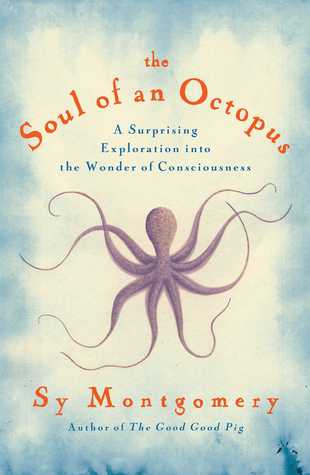

In 2011, nature writer Sy Montgomery's article on getting to know a captive octopus named Athena in Orion magazine was so popular that she was given the opportunity for further research in order to expand the article to book length. Montgomery became a regular fixture at the New England Aquarium – where she bonded with several more octopuses, among other species – and was even brought along on octopus-research dives in Cozumel and Southeast Asia. While I have no doubt that these additional learning opportunities were fascinating for Montgomery, I don't know that Soul of an Octopus adds appreciably to the original article.

I'll admit I'm one of those people who find octopuses (and yes, that's the right word – apparently “octopi” is wrong because you can never add the Latin “i” to pluralise a Greek-rooted word) totally alien and creepy – the bonelessness and suckers and beak have always weirded me out. But it didn't take very long – essentially the first chapter of this book, which is a rewriting of the original article – for Montgomery to get me to look at octopuses in a new light. As one of the aquarium's staff tells her, “Just about every animal can learn, recognize individuals, and respond to empathy.” Montgomery shares research and anecdotes that prove that a huge range of animals have distinctive personalities – from lobsters to fruit flies – and with the addition of her own interactions with octopuses, it becomes apparent that these strange cephalopods are as friendly, curious, and intelligent as puppies. I love learning something like that.

My problem with this book, however, is the lengths to which Montgomery stretches in order to make a book out of her article. She has many long passages with vaguely related tidbits of info, as in:

While stroking an octopus, it is easy to fall into reverie. To share such a moment of deep tranquility with another being, especially one as different from us as the octopus, is a humbling privilege. It's a shared sweetness, a gentle miracle, an uplink to universal consciousness – the notion, first advanced by pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Anaxagoras in 480 BC, of sharing an intelligence that animates and organizes all life. The idea of universal consciousness suffuses both Western and Eastern thought and philosophy, from the “collective unconscious” of psychologist Carl Jung, to unified field theory, to the investigations of the Noetic Sciences founded by Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell in 1974. Though some of the Methodist ministers of my youth might be appalled, I feel blessed by the thought of sharing with an octopus what one website (loveandabove.com) calls “an infinite, eternal ocean of intelligent energy.” Who would know more about the infinite, eternal ocean than a octopus? And what could be more deeply calming than being cradled in its arms, surrounded by the water by which life itself arose? As Wilson and I pet Kali's soft head on this summer afternoon, I think of Paul the Apostle's letter to the Philippians about the power of the “peace that passeth understanding...”And if the hippy-dippy philosophy of that quote seems out of place in a science book, it's actually a recurring theme, with Montgomery later musing about cultures that use stimulants to expand their minds:

In my scuba-induced altered state, I'm not in the grip of a drug: I am lucid in my immersion, voluntarily becoming part of what feels like the ocean's own dream.Soul of an Octopus is fluffed out by such diverse and extraneous information as the incompetence of the customs officials at Logan Airport, documenting the earaches that Montgomery suffered while scuba diving, or most incredibly, by sharing the intimate details of a teenage suicide (that of a friend of a friend, no less). In what seems like a short time, Montgomery meets, bonds with, and experiences the death of three different octopuses at the aquarium, and after she had convinced me to better appreciate their lives, I was appalled when Kali's death came down to human error: Weighing 21 pounds and with an arm span of nearly ten feet, she had squeezed out of a hole that measured two and a half inches by one inch. (By the way, that kind of boneless shape-shifting is what I find most creepy about octopuses.) But I was really put off by Montgomery's conclusion about Kali's ill-fated escape attempt:

Like the astronauts who died blasting off in the Challenger, or the brave men who perished in attempts to find the source of the Nile, penetrate the Amazon, visit the poles, Kali had chosen to face unknown dangers in the quest to widen the horizons of her world.Or, you know, she was just trying to escape at her first opportunity after months in a pickle barrel. Having learned about the very short lifespan of octopuses, and the constant dangers they face in the wild, I'm not particularly outraged (as others seem to be) by a well-funded and thoughtful institute like the New England Aquarium keeping them on display; public education can only lead to more understanding; more desire to protect the oceans and their mysteries. And now, dangit, I'm having calamari-remorse.

In the end, everything you need to know is in the original article, but if it totally fascinates you, this book isn't a total waste of time.