing that people broke into his room every night and performed unspeakable acts to his body. Over and over, Winchester makes conjectures: wondering if it was exposure to naked swimming girls in the Ceylon of his youth that caused Minor to have a lifelong fixation on the sexualising of little girls (and he mentions this about little girls near the end without having been specific before about Minor's sexual “momomania”); Winchester wonders if it was PTSD from the war or specifically a fear of an Irish vendetta that fueled Minor's paranoia; and in what I thought was a tasteless bit of conjecture, after noting that Minor performed an autopeotomy (look it up), Winchester writes:

No suggestion exists that the meetings between Minor and Eliza Merrett were anything other than proper, formal, and chaste – and perhaps they always were so, and any residual guilt that Minor may have felt stemmed from the kind of fantasies to which his medical records show him to have been prey. But it has to be admitted that it remains a possibility – not a probability, to be sure – that it was guilt for a specific act, rather than some slow-burning religious fervor, that prompted this horrible tragedy.So, the murder victim's widow – whom Minor had the means to assist financially throughout the years – would sometimes visit him at Broadmoor, and although Winchester could find no evidence that anything improper happened between them, he just thought he'd throw it out as a possibility. That's just wrong.

And here was what I thought to be the biggest fail in the book: In the Preface to The Professor and the Madman, Winchester writes of the first meeting between Murray and Minor, saying that the Professor, after corresponding with one of the OED's most prolific contributors for over twenty years, finally decided to board a train and make his way to Dr. Minor's address. Pleased to have his train met by a stylish carriage, Murray is even more impressed when the coachman turns into an oak-lined lane and arrives at an enormous mansion. Murray is shown inside, and when he is presented to a finely dressed gentleman in a book-filled study, Murray extends his hand and says, “Dr. Minor, I presume.” “Oh no,” says the other, “I am the warden of this lunatic asylum and Dr. Minor is one of my sickest patients.” That's a great story: too bad it never happened. After opening with this anecdote, I spent the next two hundred pages believing that this was the way it happened and was dismayed to read near the end that this was merely the tabloid invention of an American journalist; Murray was aware of Minor's situation from the start (yes, to be fair, Winchester begins with, “Popular myth has it”, but I read that as, "This story has reached the level of myth", not, “I'm starting this nonfiction book with something you shouldn't believe”, and I felt tricked; even the Goodreads book synopsis details this version of the story).

This could have been a totally fascinating book – I'm sure there were more stories about the literally tons of submissions that were sent to the Scriptorium by eager contributors; I would have liked much more information about that whole process (it took seventy years from conception to completion!) – and so much more could have been written about Murray and Minor, Victorian mental health care, and the murder victim and his family. This could have been a great book in the right hands, but I just don't think Winchester was up to the job.