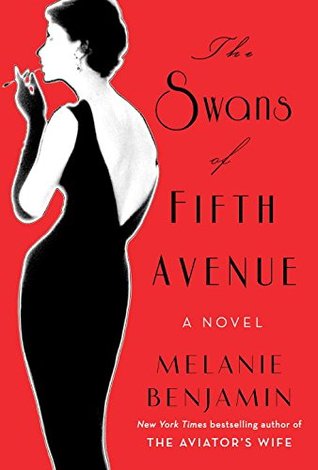

Beauty. Beauty in all its glory, in all its iterations; the exquisite moment of perfect understanding between two lonely, damaged souls, sitting silently by a pool, or in the twilight, or lying in bed, vulnerable and naked in every way that mattered. The haunting glance of a woman who knew she was beautiful because of how she saw herself reflected in her friend's eyes.I picked up The Swans of Fifth Avenue because it was on some list or other of the most anticipated books of the year, and knowing that author Melanie Benjamin had a big success with The Aviator's Wife (which I haven't read), I thought I may as well be in on what other people are looking forward to reading in 2016. If I had known that it was about those fabulous fashion icons of the Fifties and Sixties – the Ladies who Lunch (without ever actually eating; Givenchy and Balenciaga require a certain emaciated drape dontchaknow) – then I may well have given this book a pass: I've never seen an episode of Real Housewives of Wherever and don't much care about the inside story of trophy wives. But The Swans of Fifth Avenue does have a little something else going for it that elevates the story just a smidgen: Truman Capote, and his entire literary trajectory.

Swans is primarily about the friendship between Capote and the undeniable leader of the Manhattan social scene of the Fifties and Sixties, Babe Paley (wife of the megawealthy Bill Paley, founder of CBS). From the moment they met, Capote and Babe knew that they had a special kind of friendship:

At this point, Capote was an exuberant and attractive young man who was able to charm women and disarm men with his campy gay manners and bitchy gossipmongering – anyone who was anyone wanted Capote at their dinners and parties, trusting him to perform as an amusing lapdog. Babe, on the other hand, saw through the camp and believed the two of them to have a meaningful friendship; probably the only real love she felt in her life. (And at this point we're supposed to feel sorry for Babe, whose controlling mother raised three daughters who all made important marriages, and although Babe was adored in print and magazines as the trendsetter of society, and although she had all the money and servants and jet-setting vacations that anyone could want, she was also married to a man who slept around; a man whom Babe never let see her without flawless makeup over decades of marriage. Poor little rich girl.) And yet, Babe grew ever closer to Truman:A beautiful – an exquisite – woman. Needing him, as he needed her. For what, neither could precisely express just yet. They only recognized each other, not as reflections in a mirror, but as a reflection of a deeper, darker, murkier sore, or hole, or something gaping but always, always hidden. Until the moment they locked eyes on the CBS plane, each so startled their masks fell, and Truman was, for only a fragment of a moment, no longer the startlingly self-assured prodigy but a lost little boy, forgotten. And Babe was, beneath the couture and makeup, a shy, unsure woodland creature, hugging herself for comfort. Two souls, exposed like raw wounds. Visible only to each other, they firmly believed.

She wanted to be his mother, and his lover, both in one day, and the different emotions, jaggedly different, biblically different, made her disoriented, dizzy once more.As the beautiful people have their lunches and swap complaints about their husbands, Capote is always at the fringes, listening and recording. We watch as he releases Breakfast at Tiffany's (which he swears isn't based on any one of his friends in particular), and it's with real pride that the ladies watch Capote become a literary superstar with In Cold Blood. And while I certainly had heard of Capote's Black and White Ball of 1966, I hadn't realised that its purpose was to announce Capote's arrival at the level of wealth and prestige of his friends; Capote wasn't willing to be anyone's lapdog anymore.

In 1975, Capote published an excerpt of his latest manuscript in Esquire; a piece entitled La Côte Basque, 1965. In it, thinly disguised caricatures of all his dearest lady friends – Babe Paley, Gloria Guinness, Pamela Churchill, and Slim Keith – expose all of their dirty laundry (ahem), and he uses this piece to settle scores with old enemies like Ann Woodward. The ladies can't believe Capote betrayed them like that, Capote refuses to believe that anyone would ever tell a writer anything that they wouldn't expect to see in print some day, and the public generally agrees that it was at this moment that Capote had committed social suicide. It might also be when Capote's muse deserted him: this final manuscript was never finished and Capote lived out his days becoming an ever-more cartoonish version of the bitchy gay socialite.

So, I ended the book still not caring very much about the fabulous people (each of these ladies traded her youthful beauty for riches and leisure, and as we all understand in real life, Faustian bargains imperil the soul), but as a framework for Truman Capote's literary career, there is a really interesting story here. As for the writing, I found it annoyingly overblown. These passages I've selected are totally representative of the whole, so if you think they're lovely, you'll probably enjoy the whole book. I didn't much.