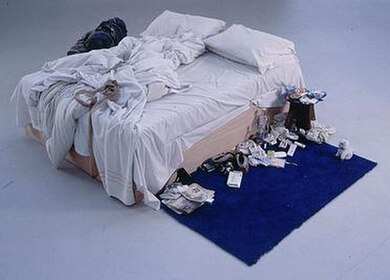

My Bed is an art piece that was exhibited at the Tate Gallery in 1999 and was shortlisted for the Turner Prize. Created by Tracey Emin, the installation consisted of the artist's own bed, unmade since she had lain in it suffering from suicidal depression for several days in 1998, with some messy piles of garbage and dirty clothes at bedside. This piece was auctioned in the summer of 2014 for £2.2 million. Obviously, there are people who consider a person's unmade bed and stained knickers to be art and if I were to point and declaim, "The Emperor has no clothes!", I'm certain the arbiters of culture would reply, "No, as it turns out, the weavers actually were able to make a cloth only visible to the wise, and you have failed the test". So too, as I look at the glowing reviews for Siri Hustvedt's The Blazing World, I feel like I have somehow failed the test.

|

| My Bed |

The construction is promising: The book begins with an Editor's Note that explains who Harriet Burden was (a frustrated artist) and the great experiment that she pulled off (to mount three art shows under the names of three different men, to see if the artist's gender did affect her art's reception). The editor I. V. Hess (of unknown gender, but from what Hustvedt has said in interviews, can be considered an avatar of the author herself) then compiled excerpts from Burden's journals, interviews with people who knew her, essays from Burden's children, and quotes from art journals. The picture of Burden that emerges is of a voracious reader of challenging and eclectic tastes who, although in possession of potent artistic skills, has allowed herself to be pulled into the roles of wife and mother, to the neglect of her own art. Once Burden's husband dies, she is free to concentrate on her art and conceives of Maskings: the three art shows that take 15 years to complete, and that, with her eventual unveiling of the truth and all criticism, sales data, and other related "peripherals", would eventually make one cohesive work of art. As Burden wrote, "It was meant not only to expose the antifemale bias of the art world, but to uncover the complex workings of human perception and how unconscious ideas about gender, race, and celebrity influence a viewer’s understanding of a given work of art." So far, so good.

In the journals, Harriet "Harry" Burden reveals herself to be a deep thinker, concerned with the interplay of neuroscience, phenomenology, psychoanalysis, philosophy, literature and art. She quotes Spinoza, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, and especially her personal hero, Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (a long-dead fellow female artist who railed against chauvinism in her lifetime and didn't receive respect until after her death). There are a lot of dense philosophical and scientific passages, and uncited references and wordplays are explained in footnotes (which is, of course, just one more layer of clever as it's Hustvedt who must both employ and then explain the usages). And it doesn't take much biographical detective work to learn that Burden's passions are Hustvedt's own and that Hustvedt must have artist-gender issues of her own as she is married to the wider-read Paul Auster.

And so, on top of the esoteric bits, the art works that are created further distanced me from Burden -- they are increasingly complex and multi-media, with the participation and reactions of the viewers an integral part of the art, and like with My Bed , I am enough of a Philistine to wonder, "Who could buy this? Where would they put it?" (And I had the same reaction last year while reading The Woman Upstairs.) But I do understand the complexity of the art described, and although not actually constructed, Hustvedt has certainly created three major art installations here and I can't help but wonder, "How would they be received if they were constructed? Pretentious and naïve, as Burden's early works were dismissively described? Or as works of genius, perhaps even, on par with an unmade bed?"

There was so much clever-clever stuff in this book that I'm certain I only recognised a small fraction of it (although much is overt like: Harriet "Harry" Burden = hairy burden = gender-specific body as encumbrance) and found the Richard Brickman letter to be mindbending: When it came time for Burden to unveil herself, she chose to write a letter to an obscure art journal, claiming to be a man named Richard Brickman (he turns out to be Burden's invention) who had received a 60+ page meandering rant of a letter from Harriet Burden, in which she claimed to be the artist behind the three art installations. Brickman declares not to understand much of what Burden tries to say, and in a passage not atypical of this book, says:

Her letter escorts the reader on a convoluted path from Homer to the Stoics to Vico, leaping forward to W. T. H. Myer's subliminal self, to Janet, Freud, and James, to Edmund Husserl's phenomenology of time consciousness and intersubjectivity and then to contemporary infant research, as well as neuroscience findings about primordial selves, and locationist hypotheses which focus on the hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray areas of the brain, as well as a Finnish Scholar Pauli Pylkkö, who advances a notion of "aconceptual mind", and an obscure novelist and essayist, Siri Hustvedt, whose position Burden calls "a moving target". As far as I can tell, Burden attempts to undermine all conceptual borders, which, I believe, define human experience itself. I cannot say that her wild romp into the more peculiar aspects of continental philosophy convinced me. The woman flirts with the irrational.Get it? Burden writes a letter, as a fictional man, that dismisses much of what Burden believes as flirting "with the irrational" and namedrops the actual author, Hustvedt, in an unflattering way. A few pages later, the editor (whom we should consider to be Hustvedt) explains the letter thus: She wanted everyone to understand how complicated perception is, that there is no objective way of seeing anything. Brickman became another character in the larger artwork, another mask, this time textual, which is part of a philosophical comedy, if you will. Get it? I don't know if I do. For all that I value my own gifts of perception, I'm left feeling like I'm the one exposed as wearing no clothes; like my hairy burden and I are the butt of this philosophical comedy.

And yet this book…The characters were mostly very strong and Burden was a sympathetic protagonist -- the reader wants her to succeed and setbacks are distressing. The density of the journals are offset by more straightforward reporting in the other sections (and it is reporting; this isn't lovely prosy writing, and of course, not meant to be). The eventual revealing of Burden's whole life and career (and especially her relationship with the third male artist, Rune) was a satisfying mystery unravelled. The treatment of women artists is explored without resorting to feminist-victimisation language (there is a section on how the male brain -- and its development of spatial areas -- might simply create stronger artists and a section in which Burden explains how trying to create art behind the mask of a man seemed to have tapped a different -- and perhaps more powerful -- well of inspiration). There are so many reasons to like this book, and while I admire the construction of all the meta-bits (this may well be a work of genius), I'm left feeling manipulated; like as though if I said, "The Emperor has no clothes!", the arbiters of culture would just sadly shake their heads at me and walk away; not even worth their time to bother educating. I'm going to wimp out and give it a middling three stars and leave on one last note: It should be pointed out that the celebrated artist behind My Bed is, indeed, a woman. But does that mean anything?

I read this book because it is on the Man Booker longlist, and again, I'm just annoyed with this year's selections. To what degree did the jury choose the titles based on their gimmick of "alternate forms of storytelling" this year? The shortlist comes out today and I've only read three of the books so far, so maybe I'll be spared more books that will just annoy me.

That said, I would be interested in reading more of Siri Hustvedt, and discovering new authors is always my aim with the Booker.

Man Booker Prize Shortlist 2014:

J by Howard Jacobson

I've only read one of those, am on the waiting list for the rest, so don't expect to get to them all before the winner is revealed next month. Rats.