The Good Lord Bird don't run in a flock. He flies alone. You know why? He's searching. Looking for the right tree. And when he sees that tree, that dead tree that's taking all the nutrition and good things from the forest floor. He goes out and he gnaws at it, and he gnaws at it till the thing gets tired and it falls down. And the dirt from it raises other trees. It gives them good things to eat. It makes 'em strong. Gives 'em life. And the circle goes 'round.I suppose it makes sense that in a world where some substantial percentage of young people get their news solely from Jon Stewart and The Daily Show, authors might try to connect to readers by presenting historical facts through a satirical or farcical lens. In The Good Lord Bird, author James McBride pulls this off admirably by presenting the abolitionist John Brown -- a character who appeared as an awe-inspiring tactician in other books I've read recently (March and Gilead) -- as a raving, Bible-thumping, impulsive lunatic whose "cheese had slid off his biscuit". If this wasn't about a real person and historical events, The Good Lord Bird would still be an entertaining read, but as a way of bringing history to life, this is a compelling perspective. What I'm left with, however, is an uncomfortable sense that some issues (like slavery and those who would give their lives to fight it) just might be beyond satire.

The Good Lord Bird is told in a narrative style as the story of a 100+ year old former slave reminiscing about his years riding with Captain John Brown. After his father was accidentally killed, the young boy (dressed in a potato sack like all local slave children and possessing light skin, long curly hair, and delicate features) was liberated by Brown, who assumed he was a girl:

See, my true name is Henry Shackleford. But the Old Man heard Pa say “Henry ain’t a”, and took it to be “Henrietta.” Which is how the Old Man’s mind worked. Whatever he believed, he believed. It didn’t matter to him whether it was really true or not. He just changed the truth till it fit him. He was a real white man.This suited Henry (primarily known as Little Onion after he mistakenly ate Brown's lucky onion) since, as a girl, he wasn't expected to fight or work overly hard, and thusly "traveling incog-Negro", he had a front row seat to all of Brown's oddball ways. Brown himself was not an impressive looking figure:

He was a stooped, skinny feller, fresh off the prairie, smelling like buffalo dung, with a nervous twitch in his jaw and a chin full of ragged whiskers. His face had so many lines and wrinkles running between his mouth and eyes that if you bundled 'em up, you could make 'em a canal. His thin lips was pulled back to a permanent frown. His coat, vest, pants, and string tie looked like mice had chewed on every corner of 'em, and his boots was altogether done in. His toes stuck clean through the toe points.

And when the devout Calvinist got to praying (saying grace, asking for guidance, halting suddenly to receive direct messages from God), Brown would comically preachify for hours on end. The small militia that Brown led (mostly made up of his own sons) camped in the hills, scavenged food, and seemingly wandered aimlessly. As a result, Little Onion made many attempts to escape back to his former owner because, "Fact is, only time I was hungry and eating out of garbage barrels and sleeping out in the cold was when I was free with him." Eventually, Onion witnesses the Pottawatomie Massacre (which does not read as remotely justifiable), and not long after, he and another freed slave are captured by pro-slavery redshirts. The following (I know, too long a quote, but where could I end it?) conversation with the captors made me laugh (and gives a good sense of the writing style):

"Trim's my business," I said proudly, for I could cut hair.The redshirts sell the slaves to a whorehouse, where luckily, Little Onion is only expected to clean and serve in the saloon, but her companion Bob is put into the slave pen -- a fenced-in, mucky area in the yard with a small canvas for shelter where the saloon owner keeps her own slaves (who are rented out for daily labour) and where visitors to town can park their slaves for the day. This disgusting arrangement (new to me), contrasted with the better living conditions and social standing of the lighter-skinned house slaves, was very interesting, and for the most part, not played for laughs. Eventually, Brown and his sons find Little Onion and Bob, and after freeing them once again, Brown decided to bring the "girl" back East with him on a fund-raising campaign.

He perked up. "Trim?"

Now, having growed up with whores and squaws at Dutch's, I shoulda knowed what that word "trim" meant. But the truth is, I didn't.

"I sell the best trim a man can get. Can do two or three men in an hour."

"That many?"

"Surely."

"Ain't you a little young to be selling trim?"

