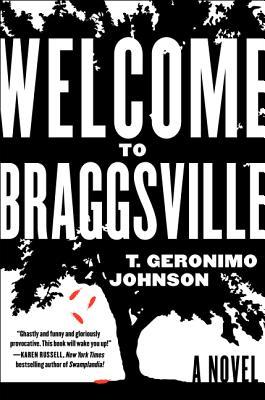

The deputy stared closely, searching, like he was looking to see if Daron was going to lie, the look the cops would give him when they pulled him over on weekends in high school, the looks teachers sometimes gave him as they handed back his papers. It asked, Are you really one of us?T. Geronimo Johnson could not possibly be more au courant with Welcome to Braggsville. With today's headlines crowded with the on-campus wars against “microaggressions”, the sudden and urgent need for “safe spaces”, Yale students who don't accept that Halloween costumes constitute free speech (or even allow a professor to exercise his right to free speech in defense of his wife's stance on the matter), and on the other hand, those in the American South who declare that the continued flying of the Confederate Flag is a question of heritage – certainly not racism – and who respond to #BlackLivesMatter with #AllLivesMatter, and those who believe that the real threat to American society is the invading Mexicans: all of these issues are confronted in this outstanding book. Sometimes funny and satirical, sometimes a fist in the gut, Johnson has written a complex work that is equally challenging and mind-expanding; to be certain, no cows are sacred; no prisoners taken.

D’aron Little May Davenport (of a hundred nicknames, loving or cruel) grew up in the town of Braggsville, Georgia, population 712. Valedictorian, vegetarian, victimised because of the first two labels, D'aron applied to Berkeley behind his parents' backs, hoping to get as far away from his backwater upbringing as possible. Although lonely and underachieving at first, D'aron follows his academic advisor's advice to find a tribe, and at a campus party meets “a Malaysian who looked Chinese to some and Indian to others, fancied himself black at times, and wanted to be the next Lenny Bruce Lee; a preppy black football player who sounded like the president and read Plato in Latin; and a white woman who occasionally claimed to be Native American”. Immediately, this odd assortment became inseparable – referring to themselves, ironically, as The Four Little Indians – and in their company, D'aron felt equal and accepted for the first time in his young life.

During a second year course that the four were taking – “American History, X, Y, and Z: Alternative Perspectives” – D'aron let slip that his hometown held an annual Civil War reenactment as part of their Pride Week Patriot Days Festival, and the class went berserk with indignation: “Are barbers still surgeons? Is there still sharecropping? What about indoor plumbing?” At their professor's urging, The Four Little Indians plan a trip to Braggsville, intending a performance art project that was supposed to shine a light on the subtextual racism of the event, but everything goes horribly wrong.

And I mean horribly. I had to put the book down here and walk away for a bit. When I came back to it, mentally shifted, the book had also shifted into an aftermath story: complete with 24 hour newschannels, an FBI investigation, and a Rainbow Coalition elbowing for room amongst the KKK and the Nubian Black Separatists at the end of the drive. Trying to explain their intended purpose to the Sheriff, one (in addition to eschewing quotation marks, Johnson doesn't identify who's speaking and it can often be hard to tell by context, especially in this interview sequence where individual answers are run together) explains:

It's a form of 4-D art. It's activism. It's the way of the future. No one writes letters anymore. Mass marches are inherently exclusive because access is restricted by geography and mobility, thereby fortifying the enduring social asymmetry they seek to undo. Instead, imagine a thousand performative interventions wherever injustice occurs, whenever it occurs. Social justice meets vaudeville. Or the troubadour. It's the poetry of performance. Me, you, black, white. It's all an act, Sir. Vershawn Ashanti Young says even race is a performance, Sir.It's not until this incident that D'aron even recognises the institutionalised racism of his hometown: sure, everyone has black lawn jockeys flanking their driveways, and, sure, no black folks actually live in Braggsville proper (they have their own community called the Gully on the other side of the Holler – isn't that the way theyselves want it?). D'aron also needs to confront the racism that he has buried within his own self when his first reaction to a suspected rape is to grab a gun and head for the Gully. Eventually, D'aron learns that his neighbours are more organised than he ever suspected: just don't call their paramilitary group a militia; it's simply a collective:

