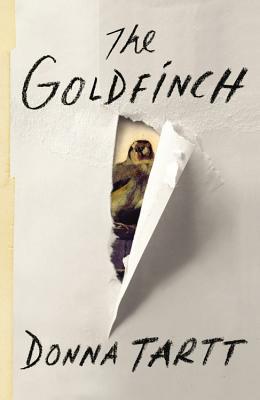

If a painting really works down in your heart and changes the way you see, and think, and feel, you don't think, 'oh, I love this picture because it's universal.' 'I love this painting because it speaks to all mankind.' That's not the reason anyone loves a piece of art. It's a secret whisper from an alleyway. Psst, you. Hey kid. Yes, you...You see one painting, I see another…it'll never strike anybody the same way and the great majority of people it'll never strike in any deep way at all but -- a really great painting is fluid enough to work its way into the mind and heart through all kinds of different angles, in ways that are unique and very particular. Yours, yours. I was painted for you.I'm starting with this meditation on the nature of art because I believe that it's the whole point of my reaction to The Goldfinch -- this book did work its way into my mind and heart, and judging from other readers' reviews, that isn't a universal experience, and that has to be okay: I reckon it isn't expected to be.

I am glad that I actually, physically, read this book because, although I have heard that the audio version is pretty good, I found the punctuation to be so purposeful and artful that it served its own role; that of the brushstrokes and paint layering and structural choices found in the eponymous painting itself. An example (random and perhaps not perfectly illustrative of my point):

Delivery boys from D'Agostino's and Gristede's pushed carts laden with groceries; harried executive women in heels plunged down the sidewalk, dragging reluctant kindergarteners behind them; a uniformed worker swept debris from the gutter into a dustpan on a stick; lawyers and stockbrokers held their palms out and knit their brows as they looked up at the sky. As we jolted up the avenue (my mother looking miserable, clutching at the armrest to brace herself) I stared out the window at the dyspeptic workaday faces (worried-looking people in raincoats, milling in grim throngs at the crosswalks, people drinking coffee from cardboard cups and talking on cell phones and glancing furtively from side to side) and tried hard not to think of all the unpleasant fates that might be about to befall me: some of them involving juvenile court, or jail.At the risk of sounding all Strunk & White fangirl, the punctuation in that passage delights me as much as the visuals it paints -- the semicolons and parenthesis, and then that final colon -- it may only be speaking to me, but these are masterstrokes to my eye. I know there are complaints about the long summing-up paragraphs at the end of this book, but the fact that some bits are in square brackets totally redeems them to me (nerdly, I know). This was such a visual book, but again, I understand if I am in a minority of readers who valued the craft as much as the plot. In the end, it's analogous to the fact that this work affects me:

While this does not:

Both are considered masterpieces, yet they don't speak to me -- personally -- equally. And The Goldfinch affected me in such a strange and personal way -- I was anxious and disturbed throughout much of the book; and not just because I was worried about the fates of the characters (and especially Theo) and the painting. What I found most disturbing was the way that so many characters refused to answer questions that were put to them: from Theo not responding to the investigators and counsellors he first meets; to Boris showing up and not answering any questions about where he's taking Theo and why; to Kitsey refusing to respond to the accusations Theo levels at her. This was a peculiar level of tension that Donna Tartt maintained -- periodically reminding me of -- over the course of a long book, and in my reading experience, I am grateful to any book that provokes an emotional reaction from me -- whether positive or negative. And of course most of my feelings were negative: I would agree that most of the characters are unlikeable, and anyone who would call this story Dickensian would be forgetting the fact that orphans in Dickens novels tend to be plucky urchins who fight against and overcome unfairness and adversity while Theo succumbs to and wallows in his tragedies.

And, sure, there was an unevenness to the plot -- I really enjoyed the beginning part in NYC (even forgiving logical lapses like how Theo escaped the museum -- with the painting -- undetected) and found the initial part of the section in Las Vegas, with Boris, to be amazing. In a review for The New York Times, Stephen King wrote, "Tartt depicts the friendship of these two cast-adrift adolescent boys with a clarity of observation I would have thought next to impossible for a writer who was never part of that closed male world: the interminable talk and speculation, the endless TV watching and pizza eating, the dope smoking and small thefts, the kind of rapport in which a single cocked eyebrow can provoke howls of helpless laughter." But it went on for too long, in my opinion; too much of the same with the drugs and the movies and the stolen candy for dinner. And I didn't love Theo's new life in New York (after the initial reunion with Hobie, which I did like) but it picked up again when Boris drops back into the scene. Over all, this book was probably too long; the subject matter not requiring an epic (even if it took 12 years to write, and one assumes, had much edited out as it was).

But that's the big picture -- the painting viewed from a distance -- that doesn't appreciate the small strokes that can only be seen from up close. I appreciated this bit as it sums up my own worldview:

And as much as I’d like to believe there’s a truth beyond illusion, I’ve come to believe that there’s no truth beyond illusion. Because, between ‘reality’ on the one hand, and the point where the mind strikes reality, there’s a middle zone, a rainbow edge where beauty comes into being, where two very different surfaces mingle and blur to provide what life does not: and this is the space where all art exists, and all magic. And—I would argue as well—all love.And these moments of irony stuck out to me:

"People die, sure,” my mother was saying. “But it’s so heartbreaking and unnecessary how we lose things. From pure carelessness. Fires, wars. The Parthenon, used as a munitions storehouse. I guess that anything we manage to save from history is a miracle."And:

There had been nights in the desert where I was so sick with laughter, convulsed and doubled over with aching stomach for hours on end, I would happily have thrown myself in front of a car to make it stop.And to those who would complain that there is too much irony in The Goldfinch -- too many Dickensian coincidences to make it believable -- Tartt makes a pre-emptive response: After Boris explains why all of the coincidences may point to the steering hand of God or fate, Theo says, "I think this goes more to the idea of 'relentless irony' than 'divine providence.' " Boris replies, "Yes -- but why give it a name? Can't they both be the same thing?" Well, can't they? Another point that Tartt made in this book:

That life — whatever else it is — is short. That fate is cruel but maybe not random. That Nature (meaning Death) always wins but that doesn’t mean we have to bow and grovel to it. That maybe even if we’re not always so glad to be here, it’s our task to immerse ourselves anyway: wade straight through it, right through the cesspool, while keeping eyes and hearts open. And in the midst of our dying, as we rise from the organic and sink back ignominiously into the organic, it is a glory and a privilege to love what Death doesn’t touch.Tartt was swinging for the fences in writing The Goldfinch; attempting to create art; the appreciation of which is always a subjective experience. It worked for me, may not work for you, but as always, I admire those who try to transcend and make something that "Death doesn't touch".