"Why, I'm twelve, near as I can tell it, and can sell trims just as good as the next person," I said.

His manner changed altogether. He polited up, wiping his face clean with his neckerchief, fluffing his clothes, and straightening out his ragged shirt. "Wouldn't you rather have a job waiting or washing?"

"Why wash dishes when you can do ten men in an hour?"

Chase's face got ripe red. He reached in his sack and drawed out a whiskey bottle. He sipped it and passed it to Randy. "That must be some kind of record," he said. He looked me out the corner of his eye. "You want to do me one?"

"Out here? On the trail? It's better to be in a warm tavern, with a stove heating and cooking your victuals, while you enjoys a toot and a tear. Plus I can clip your toenails and soak your corns at the same time. Feet's my specialty."

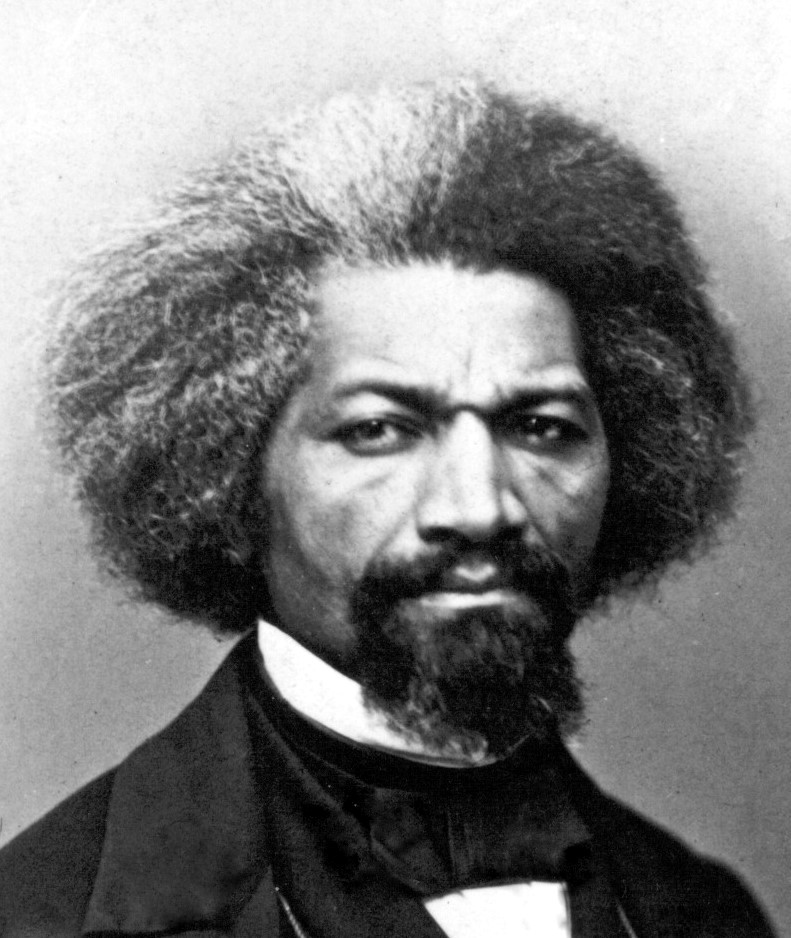

It is on this trip that they meet up with Frederick Douglass, and it's the mocking treatment of this iconic figure that makes me the most uncomfortable.

(E)very inch of movement in that house, every speck of cleaning, cooking, dusting, working, writing, pouring of lye, and sewing of undergarments revolved around Mr. Douglass, who walked about the house like a king in pantaloons and suspenders, practising his orations, his mane of dark hair almost as wide as the hallways, his voice booming down the halls.

It's said that Douglass is married to a white and a black woman at the same time (for which I can't find actual evidence even if there were rumours of inappropriate friendships), and although Douglass is said to have shunned tobacco and alcohol, in The Good Lord Bird he isn't averse to sharing a bottle or two of whisky with Little Onion in order to seduce the young girl.

Brown and Little Onion go on to Canada where they meet Harriet Tubman (the General to Captain Brown), and the plans for attacking Harper's Ferry begin to be unveiled. At this point -- with his detailed strategy, knowledge, and maps -- Brown loses his air of lunacy, and if only Little Onion had been better able to "hive the bees" (rally the local slaves to revolt), the history of the United States might have taken a different course. The raid itself is an exciting tale, and through to its ultimate (and generally known) conclusion, the farcical tone of the book is abandoned for a more serious one.

