Knowledgeable reviewers liken the format of The Buddha in the Attic to the Japanese art of sumi-e -- sparse swabs of black ink on white ricepaper that showcase light and shadow and highlight the void -- but I can no more compare a book to a style of painting than I can compare one to bonsai pruning or tea ceremonies; as I can only compare a book to my own entirely subjective history of reading other books, I must confess that the format here, while indeed highlighting the void, left me wanting.

The Buddha in the Attic begins with a boatload of "picture brides" -- young Japanese women in the early 1900s who agreed to marriage proposals based on pictures of their would-be husbands in America -- and immediately the first person plural format is employed:

On the boat we were mostly virgins. We had long black hair and flat wide feet and we were not very tall. Some of us had not eaten anything but rice gruel as young girls and had slightly bowed legs, and some of us were only fourteen years old and were still young girls ourselves. Some of us came from the city, and wore stylish city clothes, but many more of us came from the country and on the boat we wore the same old kimonos we'd been wearing for years -- faded hand-me-downs from our sisters that had been patched and redyed many times.This is the format for the whole book: there are no individual characters, and this did and didn't work for me. By listing a wide variety of circumstances and experiences, while grouping them together in eight chapters that describe the eventual milestones in the lives of all the picture brides, the reader never gets to know any one of them personally, yet is able to appreciate the overall pattern. The first shock comes for the brides as soon as they arrived:

On the boat we could not have known that when we first saw our husbands we would have no idea who they were. That the crowd of men in knit caps and shabby black coats waiting for us down below on the dock would bear no resemblance to the handsome young men in the photographs. That the photographs we had been sent were 20 years old. That the letters had been written to us by people other than our husbands, professional people with beautiful handwriting whose job it was to tell lies and win hearts. That when we first heard our names being called out across the water one of us would cover her eyes and turn away — I want to go home — but the rest of us would lower our heads and smooth down the skirts of our kimonos and walk down the gangplank and step out into the still warm day. This is America, we would say to ourselves, there is no need to worry. And we would be wrong.The brides experienced their first night:

That night our new husbands took us quickly. They took us calmly. They took us gently, but firmly, and without saying a word. They assumed we were the virgins the matchmakers had promised them we were and they took us with exquisite care. Now let me know if it hurts. They took us flat on our backs on the bare floor of the Minute Motel. They took us downtown, in second-rate rooms at the Kumamoto Inn. They took us in the best hotels in San Francisco that a yellow man could set foot in at the time. The Kinokuniya Hotel. The Mikado. The Hotel Ogawa. They took us for granted and assumed we would do for them whatever it was we were told… They took us as we stared up blankly at the ceiling and waited for it to be over, not realizing that it would not be over for years.They began to work in the fields alongside their new husbands as itinerant farm labourers (despite having been promised rescue from a similar fate in the rice paddies of Japan had they stayed), sleeping at night in tents and barns and chicken coops. They had children (or suffered childlessness), bought businesses or farms of their own, raised their families, and more than anything, tried to maintain their culture and keep out of the way of the large and loud Americans. When Pearl Harbor was bombed, they regretted not having tried harder to fit in -- we made them hate us -- and gathered compliantly when they were told they were being shipped away by Presidential order.

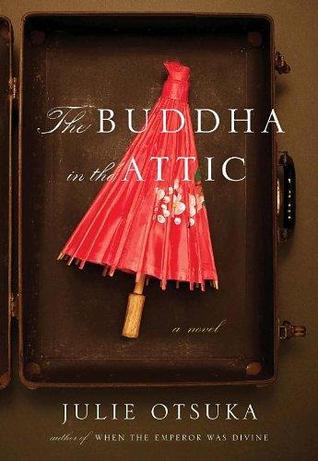

I assumed that these people's story would end in the War Relocation Camps -- and was looking forward to it -- so was disappointed when the final section was from the point of view of the Americans who barely noticed that their Japanese neighbours has disappeared. I see now that Julie Otsuka covered the internment camp experience in her earlier novel When the Emperor Was Divine, but I'm iffy about looking for it.

I listened to this on audiobook, and that may have been a mistake: as experiences were listed with very little exposition, I often found my mind wandering, and when I would snap back to attention, it was just more of the same. I understand that's kind of the point -- and this book won the PEN/Faulkner, so knowledgeable people must have gotten more out of it than I did -- but The Buddha in the Attic was not my favourite.