We're not a threat, a fringe group, or crazy. We're the legacy the forefathers fought to build. We're not antigovernment, we're procitizenship. We're not antigovernment, we're anticorruption. We're not antigovernment, we're pro-self-sufficiency. We're not separatists or racists, we're constitutionalists. We judge a man by his actions, not his skin color. The Bill of Rights tells us that all men are created equal. We know our history and revere it. We are citizens. We are your neighbors. We represent all the county – all the surrounding town. We are your anchor in this rough sea.Without going into the specifics of the plot, that's what Welcome to Braggsville is all about; this confrontation between the two self-important, gobbledygook-speaking worlds that D'aron straddles. It's a book about belonging and what makes a family or a community or a country. It's a book about how people self-segregate into like-minded groups; which only reinforces self-righteousness and the fear of others. As I started with, these are timely and important concepts, ripe for literary dissection. So, does Johnson pull it all off?

According to the author bio, Johnson has an MFA from the Iowa Writer's Workshop and an MA in language, literacy, and culture from UC Berkeley – does that ring warning bells, perhaps? Mightn't that caution a reader that she is about to read a book that has been Written with a Capital W? I was consistently charmed by the storytelling in Welcome to Braggsville, but every now and then, there would be some authorial trickery that would feel a bit too clever (like changing the spelling of D'aron to Daron and back and forth to, I suppose, denote which world he is currently identifying with). As an extreme example: after referring obliquely a few times to The Four Little Indians eating barbecue with RVers at Six Flags, there is eventually an academic paper included, in full, dissecting the experience as though it was a planned sociological experiment instead of an anecdote from real life. In the appendix at the end of the book that holds the footnotes for this “paper”, there are numerous legitimate sources, including several references to T. Geronimo Johnson's own works; including several references cited from Welcome to Braggsville itself. Brilliant or mere wankery? A reader's tolerance for this type of thing would likely determine that reader's overall experience.

I do enjoy novels that push the limits of the form and I love reading authors who obviously enjoy playing with language, but for me, too much wankery will cost a star. Welcome to Braggsville confronts important truths without assigning blame and it does a good job of deflating the self-important who walk amongst us; I am not at all surprised to see this title on the longlist of the 2015 National Book Awards. A worthwhile and challenging read.

As I spend time going on campus tours with Mallory, I am constantly aware of the politics of the various schools we're visiting, hoping she doesn't end up choosing a radical school. Hence, my dilemma.

She tells me that Laurier has the best program for her, and the only mark she currently has against it, is that it's too close to home (and as someone who was expected to go to university in town, I understand Mallory's desire to have the full meal deal experience). I would love for her to stay at home for school (even with her "maybe first year in residence" proposal), but Laurier is recently in the news.

In a nutshell, the school was recently chosen as the site of an assemblage of statues of all of the Canadian Prime Ministers -- something that doesn't currently exist anywhere in the country -- hopefully to be completed before Canada's 150th birthday in 2017. Just as ground was broken, the protests began. From a professor:

It’s disingenuous to make a commitment to indigeneity and recognize that land belonged to First Nations people and then go and erect statues of leaders who took the land away from them, and were responsible for policies of genocide.And from a fourth year student (who identifies as Metis):

It will create, at the very least, an uncomfortable environment for 99 per cent of students to walk through a place filled with statues of white men and one white woman, people who have perpetuated crimes against First Nations.And so that is where we are in this country: officially told to be ashamed of our history, and not just ashamed of those first leaders who did, indeed, approve of atrocities, but ashamed of all of our Prime Ministers and the project has been halted. Imagine an England that couldn't erect a statue of Nelson or an America without the memorials to Jefferson and Lincoln. I don't know if I want my daughter to go to a school that has an official policy of despising our heritage instead of taking the opportunity to examine and contextualise it. And does no one else see the irony of protesting erecting these statues on the grounds of a school that was named after Canada's seventh Prime Minister? Doesn't that mean that "99 per cent of students" currently need a trigger warning to even enter the buildings every day?If nothing else, Welcome to Braggsville shines a light on such academic wankery.