This is much more plot than I usually give, but this is a lot of story to evaluate. It seems that even in his lifetime, many people thought that John Brown was a dangerous fanatic, so his treatment in The Good Lord Bird seems defensible. The cross-dressing of Henry/Henrietta/Little Onion is played hard for laughs throughout, but as I remembered a similar event taking place in Uncle Tom's Cabin (when Eliza and her son both assume opposite genders to escape to Canada), I was conscious that this might have been an iconoclastic effort by author James McBride. But I'm still scratching my head over the treatment of Frederick Douglass; why make such a fool out of a heroic, historical figure? In this interview, McBride says:

Slavery is hard to talk about because we focus on the stereotypes and the brutality of the institution. We have to find ways to discuss the past while giving each other room to breathe, make mistakes, and stumble forward despite our lack of wisdom and knowledge on that subject. If that doesn’t happen, the conversation does not happen. If the conversation does not happen, the discourse dries up, the learning stops, and the ability to understand one another dissipates.In a world where The Daily Show is considered a trusted news source, I guess I can accept that an African-American author might choose to use satire to keep the discourse about slavery open; especially when The Good Lord Bird is a very well written book. I did laugh (uncomfortably sometimes), I did learn quite a bit (though, as with the two Mrs. Douglasses, I can't be 100% sure of the historical accuracy), and I cared about the characters -- and there's not much more that I can ask from a book.

Mallory bought me this book for Christmas, after seeking the advice of the woman at the book store. After describing the kinds of books I like and my favourite authors, the clerk told Mal that I would either love this book or hate it (she herself loved it) and Mal took the chance. And I'm glad she did -- I'd rather read something potentially controversial than a pop-fiction potboiler -- and I am very close to loving this book. I understand that making me uncomfortable might have been part of McBride's goal here, but it left me thinking of Dave Chappelle. They say that Chappelle left show business and moved to Africa (I believe he's come back now?) because one night, while performing, he looked out into the audience and saw nothing but trucker-hat-wearing, beer-bellied white guys laughing at him and he felt like a minstrel show (make us laugh Lil Sambo). Even as a Canadian who feels no personal connection to America's history of slavery and racial unrest -- even as I read this book alone, chuckling where no one could hear me -- I was conscious of my trucker hat and beer belly, not wanting to offend even in the abstract.

Also, while looking for a source to link to while referring to Jon Stewart as a "trusted news source", I also found this link; an excerpt from the recently published #Newsfail. Presumably written by people who are not fanatical conservatives (one of the authors was encamped with the Occupy Movement), I was gratified to see that they agreed with me that Jon Stewart has gone off the rails:

More than fifteen years after its debut on a network whose name should have given us a clue to the show’s true allegiance, “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart” (which premiered in 1999 after giving Craig Kilborn the old heave-ho as the original “Daily Show” host) has gone from an invaluable bullshit detector on a government waging unjust wars on a mad hunt for nonexistent weapons of mass destruction, to, at best, an armchair activist’s watercooler conversation starter (“Hey, did you hear what Jon Stewart said last night?” “Yeah, I feel like I know everything there is to know about the Middle East now. Want to hit up the falafel cart for lunch?”) and at worst, a “news” program that’s as guilty of cheerleading some of President Obama’s worst offenses as Fox “News” was of rooting for Dubya’s never-ending wars.That's exactly my beef: Stewart was doing a wonderful public service while exposing the problems in the Bush administration (in a way that real news outlets couldn't), but being such a partisan, he now spends his time defending rather than exposing problems in Obama's. And that's a problem when young people are looking to The Daily Show as their news source. And again I wonder: is it the cultural grooming of TV shows like this that make an author want to take a less-than-serious look at a very serious topic? Is that the only way that McBride could have seen to engage a modern audience in a discussion of slavery? Or is this just the writing sensibility of an Oberlin College graduate who now teaches at Columbia, like fellow absurdist Gary Shteyngart?

And the fact that these questions are under my skin is, to me, the mark of fine literature -- good find, Mallory!