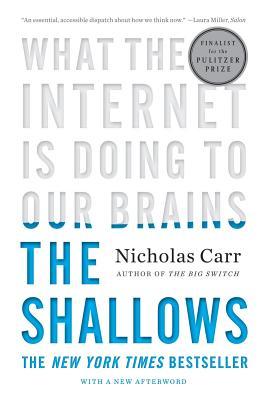

The Net's interactivity gives us powerful new tools for finding information, expressing ourselves, and conversing with others. It also turns us into lab rats constantly pressing levers to get tiny pellets of social or intellectual nourishment.The Shallows was recommended to me as “important and fascinating” by a retired schoolteacher, and based on her age and life experience, I can totally see what she got from this book. It is an interesting mix of neurobiology, the history of human technological achievement (and how these milestones rewire the way our brains work), and a scary-sounding warning about how we embrace new technologies at the risk of our own humanity. So far as the research into science and history goes, this was indeed “important and fascinating”, I'm just not sure if I agree with Nicholas Carr's Doomsday conclusions; and as the latest research included is from 2009 (a lifetime ago in terms of the Internet Age; iPads were new and MySpace was still a thing), it may not be totally relevant anymore.

The basic gist: When we read a physical book, synapses fire in our brains, creating new and lasting neural connections, and it is the specific nature of slow, focussed, and solitary reading that causes this to happen. By contrast, the reading we do on the Internet (filled as it is with hyperlinks, ads, and other distractions) happens too quickly to be sent to long-term memory; there are no new connections made in the brain, and therefore, no real learning; no wisdom will be gained. Carr even says that reading a book on a Kindle-type device is too distracting to equate to real reading, and although I don't have such a device, is that really true? He makes the point that being able to highlight unfamiliar words for instant definition is too interruptive for focussed reading, but is that really more disruptive than putting the book down and reaching for a paper and ink dictionary? Carr also chastises those who mistakenly claim that we are freeing up room for creative thought by storing everything we used to learn by rote onto the Internet:

We don't constrain our mental powers when we store new long-term memories. We strengthen them. With each new expansion of our memory comes an enlargement of our intelligence. The Web provides a convenient and compelling supplement to personal memory, but when we start using the Web as a substitute for personal memory, bypassing the inner processes of consolidation, we risk emptying our minds of their riches.So, Carr's conclusion is that turning, en masse as a society, from book reading to Internet reading is causing us to rewire our brains in a way that's different from what we've become accustomed to. What seems to be lost in this argument is that reading books themselves has rewired our brains in every new generation since Gutenberg, and I can't see the point in looking at one system of rewiring as “good” or the other as “bad”; technological leaps are inevitable and beyond such moralising. Either way, short of some apocalyptic event that knocks us out of the electronic age, this genie is out of the bottle and I wouldn't be using the Internet every day if I didn't find value in it. Interesting read.

I was coincidentally reading this book review yesterday for Magic and Loss (about seeing the Internet as art) and I'm noting this here so that I will remember to read it one day as a counterbalance to Carr's doomsaying.